EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, SCD

PROF. RICHARD WEST, SCD, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT

PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

Contents

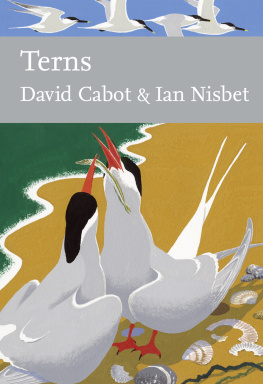

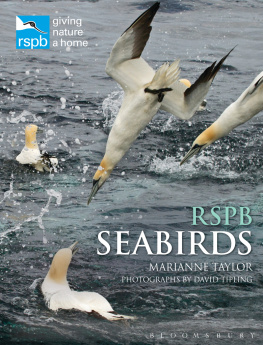

I T WOULD BE A SADLY SOMBRE NATURALIST on a summer seaside visit who failed to find the terns flying and feeding close inshore both strikingly beautiful and to a degree spiritually uplifting. Few would challenge the view that amongst seabirds in general they are the most elegant and easiest on the eye. Usefully, terns have a characteristic shape and, with subtle differences between species, flight patterns that ease identification for novices.

As a family, the terns have a truly global distribution, mostly associated with tropical or subtropical waters either during the breeding season or as their winter quarters after migration. David Cabot and Ian Nisbet deal with the true terns with 39 species worldwide, outlining in comparative terms their general lifestyle before focusing in detail on the five species that come each summer to breed beside British and Irish coastal seas and estuaries and, occasionally, on inland fresh waters, comparing their varied habits, habitats and migration.

Migration is an essential part of the tern way of life, much of which is spent on the wing, and some species make prodigious journeys. The Arctic tern is sometimes cited as the bird that sees more daylight than any other, breeding as it often does well to the north of the Arctic Circle. Here it enjoys a north polar summer of near-perpetual daylight, before migrating south across the Equator to the again near-perpetual daylight of the south polar summer in the Antarctic Ocean. Conservatively, an individual Arctic tern may cover in excess of 40,000 km each year, and with a life span that may exceed three decades, the potential lifetime distance travelled reaches staggering proportions. And these birds weigh little more than a garden blackbird!

Such enormous travels are inevitably accompanied by a range of natural hazards, and it is sobering to read of the threats terns face throughout their lives, at sea or on land. David Cabot in his Foreword notes that most British and Irish terns today are on life-support systems under intensive management schemes and protection from an array of natural and man-made problems. A chapter is devoted to these problems in detail, the measures being taken to counteract them and the additional research and measures that in the authors view are needed to avoid the possibility of several species ending up on the endangered list.

David Cabot and Ian Nisbet are both world-respected experts on terns, and bring between them a total of more than 75 years of study and experience on both sides of the Atlantic. Their coming together in 1991 was the result of serendipity: the arrival at a colony of roseate terns on the eastern seaboard of the USA (studied by Ian Nisbet) of a roseate tern ringed as a nestling two years earlier at a similar study colony (of David Cabots) near Dublin in Ireland. Their collective detailed knowledge and intimate familiarity with the terns radiate warmly from the text. Together, in New Naturalist 123 Terns, they have produced a thoroughly researched, detailed yet highly readable account of the biology and ecology of a group of well-known and well-loved seabirds, a worthy addition to any New Naturalist bookshelf.

A MONG MY EARLY MEMORIES is the rasping kirrick of Sandwich terns as they cruised along south Devon beaches where we played and swam, but my first serious encounters with terns came some years later, lying on my belly behind the breakwater at the tip of Dawlish Warren. There I watched hordes of migrating waders, pushed up towards the sea wall by the tide, and amongst them Sandwich, common, roseate and the occasional little tern, dribbling through on autumn migration. I wrestled with the complexities of identification, and the terns intrigued me where had they come from, where were they going? I knew a little about their legendary migrations, less about their breeding biology, and least of all about their behaviour or the many factors that ruled their lives. Little did I know then that I would later devote many years to studying the roseate tern, one of the most beautiful and intriguing of all our breeding birds.

The romance of studying terns is that apart from their inherent aesthetic attraction and biological interest, most of our terns nest in remote, wild and generally unspoilt areas, places that naturalists relish visiting. Arctic, roseate and Sandwich terns, in particular, have taken me to some stunningly beautiful places. The common tern by contrast is much less fussy about where it locates itself, and is often found nesting in noisy docklands, on roof tops, or in regimented nesting boxes on specially constructed floating platforms in flooded gravel pits or other inland waters.

I moved to Ireland in 1959, to a country with remarkably few experienced ornithologists, where even basic survey work in the more remote areas had the potential to make a major contribution. Initially I focused on establishing the locations of roseate tern colonies, and on censusing and monitoring. At that time relatively few roseate terns had been ringed, and I concentrated on ringing all available chicks. At one stage I had ringed approximately one-third of all chicks ringed in Britain and Ireland. These efforts were both fortuitous and rewarding because they coincided with the dramatic crash of the roseate tern population breeding in northwestern Europe during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The unusually high recovery rate of many of these ringed birds from West Africa during the population crash helped towards a better understanding of mortality pressures exerted on the terns wintering there.

In 1965 I attended the NATO conference on pesticides at Monks Wood. I already had an interest in pesticide residues and their possible impact on seabirds, and the conference stimulated me to investigate pesticide residue levels in the eggs and food of terns, especially roseates. Norman Moore arranged analyses of eggs and fish at the laboratory of the British government chemist while Jan Koeman in the Netherlands also carried out analyses. Later Colin Walker provided additional analytical services. This was all at a time when research on pesticide residues in birds was in its early stages. It was fortunate therefore that we were able to establish baseline organochlorine levels in our terns and their food.

Later work involved measuring the productivity of roseates, using methods derived from Ians work in the USA, at Ladys Island Lake and later at Tern Island, Wexford Harbour. Observations of food brought to chicks were made, together with notes on general tern behaviour. I also thought that it would be worth visiting the roseate tern colonies in Brittany, as the population there had also crashed but there was a paucity of data available. So Karl Partridge and I surveyed all possible roseate breeding sites in 1976 with the assistance of Yves Brien and J.-Y. Monat, supported by small grants from the French CNRS and the Irish National Science Council. The following year I made a limited follow-up survey.