EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, S C D

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIB IOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIH ORT

P ROF . JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

Contents

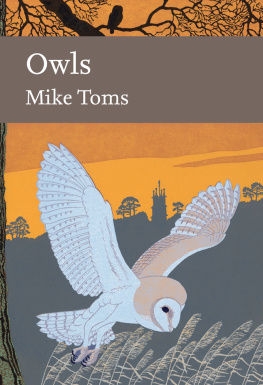

A T THE TIME OF THE FOUNDATION of the New Naturalist Series in 1943, the then Editorial Board drew up a list of possible titles, about 30 in all. Of those 30, only Owls has escaped publication until now, 71 years overdue. Over the years, several potential authors were approached, including the late Eric Hosking, doyen of bird photographers, who was Photographic Editor on that first Board and for many subsequent New Naturalists. Eric himself was long associated with owls, and indeed famously lost an eye to a particularly bad-tempered, camera-shy Tawny Owl, but sadly his intended co-author died unexpectedly and this proposal joined other non-deliveries. But all is well Mike Toms has produced a brilliant volume to fulfill this long-felt need.

For a relatively small family of birds, owls command more than their share of attention. We are all familiar with them from earliest childhood, for example in Edward Lears The Owl and the Pussycat: Lear himself was also an expert ornithological artist. Perhaps surprisingly, we admire and enjoy owls, unlike the myriad small birds that fly into a mobbing frenzy when they discover a roosting owl. On the face of it, owls could well be quite frightening, especially to youngsters. Large boldly-staring, rarely-blinking eyes never leave you, and they can rotate their heads without strangling themselves to follow your movement should you walk behind them. They do have the predators hooked beak but not as prominent in profile as a hawk and they have sharply competent and muscular talons, as any bird ringer will testify.

Historically, and all over the world, owls have been held to be creatures of magic, associates of witches (no potion would be effective without a portion of owl in its contents, as in Shakespeares Macbeth). This mystic association continues for todays youngsters in the elegant Snowy Owl Hedwig that features in the Harry Potter saga. The ghostly appearance and shrieking call of the Barn Owl, which has an almost worldwide distribution, may account for much of this association, but perhaps the Tawny is the owl at the centre of beliefs that owls are creatures of wisdom the wise old owl typified by Wol in A. A. Milnes Pooh stories and Old Brown in Beatrix Potters Squirrel Nutkin. Elsewhere, the scientific name of the Little Owl Athene noctua (introduced to England from southern Europe) is derived from Pallas Athene, the Greek goddess of wisdom. Anatomically, how an owls skull can contain its huge eyes and ears, whose highly acute functions Mike Toms details so fascinatingly as vital to their life style, can also find space for the necessary brain-power for all this wisdom remains an unsolved mystery.

Mike Toms is in the fortunate position of being an enthusiastic naturalist and also an ornithological professional, working for the British Trust for Ornithology at its headquarters at Thetford in Breckland. The BTO is world-famous for its blend of a professional scientific staff with the teamwork of thousands of expert volunteer birdwatchers who together investigate changes in bird populations, ecology, distribution and migration, both to derive scientific knowledge and to the general benefit of bird conservation. Mike notes in his introduction the role that a Barn Owl played in firing his enthusiasm when as a young paperboy on a bike he was entranced by his first sighting, which led to a life-long enthusiasm for owls culminating in this excellent volume.

Through his fluent and fascinating text, Mike Toms explores the astonishing range of differences within this small family, some of them nocturnal, some crepuscular, some diurnal, in their food and feeding, breeding biology, and migrations. For example, the Tawny Owl strangely seems to have been included in St Patricks ban on snakes, and has not colonized Ireland! The volume concludes with a chapter giving detailed accounts of each of our owl species, with mention of the various Continental and Transatlantic vagrants that have reached our shores. At long last we welcome the New Naturalist Owls by Mike Toms as it secures its rightful and valued place in our series.

I STILL REMEMBER MY FIRST close encounter with an owl. It was early one week-day morning and I was a young boy on my paper round, following a route that took me out of our small market town and into the Sussex countryside with its small woodlots and narrow fields. Free-wheeling down a shallow incline, bordered by thick hedgerows, I was surprised by a ghostly white shape that drifted through a gap in the hedge to cross the road just a few feet ahead of me. Abandoning my bicycle and my bright orange bag full of papers, I raced to the hedgerow to scramble through and catch the bird again, now quartering the field. This was my first Barn Owl, seen or heard, and I sat spellbound, enthralled by the way in which the owl appeared to float on buoyant, elegant wings. My fascination with owls began that day and continues still.

While I have been fortunate enough to be able to study owls and to document their populations through my work, it is as a naturalist that I enjoy them the most. They add character to our landscapes with their haunting calls and ghostly appearances, shape our literature and sharpen our experiences of the natural world. Very many other people share my interest in owls and, perhaps more than any other group of birds, they have a hold on us that makes them endlessly fascinating and full of character. Despite their nocturnal habits owls remain an accessible group, just difficult enough to ensure that they never bore you and that there is always something left to surprise. Birdwatchers and landowners alike delight in them, a real boon for the would-be student of owl ecology.

My interest in owls has also given me the opportunity to spend time with other researchers, many of them volunteers, who work to increase our understanding of these magnificent birds. To spend a day in the field with such people is always a pleasure and I am indebted to those who have shared their time, efforts and experience with me over the years. In particular, I owe a great deal to Adrian and Jez Blackburn, David Ramsden, Colin Shawyer, the late Paul Johnson and the much-missed Chris Mead, from all of whom I have learned a great deal, enjoyed many wonderful hours and shared the occasional flat-fly. Of course, this book would not have been possible without the efforts of other researchers, many of whom I have not met but all of whom deserve recognition for work that has increased our understanding of owls and their ecology.

The generosity of the photographers who have allowed me to reproduce their stunning work in these pages deserves special mention. To be able to use such images lifts and enhances this book and I am incredibly grateful to them all: Mohamed Bin Azzan Almazrouei, Tim Birkhead, James Bray, Richard Castell, Michael Demain, Edmund Fellowes, Paul Gale, Katrina van Grouw, Mark Hancox, John Harding, Hugh Harrop, Jo Lashwood, Dave Leech, Amy Lewis, Shay Ohayon, Jill Pakenham, Vincenzo Penteriani, Emma Perry, Gordon Plumb, Steve Round, Paul Stancliffe and Matthew Pope of the Boxgrove Project team at UCL.