Contents

Guide

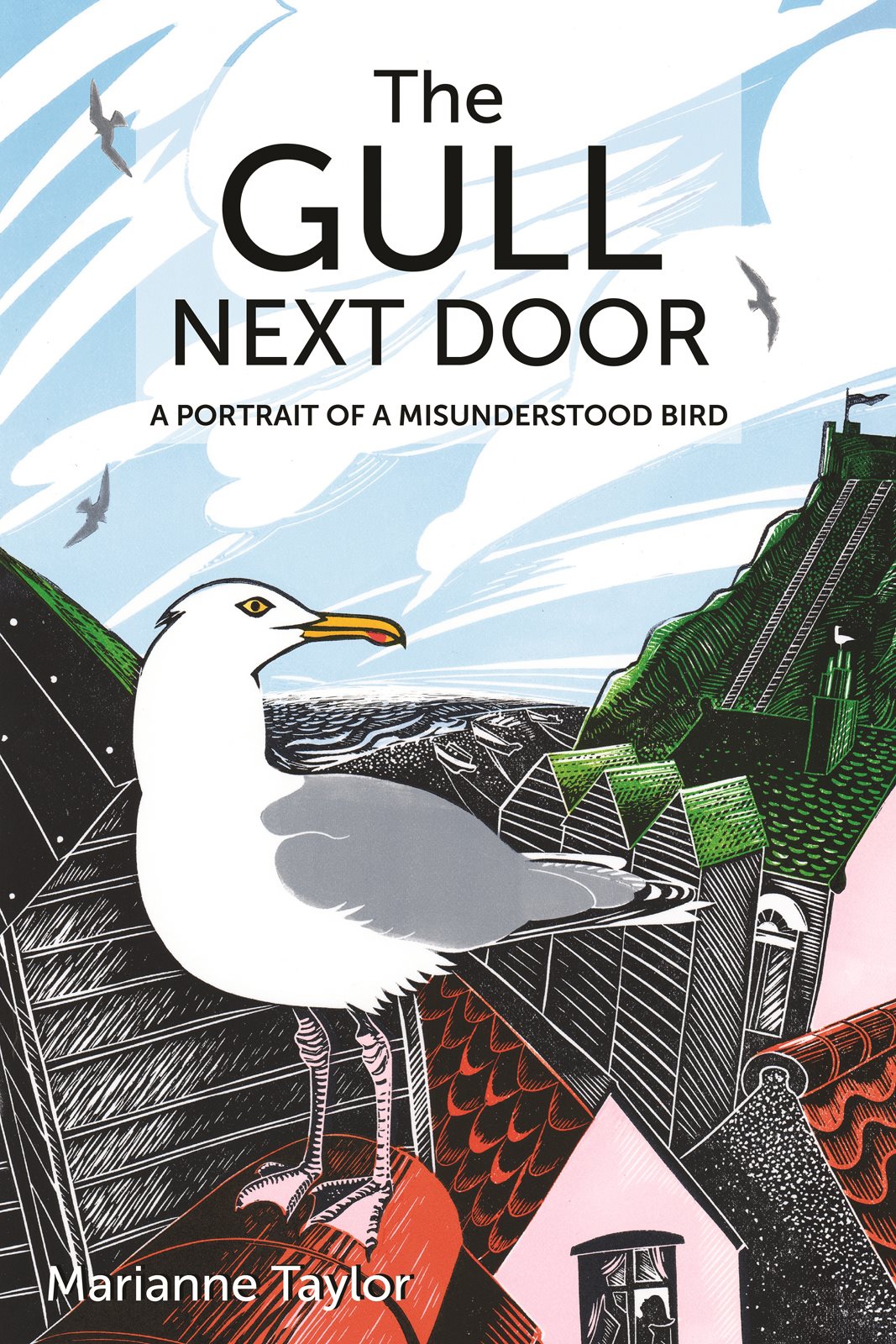

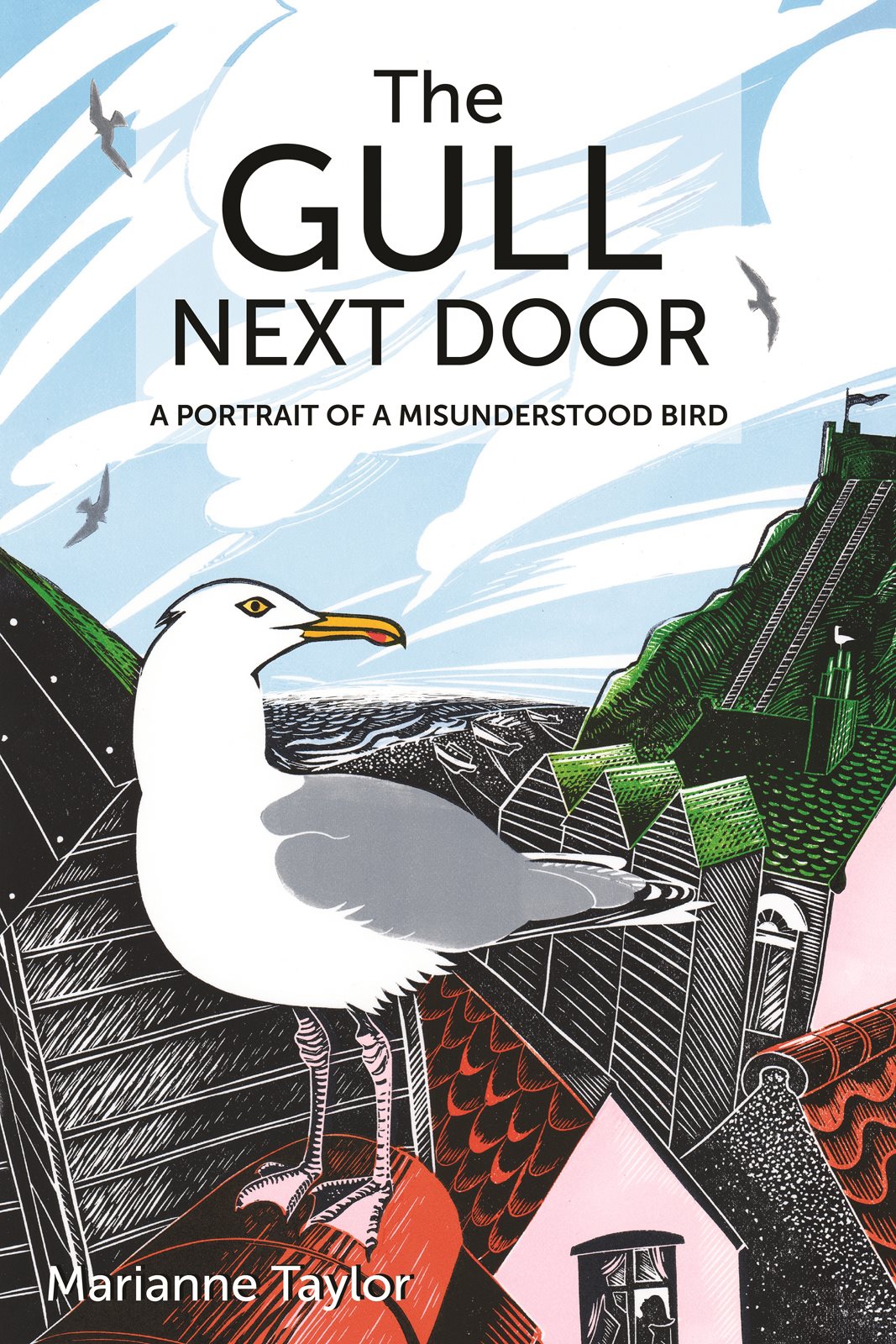

THE GULL NEXT DOOR

A Portrait of a Misunderstood Bird

THE GULL NEXT DOOR

A Portrait of a Misunderstood Bird

Marianne Taylor

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

First published 2020

Copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press

Illustrations copyright 2020 by Marianne Taylor

Copyright in the photographs remains with the individual photographers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Library of Congress Control Number 2020940432

