For all items sold, Bloomsbury Publishing will donate a minimum of 2% of the publishers receipts from sales of licensed titles to RSPB Sales Ltd, the trading subsidiary of the RSPB. Subsequent sellers of this book are not commercial participators for the purpose of Part II of the Charities Act 1992.

Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2017 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2017

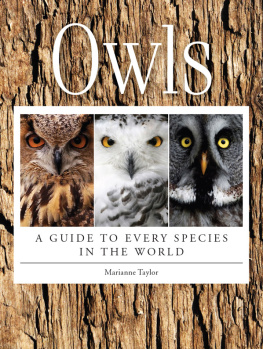

Marianne Taylor, 2017

Photographs and illustrations as credited , 2017

Marianne Taylor has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3369-0 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3371-3 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3370-6 (ePDF)

Design by Rod Teasdale

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

Copyright in the book covers shown : The front cover of The Owl Service is reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 1967 Alan Garner

From The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson. Illustrations copyright 2004 Paul Howard. Published by Egmont UK Ltd and used with permission.

Front cover of Little Owls Egg reproduced by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 2016 Debi Gliori, illustrations by Alison Brown

Front cover of Thats Not My Owl reproduced by permission of Usborne Publishing, 8385 Saffron Hill, London EC1N 8RT, UK. www.usborne.com. Copyright 2015 Usborne Publishing Ltd.

