My father, Phillip Glasier, flying Islay, his female Harris Hawk. He has permission from many kind landowners to fly over thousands of acres

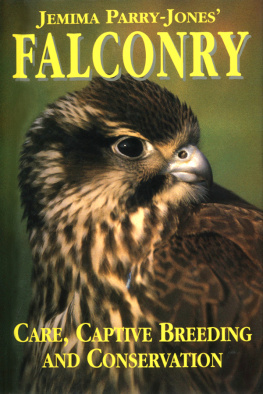

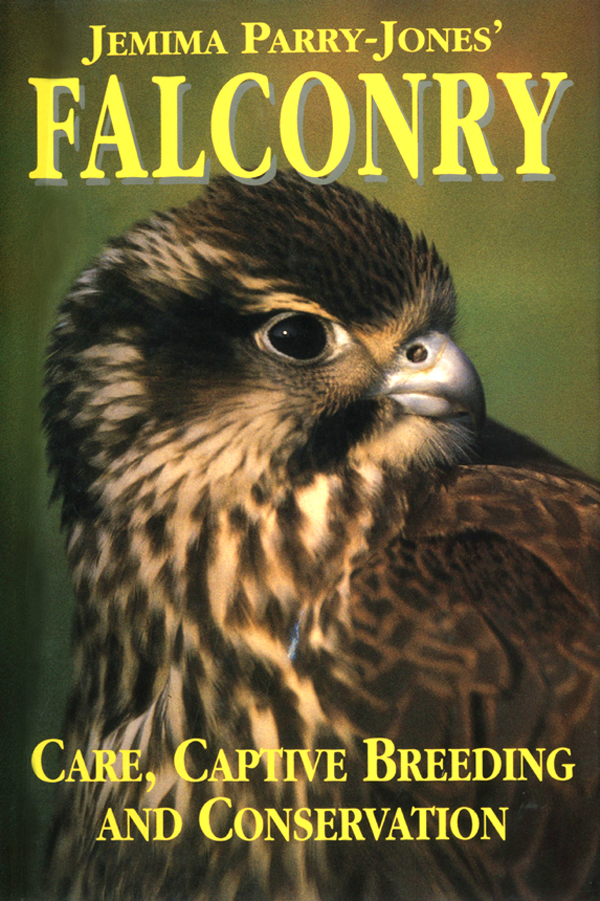

J EMIMA P ARRY -J ONES

FALCONRY

C ARE , C APTIVE B REEDING

AND C ONSERVATION

Revised edition

Danny

To Jo

INTRODUCTION

Prairie Falcon

To anyone who is interested in birds of prey, I must seem incredibly lucky to be owner of such a collection of raptors, and to have them around me at all times. While I sit in my office writing this book, I can see through the window the odd falcon or eagle flying outside, during one of the demonstrations. I can hear the cry of the African Fish Eagle and often an irate falcon calling as one of the eagles goes over her pen. If I continue writing on into the evening, the owls in their pens start calling and, more exciting, the local wild owls add their voices to the chorus. Sadly I havent heard a Barn Owl for some years, but one day they will come back.

I am also lucky in that I was asked by the publishers to write this book, rather than having to find someone willing to publish it after I had completed it. I will admit, though, that probably I would not have written it at all had they not asked me. Sitting down to write a book is a daunting task, particularly if you find it difficult to sit still for any length of time anyway, and when there are so many attractions outside that you really would much rather get on with. However, over the years I have answered so many questions, and written so many letters to people all over the world, that it really was time to save my voice, time and typewriter ribbon and put my thoughts into a book insteadso here it is.

I hope that it will answer many of those questions. It is for all those people who care passionately about birds of prey, and their welfare. It will help in the captive breeding field, whether breeding birds of prey for falconry, scientific research, captive release schemes or just for fun. It is not really a technical book on how to become a falconer, and on flying birdsthe best manual on falconry for beginners has already been written by my father, Phillip Glasier. This book should interest those who are considering taking up falconry as a sport; parts may well annoy the hell out of some people but, as a good friend of mine often says when giving me anythingenjoy!

Falconry, having remained almost unchanged for centuries, has undergone considerable changes over the last twenty-five years, for a number of different reasons. An increasing number of people are wanting to know more about the sport, and about how they can take part. Non-indigenous species of raptors which had not been used before in Britain have, over the last three decades, been imported, flown and captive bred. Some have now become more widely used than the indigenous species.

Telemetrythe use of radio transmitters and receiverswhich help the falconer find a bird should he or she become lost, have meant that birds can now be flown at a higher weight and in areas that previously were considered too enclosed for safe flying. Veterinary medicine has improved immeasurably and now broken limbs can be repaired, and illnesses diagnosed, understood and treated. Because of this, and many other factors, falconers on the whole have become a great deal better at looking after their birds. New legislation has been brought in to cover all birds of prey and falconry. This has caused large-scale changes in the obtaining and keeping of birds.

That legislation, combined with an upsurge of interest in the sport, has rendered birds far less easily available, and much more expensive. Many an older falconer will complain that he or she (and me, Im afraid to say!) can remember when Goshawks were 15 and 20 to buy. These birds are now reaching four-figure sums, although I think that the price is over-high at the moment and should drop once we get more successful at breeding this most difficult of species. Nevertheless, it should also be remembered by those people that at the time Goshawks were 20, petrol was 5/6d (27p) a gallon, and I bet that they would be pretty upset if they only got the same price today that they paid for their house twenty-five years ago! I am glad that Goshawks are no longer so accessible: the high price keeps them out of reach of many people who should not own such birds until they are more experienced falconers, and understand the different species a little better.

The most vital change as far as the future of falconry is concerned is the arrival of, and advances in, captive breeding. This means that in the long term falconry should become self-supporting, apart from the occasional addition of fresh blood for breeding. Captive breeding has, however, introduced its own problems, such as learning how to fly those birds which have been captive bred.

All these factors have changed falconry. I hope that this book will help people just starting the sport to think a little before doing so. Perhaps too, some of us who already partake could benefit from standing back and taking a good look at what we are doing.

I make no apologies for the style or the bluntness of this book. There is no intentional rudeness to any particular person; I just care greatly about my subject and about the birds.

JPJ

Newent, 1992

Black Sparrowhawk

1 THE NATIONAL BIRDS OF PREY CENTRE

The Falconry Centre was started in 1966, opening to the public in May 1967 (in 1990 the name changed to The NBoPC). My father had talked about starting a centre for years and finally, encouraged by my mother and the rest of the family, decided to have a go. I had left school and so was available, and interested enough, to help full time. We moved up from Dorset in November 66 with twelve birds. We still have one of the original inmates, a Common Buzzard called Pete. She is on loan with a friend of mine in Derbyshire and for those of you with older birds, dont despair; at twenty-one years old she produced her first babies and hatched and reared them as wellnot bad for an old lady! In those days, with no import restrictions, birds were easily available and by May 1967 we had about sixty birds. Martin Jones, now well known for his equipment (falconry wise) was at Cirencester Agriculture College at the time and used to come over regularly, collecting new arrivals at Gloucester station and helping out generally including building pens. He eventually ended up working here for some considerable time.