ISBN 978-0-691-20896-1

Ebook ISBN 978-0-691-21086-5

Version 1.0

Production and design by WILDNATUREPRESS Ltd., Plymouth, UK

Contents

Chapter 1

Britains Gulls 13

Chapter 2

Natural and Unnatural History 43

Chapter 3

The Herring Gull 73

Chapter 4

Gulls and People 97

Chapter 5

Gulls in Word and Image 119

Chapter 6

Larophilia 133

Chapter 7

Moving On 159

Chapter 8

2019 A Gull Postscript 171

Foreword

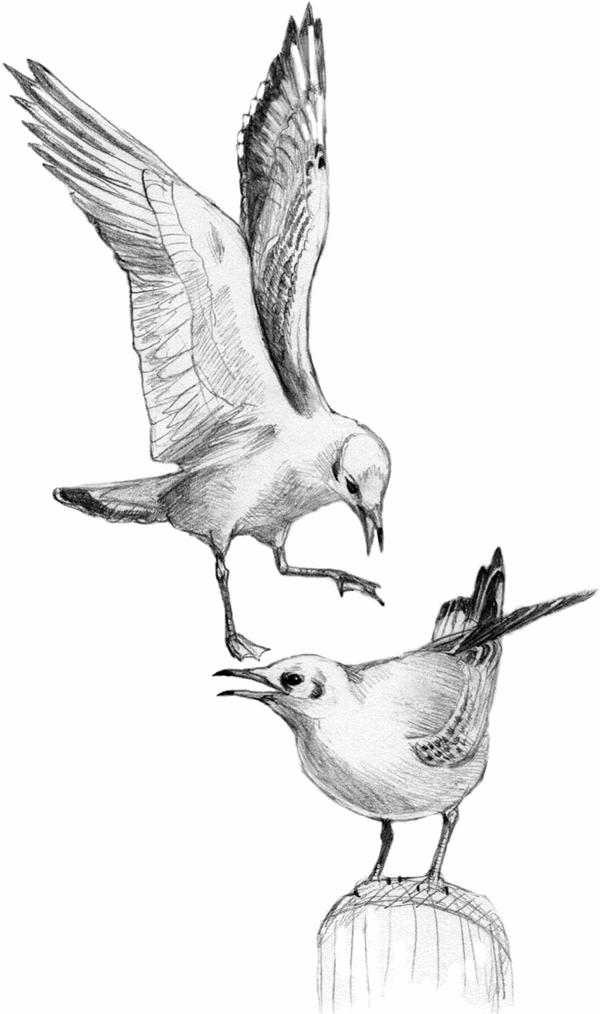

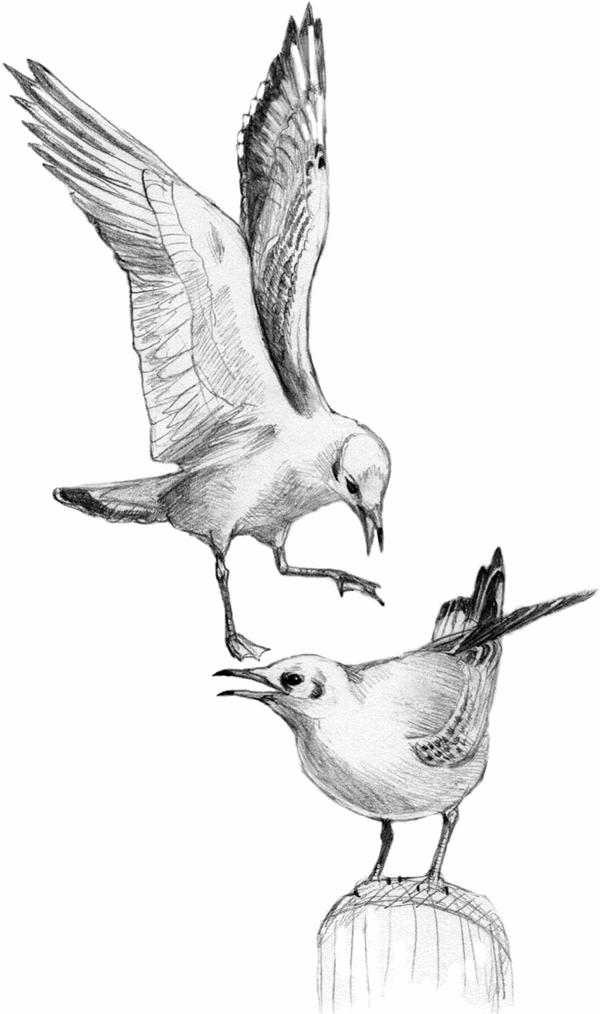

Black-headed gulls

Huge seagulls that nick your Mr Whippy are the thoughts that many members of the public have when asked to talk about this family of birds. Gulls are a bit of a dichotomy. On the one hand, they are glorious masters of the sea and air, beautiful and even occasionally colourful, with some species bearing a beautiful rosy-pink hue to their otherwise largely grey and white plumage. On the flip side, they are much-maligned members of the avian world, often vilified for assault and battery by the popular press.

