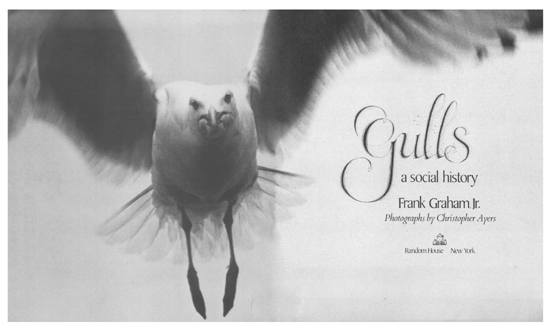

Copyright 1975 by Frank Graham, Jr., and Christopher Ayres

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Graham, Frank, 1925

Gulls: a social history.

1. Gulls. 2. ZoologyEcology. I. Ayres,

Christopher. II. Title.

QL696.C46G7 598.33 75-10265

eISBN: 978-0-307-82879-8

v3.1

Authors Note

T his is a book about gulls and men, not primarily a natural history of gulls, but, rather, a social historya record of the relations between man and several of the worlds forty-four gull species.

I have chosen to write about gulls instead of humming-birds or herons or eagles because of all birds, none seems to me to reveal such a variety of effectsand countereffectsfrom their contact with man as gulls do. They are remarkable creatures in their own right, as I hope to show. But some kinds of gulls have been temporarily thrown out of context with their world because of mans inability to see that world in all its complexity. What has happened to these birds is related to our larger environmental problems. In all its dimensions, this is a case history in ecology.

Like anyone else who writes about gulls today, I owe a large debt to the Dutch naturalist Niko Tinbergen and his works. It is also becoming apparent that anyone who writes about gulls owes a debt to the research and observation of William H. Drury of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. I would like to thank Dr. Drury for making his material available to me, and for being additionally generous with his time and knowledge while I was writing this book.

I would further like to thank the following men and women for making my work on this book a great deal easier: Richard B. Anderson, Carl H. Buchheister, Frank Gramlich, Jeremy J. Hatch, Charles E. Huntington, Les Line, Ian C. T. Nisbet, Marjorie Spock, and Marion and David Stocking.

Several parts of this book originally appeared in Audubon, and I am grateful for permission to reprint them here.

A list of the worlds forty-four gull species and bibliographical notes appear at the end of the book.

Frank Graham, Jr.

Milbridge, Maine

Contents

Prologue

W e were a curiously mixed group who set forth one morning in mid-June aboard a lobster boat into Maines Muscongus Bay, with the means of slaughter and renewal heaped around us on the open deck. A mild breeze scarcely troubled the bays surface. The early-morning fog dissipated itself in convoluted wisps, tinctured gold now by the pour of light from the climbing sun. Our boat moved down the bay, dropping astern the inshore islands, which were covered with dense spruce stands of an unvarying dark green. The large skiff we towed alternately lunged and heeled over in our wake.

Our destination was Eastern Egg Rock at the mouth of the bay, but our purpose was double-edged. Steve Kress, who stood across the deck from me, his legs slightly apart and bent to absorb the lift of our buoyant craft, is an ornithologist. A tam-o-shanter sat rakishly on his thick curly hair, and his face was bright with the thrill of something ventured. The three college students who were his assistants, two women and a tall young man, leaned on the gunwales or sat on the stacks of lumber and ceramic chimney tiles near him.

It will be fantastic if it works, Kress was saying. We think it will work. A lot of thought and preparation has gone into it.

Kress, who is on the staff of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology and spends the summer months at the Audubon Camp of Maine, had devised a plan to restore the common puffin, that marvelous little sea parrot with the bizarre, multicolored bill, to Muscongus Bay, from which it disappeared at the turn of the century. Some large puffin colonies remain off the northern coasts of Canada and Europe. But the bird now nests in rocky burrows on only two small, remote island colonies along the East Coast of the United StatesMatinicus Rock, off Rockland, Maine, and Machias Seal Island, to which Canada holds a disputed claim. On this day Kress and the students were taking to Eastern Egg Rock the stuff with which to fashion puffin burrows. In a few weeks Kress would fly to Canada and receive from Canadian wildlife authorities sixty-five puffin chicks, removed for the purpose from flourishing colonies off Newfoundland.

These tiles are seven inches square, and about four feet long, just long enough to make a good puffin burrow, Kress continued. We want to start these chicks in artificial burrows so we can feed them and know just where they are. Therell be wire covers over the ends of the tiles to keep out gulls. And well hand-feed the chicks with smelts that we can buy frozen. Puffins come back to breed on the island where they were raised. Were hoping that when these chicks maturein three or four yearstheyll come back to breed on Eastern Egg Rock and maybe found a new colony here.

Historically, this has been a productive area for sea birds. I knew Wreck Island, which we were just passing, for I had explored it a decade earlier while I was at the Audubon Camp, which lies at the head of the bay. Wreck Island is a boreal jungle, a green riot of ferns and shrubs in a congestion of trees, heavily fertilized by the nesting great blue herons and black-crowned night herons. Its crepuscular interior is harsh with the incessant fronk and quowk of the agitated birds. But else where in the bay the nesting islands are dominated by gullsthe Herring Gull, which is the common seagull of the East Coast, and in increasing numbers its larger relative, the Great Black-backed Gull.

And that was why we had another party aboard. Its leader was Frank Gramlich of the Division of Wildlife Services of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The divisions name is something of a euphemism because the services it performs have mostly to do with the elimination of birds and mammals inimical to what man thinks are his best interests. It is the successor, its image refurbished, to the old Predator and Rodent Control branch of the Fish and Wildlife Service, and it has stamped out unwanted creatures of all kinds, from mountain lions, coyotes and gophers in the western wilderness to rats and pigeons in the less exalted wilds of eastern cities. On this day Gramlich was on a gull control mission to Eastern Egg Rock.

One would look a long time to find a man less likely to fit the mold of a wildlife exterminator. No one who knows him says a mean word about Frank Gramlich. He has the face of Huck Finn sagging a little at the prospect of middle age, his boyish smile is shy but infectious, his nature is unfailingly considerate. He is alert to the glories of wild things and the needless abuses to which man has subjected them. On the way to the island now he was saying that it was an old dream of his to see the rattlesnake someday reintroduced to Maine, from which man had extirpated it long ago. The state, he said, was the poorer for losing it; there was room here for rattlesnakes, as well as for puffins, bears, gulls and coyotes.