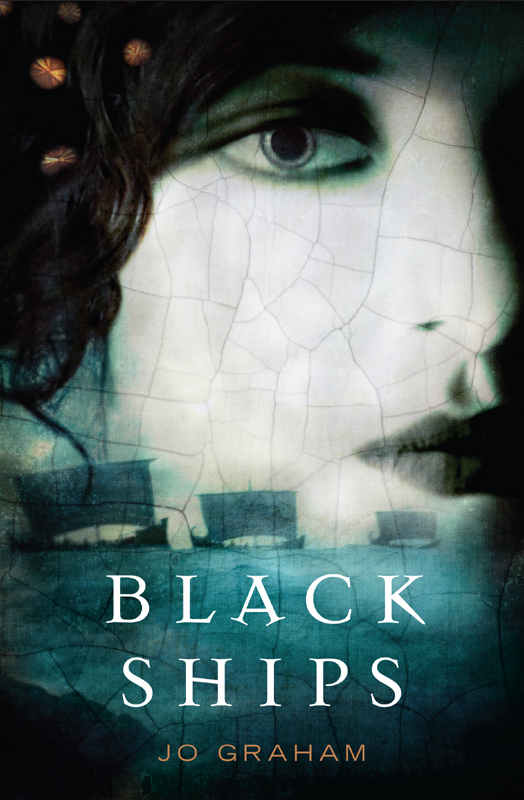

Copyright 2008 by Jo Wyrick

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Orbit

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

First eBook Edition: March 2008

Orbit is an imprint of Hachette Book Group USA.

The Orbit name and logo are trademarks of Little, Brown Book Group Limited.

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-02914-8

For my father, Glenn Wyrick,

who gave me The Last of the Wine

when I was eleven and a half

At Pylos in particular groups of women are recorded doing menial tasks such as grinding corn, preparing flax, and spinning. Their ration quotas suggest they are to be numbered in the hundreds.... At Pylos there is even an enigmatic To-ro-ja (woman of Troy), servant of the god.

Michael Wood, In Search of the Trojan War

PYTHIA

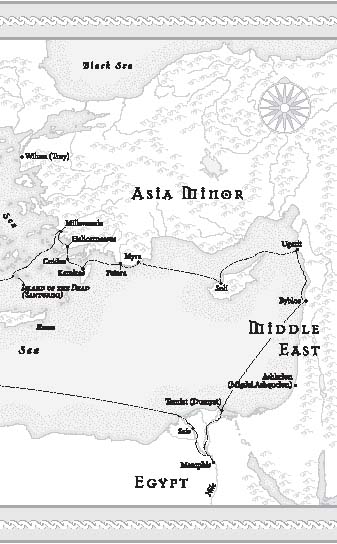

Y ou must know that, despite all else I am, I am of the People. My grandfather was a boatbuilder in the Lower City. He built fishing boats, my mother said, and once worked on one of the great ships that plied the coast and out to the islands. My mother was his only daughter. She was fourteen and newly betrothed when the City fell.

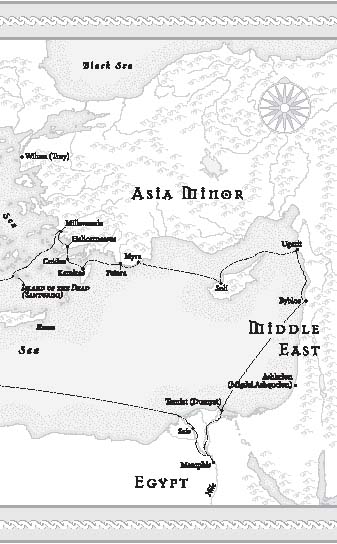

The soldiers took her in the front room of the house while her fathers body cooled in the street outside. When they were done with her she was brought out to where the ships were beached outside the ring of our harbor, and the Achaians drew lots for her with the other women of the City.

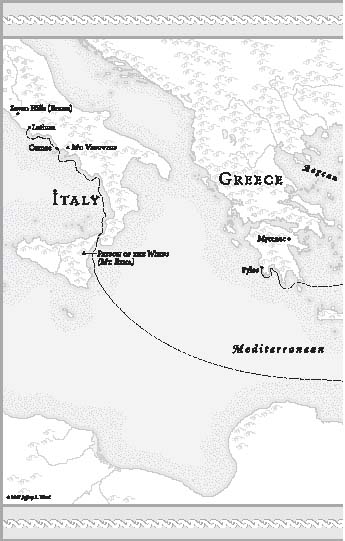

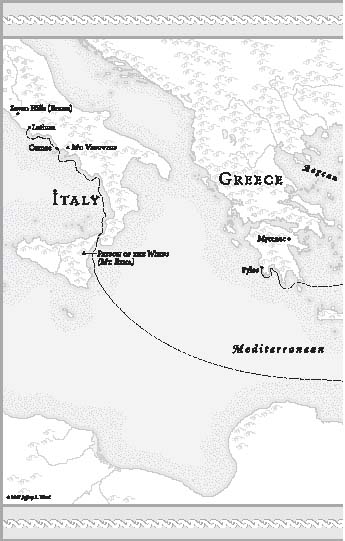

She fell to the lot of the Old King of Pylos and was brought across the seas before the winter storms made the trip impossible. She was ill on the vessel, but thought it was just the motion of the ship. By the time she got to Pylos it was clear that it was more than that.

