William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2019

Copyright John C. Coulson, 2019

Photographs Individual copyright holders

John C. Coulson asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

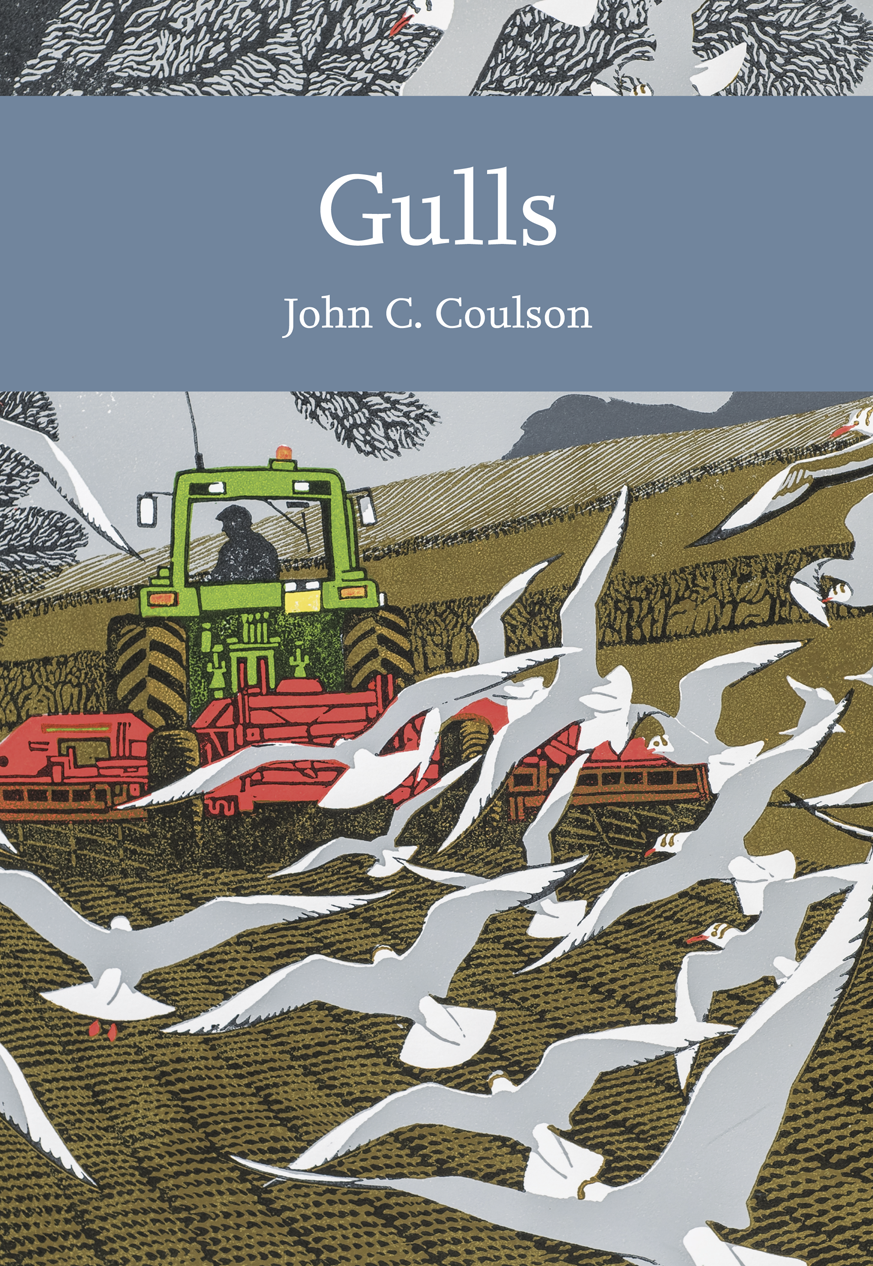

Cover design linocut by Robert Gillmor

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008201425

Ebook Edition April 2019 ISBN: 9780008201449

Version: 2019-02-11

EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, S C D

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FRSB

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIH ORT

P ROF . JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

P ROF . BRIAN SHORT

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

Contents

G ULLS ARE A FAMILY OF DISTINCTIVE and easily recognised birds that are familiar to us all, whether we live close to the sea or many miles inland, and whether we live in urban or rural surroundings. Long gone are the days when the sight of flocks of gulls overhead or in nearby fields was taken as a sure and ominous sign of storms at sea. For most of us today, birdwatchers or not, gulls are genuinely everyday birds, as common a sight as Woodpigeons ( Columba palumbus ) or the various members of the crow family. Other than in immature plumages (which may cause problems), the handful of commoner species are readily identifiable to those with any interest.

