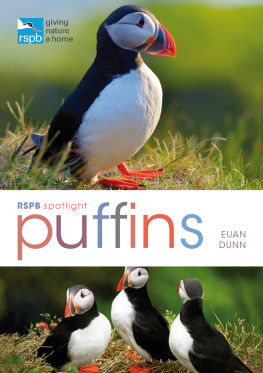

The RSPB is the countrys largest nature conservation charity, inspiring everyone to give nature a home so that birds and wildlife can thrive again.

By buying this book you are helping to fund The RSPBs conservation work.

If you would like to know more about the RSPB, visit the website at www.rspb.org.uk, write to The RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, or call 01767 680551.

First published in 2014

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

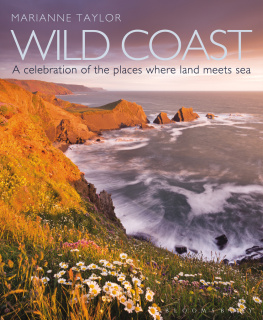

Copyright 2014 text Marianne Taylor

Copyright 2014 photographs David Tipling except as

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the

Publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. For legal purposes the constitute an extension of the copyright page.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

UK ISBN (hardback) 978-1-4729-0901-5

UK ISBN (ePUB) 978-1-4729-1116-2

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here .

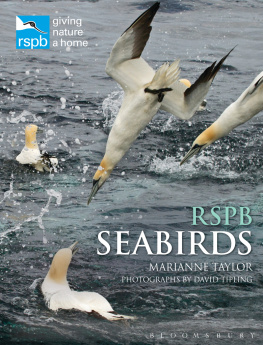

Kittiwakes. Photograph by David Tipling

Contents

Every summer, our sea cliffs play host to some of the most important seabird colonies in the world.

Introduction

Imagine sitting in a small boat on calm water. Masses of Gannets wheel overhead, huge and angelic, treading air with hardly a flicker of their white, black-tipped wings. As you watch one, it tilts downwards, folds in those long wings and, drawing them right back to turn itself into a spear, dives in a headlong, high-speed vertical plunge, punching a neat hole in the water and throwing up a plume of white spray. You watch its vapour trail of bubbles twist and turn as it chases after a fish. All around you others are doing the same, almost close enough but much too fast to touch. Later, you wait on a grassy island slope through the long summer evening as rafts of Manx Shearwaters gather offshore, the warm evening light flushing their white chests rosy. As darkness falls they head for land; suddenly they are everywhere, blundering past you to their burrows, shouting to their chicks underground, the cacophony of their bizarre voices growing as the night takes over, until you are alone in an alien soundscape.

The people of our island nation have long drawn inspiration from the sea. Its richness, power and mystery infuse our identity, and many of us also have a special respect and affection for the birds that make their living as seafarers. Like the sea itself, seabirds seem to have a special wildness and freedom compared with even the most elusive land birds, and yet are among the easiest of all our birds to observe at close quarters, offering wildlife-watching experiences of incredible intensity.

Compared with many countries in mainland Europe, the UK and Ireland have a rather sparse, impoverished wildlife population. The great mammalian predators of our forests are long gone, and many of the mainlands plants and small animals simply never reached us. Due to our dense human population true wilderness is hard to find. However, turn away from the land, look to the sea, and suddenly we are punching well above our weight in terms of wildness.

Great Britain has about 18,000km of coastline. Add Irelands coastline and that is another nearly 2,800km. The hundreds of smaller islands all around our coastline almost double this total. Along that great length of coastline there are beaches of boulder, shell and stone; sheer chalk and granite cliffs; softly crumbling slopes of sandstone and mud; dunes anchored by marram grass into towering crested ridges; estuarine mudflats and saltmarshes, and seaside towns of every character. All of these provide habitats for wildlife, as of course does the open sea itself.

Our seabirds, perhaps more than any other animals, have a foot in both worlds, needing dry land to nest and rear their young, but relying on the sea for their foraging. Every detail of their anatomy, from the colours of their plumage to the structure of their bones, speaks of adaptation to a life in intimate association with the open sea, and their behaviour is no less specialised. Most seabirds are intelligent and long lived, many form pair bonds that can endure for decades, while two of our seabirds the Arctic Tern, which breeds here, and the Sooty Shearwater, which is a regular visitor to British coasts are extreme long-distance travellers, each regularly flying 65,000km or more in a year.

The British Isles are of global importance for their breeding seabirds. It includes more than half the worlds entire breeding populations of three species the Manx Shearwater, Gannet and Great Skua. Of the remaining 22 seabird species that regularly breed around our coasts, 18 in Britain and eight in Ireland have internationally important populations. Outside the breeding season, the seas around the British Isles support huge numbers of other seabird species that breed inland or on coasts elsewhere.

A WILDERNESS OF WATER

The Atlantic Ocean surrounds us on all sides and extends across more than 20 per cent of the worlds surface. Marine life around the British coastline is both plentiful and diverse. The North Sea supports one of the worlds richest and most important fisheries, and the mackerel, cod, whiting and plaice that the boats bring in each day are a tiny part of a huge ecological web, representing thousands of genera across the full sweep of biological life. Seabirds prey not only on fish of an array of species, but on squid, crustaceans, like copepods and shrimp, seabed-dwelling molluscs, such as mussels, the floating or washed-up bodies of dead sea mammals and, in some cases, each other. Some, such as the storm-petrels, are specialists at picking floating prey from the surface, while others are deep divers the Razorbill can propel itself to depths of 120m. The most adaptable eaters are the large gulls, which can catch fish quite proficiently but (in seaside towns at least) are just as likely to lunch on the contents of a ripped-open bin bag, or a Cornish pasty expertly swiped from an unsuspecting tourists hand.