Contents

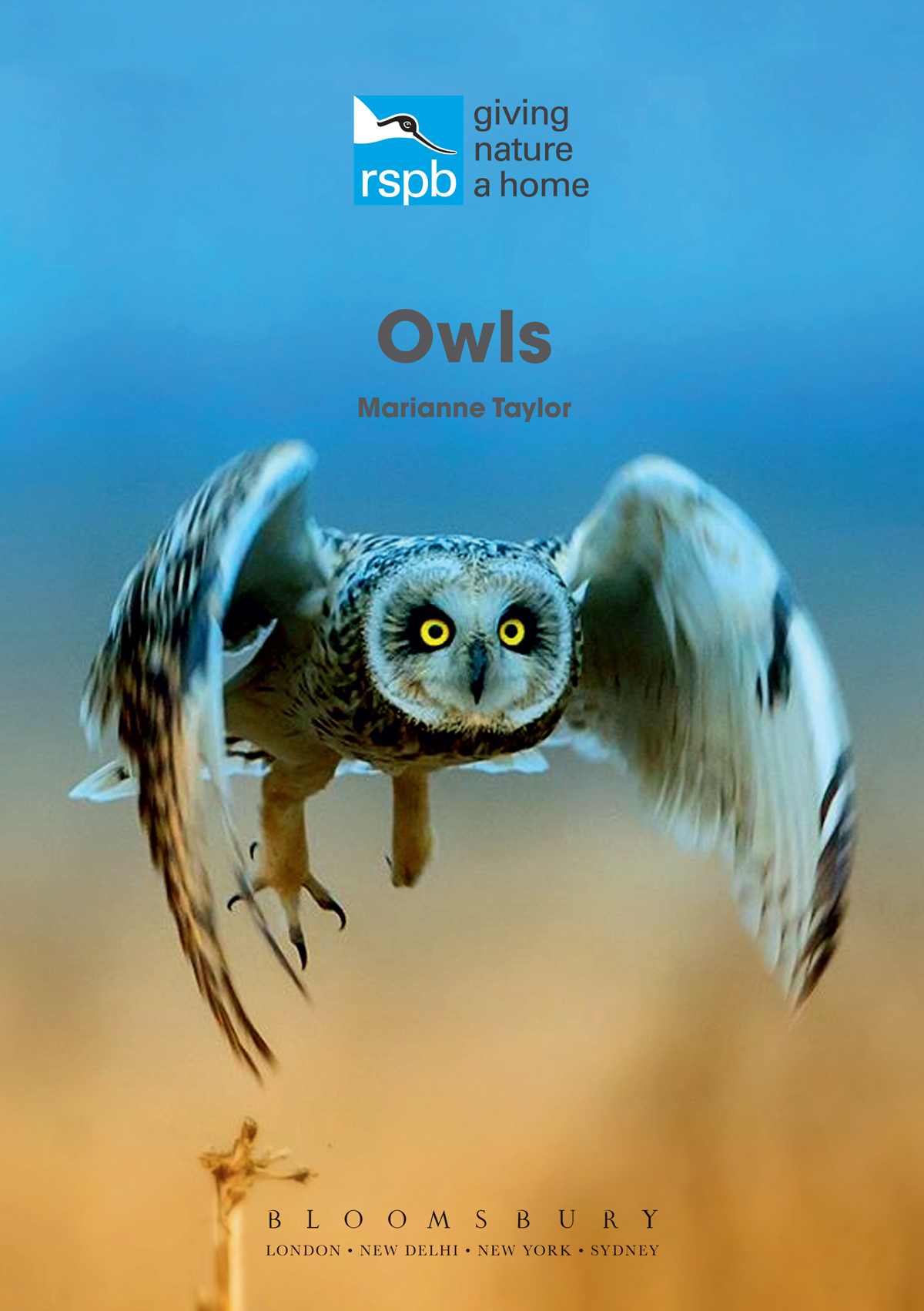

The ethereal beauty of the Snowy Owl.

Meet the Owls

A haunting, fluted hoot that jolts you out of sleep at 4am. A white ghost freeze-framed in your headlights on a dusk drive home in winter. A furious little face staring at you from the crack in an old barn roof. Encounters with owls in Britain are often startling and always memorable. Few other birds evoke such a strong sense of magic and mystery and if you meet their gaze understanding and connection, or at least the illusion of such. Its almost impossible to look at the face of an owl and not attribute some human quality to its expression.

Secret lives

Wherever we live on the planet, almost all of us know an owl when we see one; its forward-facing eyes seem to burn into our own. Centuries of fanciful folklore have bumped owls higher up in our cultural consciousness than perhaps any other birds, even though most of us only see owls infrequently in our everyday lives, if at all. The nocturnal habits and deep forest habitats of some owls, coupled with predatory powers that seem to almost defy nature and a repertoire of haunting and frightening calls, endow them with a mystique as irresistible as it is potent.

A Tawny Owl sitting at its tree-hole nest is the very image of a 'wise old owl' of the woods.

In this age of television, YouTube and Facebook, we now have opportunities to see owls in action in different settings, without having to take a midnight walk in the woods. Through skilled camerawork we can see for ourselves how owls use their remarkable senses to find and catch their prey, overcoming challenging conditions that most other animals would find impossible to handle. We can also watch rescued or trained captive-bred birds interacting with their keepers, revealing depths of charm, adventurousness and intelligence that vastly add to their appeal. Yet the day-to-day lives of wild owls remain rather mysterious, though our knowledge and understanding of them is growing by the day.

Short-eared Owls seem to be more sociable than most other species, but this behaviour is still not well understood.

In Britain, there are five species of owls regularly breeding in any numbers. Thats a tiny proportion of the world total of more than 200 species. However, these five owls are quite a diverse bunch, in size, shape, colour, habits and personality. In short, they demonstrate five very different ways to be an owl. In addition to these five, a few other species (again, all very different) make occasional guest appearances in the wild in Britain.

File under O

The term bird of prey denotes a bird that hunts and eats other vertebrate animals. Many birds, from rails to herons and gamebirds to songbirds, may do this from time to time. However, the title of bird of prey usually applies only to the members of three distinct groups, all noted for their predatory ways: the hawks and their allies (eagles, kites, buzzards, harriers and the like); the falcons; and the owls. The differences between owls and the rest have long been acknowledged, and their distinction recognised. Traditionally hawks and falcons are known as diurnal birds of prey, or raptors/diurnal raptors, and in field guides they are treated separately to the owls.

Today, biologists can work at the genetic level to investigate how closely related various bird groups really are, and their research has found evidence that the owls may actually be more closely related to the hawks than the falcons are. In any case, the similarities between a buzzard, a kestrel and an owl owe more to convergent evolution (whereby animals that pursue similar lifestyles evolve similar characteristics over time as with dolphins and fish, for example) than to relatedness. The bird-of-prey lifestyle has arisen separately in two or more distinct bird lineages. Being a hunter of other vertebrates is a good way for a bird to make a living if it is done right. It is much more difficult to catch a relatively large, clever animal than it is to pick up an insect, but just one good-sized kill a day is often enough to meet the hunters nutritional needs. The specialist hunters in the bird world all have superlative senses to find active, intelligent prey, the brainpower to outwit it, the speed and strength to overcome and catch it, and the physical equipment of talons and a hooked bill to kill and consume it.