Everything in the universe is the fruit of chance or necessity.

DEMOCRITUS, c.460370 B.C.

PREFACE

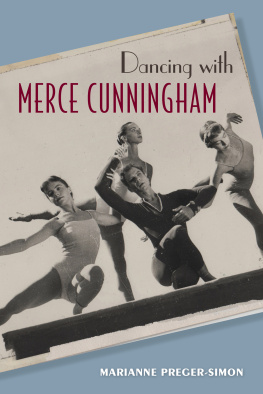

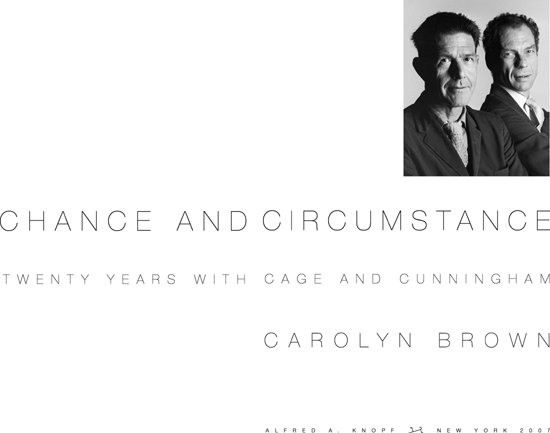

O ne day, a year or two after Id stopped performing with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, I received a phone call from Maxine Groffsky, who had left her position as the Paris editor of the Paris Review and had returned to New York. I want to be your agent? she said. Astonished, I asked, For what? Your book. What book The one John Cage says youre going to write. Well, maybe, someday. No, now. I resisted; she persisted. So I wrote a sample chapter and Maxine presented it to Bob Gottlieb, then editor in chief at Knopf, and suddenly I found myself committed to the daunting project of writing a book. That was over thirty years ago. The writing and the not writing took that long.

The book chronicles a twenty-year period in the life of the company based on voluminous journals and lettersadmittedly self-referential that Id written during that time. It is just one version of the story, but surely there are as many other versions as there were people involved plus that impossible, truly objective one.

With rare exception, books Ive readdescribing events Ive experienced firsthandhave had factual errors. No doubt there will be errors here as well, but facts are not the essence of this book so much as feeling.

1 BEGINNINGS

T he taxi moved slowly along the rue du Bac and across the Pont Royal. Hazy, late morning sunlight filtered through the remaining chestnut leaves, spilling on damp cobblestones and the darkly glinting waters of the Seine. Paris. Autumn. October 29, to be exact, a Sunday, with scarcely another automobile on the boulevard, and only an occasional pedestrian walking by the river. I held hard the hand of my friend Jim Klosty in the hope that it would relieve the knot thickening in my throat and quiet the fear that I wouldnt be able to control the excess of feeling that had been steadily mounting since the first day of our weeklong run at the Thtre de la Ville. For the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, this day, with a matinee performance, was the end of the Paris season and the end of the 1972 tour begun in Iran in early September. For me, it was the end of a twenty-year way of life.

I had deliberately chosen to end that life abruptly, telling no one but those most intimately concerned, and to end it where I loved performing mostin Europe. A romantic gesture, certainly, but one that insured a happy ending to a life I cherished and had been nourished by. Most of all, I wanted to leave well. Only one of Merces dancers had managed that in the past: Marianne Preger. With grace and good humor and abundant love, she managed to depart the company, having chosen motherhood and family after more than eight years dancing with Merce. Without feeling rejected, Merce was able to accept her decision. Like Marianne, I wanted to leave without ill feeling, rancor, or bitterness. I believe I managed it, though certainly not without pain on both sides. One cannot leave, after dancing in the company of Merce Cunningham and John Cage for any number of years, without suffering enormous loss. A loss never to be retrieved. But I knew, and had known for several years, that I needed to move on; perhaps what is surprising is that I stayed so long.

It was shortly after graduating from Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, marrying Earle Brown, my childhood sweetheart, and moving to Denver, Colorado, that I first saw Merce Cunningham dancenot perform, I hasten to add, but dance, in a master class that he taught and I took in April 1951. He was slender and tall, with a long spine, long neck, and sloping shoulders; a bit pigeon-breasted. There was a lightness of the upper body which contrasted with the solid legs, so beautifully shaped, and the heavy, massive feet. The body was a blue-period Picasso saltimbanque, though the face and head were not. I remember Merce most clearly demonstrating a fall that began with him rising onto three-quarter point in parallel position, swiftly arching back like a bow as he raised his left arm overhead and sinking quietly to the floor on his left hand, curving his body over his knees, rising on his knees to fall flat out like a priest at the foot of the cross, rolling over quickly and arriving on his feet again in parallel positionall done with such speed and elegance, suppressed passion and catlike stealth that my imitative dancers mind was caught short. I could not repeat it. I could only marvel at what I hadnt really seen. His dancing was airborne then; critics and audiences of that time still cannot forget his extraordinary gift for jumping. An Aries, born April 16, 1919, about one month before and in the same year as Margot Fonteyn, Merce Cunningham had an appetite for dancing that seemed to me then, as it does today, to be his sole reason for living.

I was brought up on dancing; for fourteen years or more my mother, Marion Stevens Rice, had taken me to dance events in Bostonballet, modern, ethnic. Id watched her take class from Ted Shawn and members of the Braggiotti Denishawn school, caught glimpses of Miss Ruth (Ruth St. Denis) through open studio doors, sat mesmerized in a box in the old Boston Opera House for scores of performances of Ballets Russes and later Ballet Theatre, and each summer we went faithfully to Ted Shawns Jacobs Pillow for every new program. Despite that exposure, Id never seen anyone move like Merce: he was a strange, disturbing mixture of Greek god, panther, and madman.

But seeing Merce move and experiencing vicariously his hungry passion for dancing in the two classes he taught was not a reason to pack up, leave Denver, and follow him back to New York. It would never have occurred to me to do that. I had no intention of becoming a dancer. Born to a dancing mother, having danced since I was three, I had rejected life as a dancer or dancing teacher. I wanted to write, and with that in mind, I went off to college for four years to major in philosophy, taking no tights or leotards, convinced that my dancing days were over. My mother said nothing, but she admits to an I knew it! smile at my frantic letter two weeks later requesting my practice clothes by return mail. I danced and choreographed all four years at college, but refused to write my honors thesis on dance aesthetics as my philosophy professor Holcombe Austin suggested. Dance wasnt serious enough. I needed a reasona philosophical raison dtrefor a life in dance to which to devote myself. It was John Cage who provided that, though I didnt realize it at the time.

John and Merce were on a tour of the United States. Just the two of them. John performed his Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano In Denver, where he taught the Schillinger System of arranging and composition, Earle found no one to talk with except his students, most of them jazz musicians (Broadway and Hollywood composers had been prominent among Schillingers students), and Eric Johnson, a young pianist-composer who accompanied dancers and composed for Jane McLean. It was Jane who had arranged for Cunningham and Cage to appear in Denver, although she could not afford to present them in a dance concert, and it was Jane (a dancer formerly with Martha Graham and thereby an acquaintance of Merce) with whom I was then studying and performing. Johnson, her pianist, had met John Cage in New York and reported back to us that John was charming but completely crazy, a common consensus in those years. Charming John Cage most certainly could be; completely crazy he was not, had never been.