Even birders have mixed feelings about them. Stop a random, binocular-wielding nature lover in the field and most will say that they give up on the gull family because the immature birds are devilishly difficult to decipher. Indeed, I know people that will actively overlook gulls for fear of getting brain-strain. Of course, at the other end of the birders spectrum are the confirmed larophiles, or gullers, who live to count mirrors on P5-P10s. You either love or hate watching them, it would seem. There appears to be no middle ground. Even the literature dedicated to them is aimed at the techie and sometimes, nerdy ornithologist.

Enter Marianne Taylor. Now, although I will have to admit that I am a massive fan of her writing, I will also have to say that at last in The Gull Next Door, there is now a book that bridges the gap between the nervous wannabe gull-lover and the confirmed larophile. It is an endearing, gentle and very personal account from a woman who has grown to love gulls. Within the pages of this book you will be introduced in a very relaxed and chilled way into the world of the gulls that frequent the UK. There is a tremendous spread of gull information imparted here and I guarantee that by the end you will have fallen in love.

Thank you Marianne.

David Lindo

30 April 2020

To Penny

Thank you for your words, wisdom and boundless kindness.

Squawk!

Prologue

The Old Town of Hastings sits between two steep hills. The one to the west is called the West Hill while the other, unsurprisingly, is the East Hill. The West Hill is smaller, just a big hump of mostly mown grass surrounded by streets, with a low bit of weathered sandstone cliff now well separated from the sea. This mini-cliff supports on its crown the ruins of Hastings Castle. The East Hill, its sheer cliffs slowly crumbling into the sea beyond the edge of the town, climbs steeply to its expansive, undulating summit of grassland and the gorse-cloaked Firehills, cut through with wooded ravines. The hilly ridge extends some 15 miles east along the coast to Fairlight, where every tree grows up leaning away from the incessant wind. Then the landscape dives down to the open floodplain of Romney Marsh, and on to Rye and the southern coast of Kent.

We lived in a very tall, thin town house on the west side of the Old Town, and from my sisters bedroom on the top floor I could see almost every house in this part of town. They were a colourful jumble of mismatched buildings pretty Tudor cottages with doorways that even 53 me would have to duck to enter, blocky grey 1970s eyesores, and everything in between. They always looked to me as though they had all slid down the hillsides to land in a disorderly pile in the bottom of the valley.

I wasnt overly fascinated by this mixed-up, chaotic town, though, despite its wealth of historical interest. What caught my attention was the other town, the town-on-top-of-the-town, the town of the gulls. The Old Town had a thriving herring gull population. They built their homes on the roofs of ours, scruffy nests of dead grass stuffed in between the chimney pots, and they commuted to the beach for their daily diet of stolen fish and scavenged chips. Through the day and much of the night their voices rose above all the sounds of the street, in endless muttered and screamed conversations with partners, neighbours and rivals. By early summer there were fluffy grey chicks hatching from eggs laid in the chimney-pot nests, and soon these youngsters were out and about, pattering across the rooftops and adding their own piping voices to the general cacophony.

It only took a few weeks for that cute baby fluff to be replaced with muddy grey juvenile plumage and the sweet whistling voice to break into a sore-throated, gargling version of the adults squawk. Each year, some of the adolescent gulls on our roof jumped before they could fly, and landed on our patio where they were at risk of fisticuffs with the family cats. As the household bird person, it fell to me each time to catch the errant youngster in a towel, carry it up through the house and post it out of the skylight back onto the rooftop. One day, I was engaged in this task when the young gull in my arms twisted round in its towel and lunged at my face, the blade of its bill leaving a thin but lengthy wound across my left cheek. This painful experience didnt diminish my fondness for the gulls at all but it did increase my respect for them, and thereafter I made sure the towel always covered their heads.

I would sometimes peer through the skylight at our rooftop gulls just to see what they were up to, and on one occasion I saw an adult bird that didnt look very well. Sitting on its belly with eyes half shut, it failed to respond to me tapping on the window. My gull-rescuer instincts kicked in again, and I opened the skylight and climbed out onto the narrow flat bit of the roof. The gull got to its feet with some difficulty and hobbled to the roofs edge but made no attempt to launch into flight. I caught it and brought it down into the house, where I gave it food and water. After a couple of days TLC in the garden shed, it was walking normally, and in another day or two was beating its wings and looking fully recovered, so I let it out into the garden and it took flight. (Although I thought little of it at the time, I now find that I cannot look back on those few moments chasing down a gull on top of the roof of our six-storey house without feeling extremely sick and trembly.)