King Nestor was old even then, and he had daughters of the great houses of Wilusa to spin and grind meal for him, slaves to his table and loom. He had no use for the daughter of a boatbuilder whose belly already swelled with the seed of an unknown man, so my mother was put to the work of the linen slaves, the women who tend the flax that grows along the river.

I was born there at the height of summer, when the land itself is sleeping and the Great Lady rules over the lands beneath the earth while our world bakes in the sun. I was born on the night of the first rising of Sothis, though I did not know for many years what that meant.

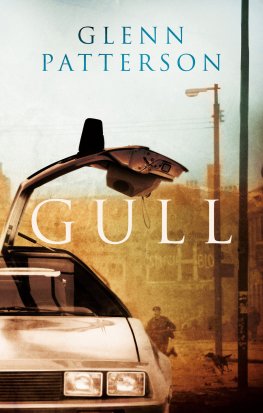

My mother was a boatbuilders daughter who had lived all her life within the sound of the sea. Now it was a mornings walk away, and she might not go there because of her bondage. Perhaps it was homesickness, or perhaps something in the sound of my newborn mewing cries, that caused her to name me Gull, after the black-winged seabirds that had swooped and cried around the Lower City.

By the time the autumn rains came, I was large enough to be carried in a sling on my mothers back while she worked.

I know it was not that year, but it is my first memory, the green light slanting through the trees that arched over the river, the sound of the water falling over shallow stones, the songs of the women from Wilusa and Lydia as they worked at the flax. I learned their songs as my first tongue, the tongue of the People as women speak it in exile.

There were other children among the linen slaves, though I was the oldest of the ones from Wilusa. There were Lydians older than I, whose mothers had come from far southward down the coast, and a blond Illyrian from north and west of Pylos. Her name was Kyla; she was my childhood friend, the one who paddled with me in the river while our mothers worked. At least until she was also put to work. I knew then what my life would bethe steady rhythm of beating the flax, of harvest and the life of the river. I could imagine no more. The tiny world of the river was still large enough for me.

The summer that I was four was the summer that Triotes came. He was the sister-son of the Old King, tall and blond and handsome as the summer sun. He stopped to water his horses, and talked with my mother. I thought it was odd.

A few days later he came again. I remember watching them talking, Triotes standing at his horses heads, ankle deep in the river. I remember thinking something was wrong. My mother was not supposed to smile.

He came often after that. And sometimes I was sent to sleep with Kyla and her mother.

My fifth summer was when my brother was born. He had soft, fair baby hair, and his eyes were the clear gray-blue of the sea. I looked at my reflection in the river, at my hair as dark as my mothers, eyes like pools of night. And I understood something new. My brother was different.

Triotes threw him high in the air to make him laugh, showed him to his friends when they led their chariots along the road. He was barely a man himself, and he had no sons before, even by a slave. He brought my mother presents.

One night I heard them talking. He was promising that when my brother was older he would bring him to the palace at Pylos, where he would learn to carry the wine cups for princes, where he would learn to use a sword. He was the son of Triotes, and would be known as such.

Later, when he had gone, I crept in beside my mother. My brother, Aren, was at her breast. I watched him nurse for a few minutes. Then I laid down and put my head on my mothers flat, fair stomach.

Whats the matter, my Gull? she said.

I am the daughter of no man, I said.

I do not think she had expected that. I heard her breath catch. You are the daughter of the People, she said firmly. You are a daughter of Wilusa. I was born in the shadow of the Great Tower, where the Lower Harbor meets the road. I lived my whole life in the sound of the sea. Your grandfather was a boatbuilder in the Lower City. You are a daughter of Wilusa. My mother stroked my hair with her free hand, the one that did not support Aren. You were meant to be born there. But the gods intervened.

Then wont the gods intervene again and take us back? I asked.

My mother smiled sadly. I dont think the gods do things like that.

And so I returned to the river. I was old enough to help the women with the flax in the green cool twilight along the water. And this, I knew, was where I would spend my life.

I dont remember the accident that changed all that.

We often played along the road that paralleled the river. It was nothing more than a packed track, rutted from chariots and carts. I remember the chariot, much finer than Triotes, the blood bay horses, the gleaming bronze. I remember staring transfixed. I remember my mothers scream, high and shrill like a gull herself.

It was fortunate that the rains had begun and the road was muddy. The wheel passed over my right leg just above the ankle, snapping the bones cleanly, but not cutting my foot off, as I have seen happen since. The road was muddy, and the surface gave.

I remember little of that winter. I dont remember how long I spent on the pallet in the corner where my mother had given birth to Aren. Perhaps its childhood distance. Perhaps its the essence of poppy that the oldest of the slave women gave me for the pain. I vaguely remember picking at the wrappings around my leg and being told to stop. And that is all.