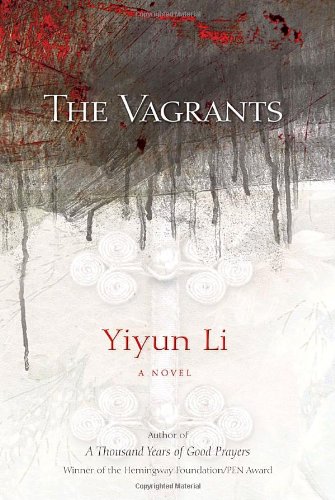

Yiyun Li - The Vagrants

Here you can read online Yiyun Li - The Vagrants full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Random House, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Vagrants

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Vagrants: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Vagrants" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Vagrants — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Vagrants" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

A Thousand Years of Good Prayers

For my parents

T he mass and majesty of this world, all

That carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help and no help came:

What their foes liked to do was done, their shame

Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died.

W. H. AUDEN, THE SHIELD OF ACHILLES

T he day started before sunrise, on March 21, 1979, when Teacher Gu woke up and found his wife sobbing quietly into her blanket. A day of equality it was, or so it had occurred to Teacher Gu many times when he had pondered the date, the spring equinox, and again the thought came to him: Their daughters life would end on this day, when neither the sun nor its shadow reigned. A day later the sun would come closer to her and to the others on this side of the world, imperceptible perhaps to dull human eyes at first, but birds and worms and trees and rivers would sense the change in the air, and they would make it their responsibility to manifest the changing of seasons. How many miles of river melting and how many trees of blossoms blooming would it take for the season to be called spring? But such naming must mean little to the rivers and flowers, when they repeat their rhythms with faithfulness and indifference. The date set for his daughter to die was as arbitrary as her crime, determined by the court, of being an unrepentant counterrevolutionary; only the unwise would look for significance in a random date. Teacher Gu willed his body to stay still and hoped his wife would soon realize that he was awake.

She continued to cry. After a moment, he got out of bed and turned on the only light in the bedroom, an aging 10-watt bulb. A red plastic clothesline ran from one end of the bedroom to the other; the laundry his wife had hung up the night before was damp and cold, and the clothesline sagged from the weight. The fire had died in the small stove in a corner of the room. Teacher Gu thought of adding coal to the stove himself, and then decided against it. His wife, on any other day, would be the one to revive the fire. He would leave the stove for her to tend.

From the clothesline he retrieved a handkerchief, white, with printed red Chinese charactersa slogan demanding absolute loyalty to the Communist Party from every citizenand laid it on her pillow. Everybody dies, he said.

Mrs. Gu pressed the handkerchief to her eyes. Soon the wet stains expanded, turning the slogan crimson.

Think of today as the day we pay everything off, Teacher Gu said. The whole debt.

What debt? What do we owe? his wife demanded, and he winced at the unfamiliar shrillness in her voice. What are we owed?

He had no intention of arguing with her, nor had he answers to her questions. He quietly dressed and moved to the front room, leaving the bedroom door ajar.

The front room, which served as kitchen and dining room, as well as their daughter Shans bedroom before her arrest, was half the size of the bedroom and cluttered with decades of accumulations. A few jars, once used annually to make Shans favorite pickles, sat empty and dusty on top of one another in a corner. Next to the jars was a cardboard box in which Teacher Gu and Mrs. Gu kept their two hens, as much for companionship as for the few eggs they laid. Upon hearing Teacher Gus steps, the hens stirred, but he ignored them. He put on his old sheepskin coat, and before leaving the house, he tore a sheet bearing the date of the previous day off the calendar, a habit he had maintained for decades. Even in the unlit room, the date, March 21, 1979, and the small characters underneath, Spring Equinox, stood out. He tore the second sheet off too and squeezed the two thin squares of paper into a ball. He himself was breaking a ritual now, but there was no point in pretending that this was a day like any other.

Teacher Gu walked to the public outhouse at the end of the alley. On normal days his wife would trail behind him. They were a couple of habit, their morning routine unchanged for the past ten years. The alarm went off at six oclock and they would get up at once. When they returned from the outhouse, they would take turns washing at the sink, she pumping the water out for both of them, neither speaking.

A few steps away from the house, Teacher Gu spotted a white sheet with a huge red check marked across it, pasted on the wall of the row houses, and he knew that it carried the message of his daughters death. Apart from the lone streetlamp at the far end of the alley and a few dim morning stars, it was dark. Teacher Gu walked closer, and saw that the characters in the announcement were written in the ancient Li-styled calligraphy, each stroke carrying extra weight, as if the writer had been used to such a task, spelling out someones imminent death with unhurried elegance. Teacher Gu imagined the name belonging to a stranger, whose sin was not of the mind, but a physical one. He could then, out of the habit of an intellectual, ignore the grimness of the crimea rape, a murder, a robbery, or any misdeed against innocent soulsand appreciate the calligraphy for its aesthetic merit, but the name was none other than the one he had chosen for his daughter, Gu Shan.

Teacher Gu had long ago ceased to understand the person bearing that name. He and his wife had been timid, law-abiding citizens all their lives. Since the age of fourteen, Shan had been wild with passions he could not grasp, first a fanatic believer in Chairman Mao and his Cultural Revolution, and later an adamant nonbeliever and a harsh critic of her generations revolutionary zeal. In ancient tales she could have been one of those divine creatures who borrow their mothers wombs to enter the mortal world and make a name for themselves, as a heroine or a devil, depending on the intention of the heavenly powers. Teacher Gu and his wife could have been her parents for as long as she needed them to nurture her. But even in those old tales, the parents, bereft when their children left them for some destined calling, ended up heartbroken, flesh-and-blood humans as they were, unable to envision a life larger than their own.

Teacher Gu heard the creak of a gate down the alley, and he hurried to leave before he was caught weeping in front of the announcement. His daughter was a counterrevolutionary, and it was a perilous situation for anyone, her parents included, to be seen shedding tears over her looming death.

When Teacher Gu returned home, he found his wife rummaging in an old trunk. A few young girls outfits, the ones that she had been unwilling to sell to secondhand stores when Shan had outgrown them, were laid out on the unmade bed. Soon more were added to the pile, blouses and trousers, a few pairs of nylon socks, some belonging to Shan before her arrest but most of them her mothers. We havent bought her any new clothes for ten years, his wife explained to him in a calm voice, folding a woolen Mao jacket and a pair of matching trousers that Mrs. Gu wore only for holidays and special occasions. Well have to make do with mine.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Vagrants»

Look at similar books to The Vagrants. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Vagrants and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.