Seeking an expert author for a new book on gulls was a relatively easy task for the editors. Dr John Coulson was, until his retirement, Reader in Animal Ecology at the University of Durham, and has a lifetimes experience of research into many aspects of gull (and other seabird) biology and ecology, with a particular focus on the Black-legged Kittiwake ( Rissa tridactyla ). He is an expert of world renown, and recipient in 1992 of the British Ornithologists Unions highest accolade, the Godman-Salvin Medal, and in 1993 of the Waterbird Societys Robert Cushman Murphy Prize.

A fulsome initial chapter introduces the gull family as a whole, including a succinct assessment of the rather complex current (worldwide) status of gull taxonomy. Things have changed dramatically since the eighteenth century, when Carl Linnaeus first established the single genus Larus , containing all the then known species! After this, the reader is treated to nine chapters each in effect a treatise on the regular British and Irish gulls, including the latest newcomer, the rapidly increasing and very elegant Mediterranean Gull ( Ichthyaetus melanocephalus ). These are followed by chapters on the rarer species; methods used in studying gulls; urban problems; and conservation, management and exploitation.

In common with many components of our fauna and flora, times have changed for gulls, and not always for the better as the author describes. They may not universally be seen as slender-winged, elegant seabirds, and to some especially those living in or visiting towns or cities with rooftop gull colonies they are raucously noisy neighbours. Similarly, many seaside promenades are blighted by the menacing presence of gulls with unblinking eyes seeking scraps, often boldly. Since the late twentieth century, even conservation bodies seeking to encourage nesting terns or other seabirds have resorted to culling in an attempt to limit predatory gull activity. In the last few decades, however, Herring Gull numbers, boosted in the second half of the twentieth century by the ready feeding opportunities offered by poorly covered landfill sites, have fallen to the extent that they themselves have become of conservation concern.

Such problems, as well as the many fascinating but less nefarious aspects of our British and Irish gull populations, are dealt with in substantial detail in John Coulsons admirably comprehensive text. This is a most noteworthy addition to the New Naturalist Library.

M Y FIRST RECOLLECTION OF GULLS was when I was about eight years old, when a maritime pilot on the Tyne told me that the gulls that frequently followed commercial ships entering the busy river were the reincarnations of past pilots, and were keeping a supportive eye on the steering of current pilots. An individual gull the pilots recognised because it called frequently was said to be the reincarnation of pilot Clagger Purvis, who apparently had had as much to say for himself in life. Even at that age I found this story hard to believe, but the pilot was right about the frequency of gulls following both large and small vessels into the river.

My interest in birds, and particularly in gulls, developed during my school days. As a member of a small group mentored by Fred Grey, a master at South Shields High School for Boys and a person with a lifelong passion for birds, I learned much about the identification of birds during mid-morning breaks and on field trips. Through his guidance, my questioning eventually expanded from What is it? to What is it doing? I was also very much influenced by the Reverend Edward Armstrongs book Bird Display and Behaviour (1942), David Lacks The Life of the Robin (1943) and, in particular, Sir Arthur Landsborough Thomsons Bird Migration (1936), which highlighted some of the information that could be gained by ringing birds.

While still in the sixth form at school, I wrote to Elsie Leach, who ran the national bird-ringing scheme in an honorary capacity for the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) from a small office and a cupboard in the Natural History Museum in London, asking her how to become a ringer. I received a prompt response requesting a letter of support from an acknowledged ornithologist that I could identify birds. I obtained this from a local doctor; he had an excellent knowledge of the birds of northern Norway and I had previously been able to draw his attention to uncommon birds visiting the vicinity, which he would stop off to see while making slight detours en route to his house calls.

Having sent the recommendation to Miss Leach, I received a reply within a few days simply asking what numbers and sizes of rings I wanted. At that time, 1948, there was no training whatsoever for potential ringers, nor an age limit. Every ring used had to be recorded on a thin cardboard sheet, which took only six ring entries and was guillotined into separate strips if the ringed bird was recovered. Ringing was on a very much smaller scale in those days! I remained an active ringer for 62 years, and have seen many changes to the British ringing scheme, including the intensive training now required for those who wish to ring. I also received one of the first mist nests in the country, and had to work out for myself how to use it all I was told was to hang it between two poles!