SARAH A. CORBET, SCD

PROF. RICHARD WEST, SCD, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT

PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

S URPRISINGLY THIS is the first New Naturalist volume to focus on a family or group of related families of birds since Eric Simms Larks, Pipits and Wagtails published back in 1992 as No. 78. That 16-year, 28-volume drought is broken by this fascinating volume, Grouse by Adam Watson and Robert Moss.

World-wide, there are fewer than 20 grouse species, of which four occur in Britain and Ireland. Considering their relatively remote and certainly diverse habitats ranging from deep forests, through open moorland, to Scotlands highest peaks, the family is comparatively well known to all who enjoy wild places. In addition, in plumage all save the cocks of capercaille and black grouse are supremely well camouflaged, as befits relatively large, generally terrestrial and ground-nesting birds. For much of the year they are also secretive birds, the exceptions once again being the displaying cock capercaille and lekking cock black grouse.

Perhaps this combination of remote habitats, secretive habits and camouflage gives a special cachet to any sightings of the grouse family. There is no forgetting the first encounters be it of a strutting cock capercaille deep in a pine forest, of experiencing the sight (and sounds) of a black grouse lek on a frosty dawn, of a ptarmigan in mountain-top snow, or the heart-stopping moment when a red grouse explodes from the moorland heather beneath the walkers feet. Beyond that, in Grouse the authors unveil a wealth of information on the day-to-day biology and ecology of all four species, set against a global background.

Two of the four British species, black grouse and capercaille, are in worrying decline and are the subject of intensive conservation research. Another, the ptarmigan, may be an early casualty of global climatic change as the weather changes in its extreme mountain-top habitat. The last, the red grouse, as a game bird is subject in varying degrees to commercial management by man. Problems including predators, pests, disease and starvation often accompany managed animal populations and the red grouse is no exception. As valued (and valuable) quarry species for shooters, occasional controversy is only to be expected because of their commercial worth.

So despite the handful of species within the group, the variety of life styles is such that there is much to discuss for the authors, who are both international authorities on the grouse family. Their friendly familiarity with and respect for their birds shine through the text, together with their obviously deeply consuming interest and encyclopaedic knowledge, and delight in their topic. Their serendipitous meeting so early in their careers and the subsequent long-lasting collaboration have produced for New Naturalist readers a volume of exceptional scholarship and quality.

H OW WE TWO COMBINED to study grouse was a matter of chance. When aged 13, AW saw his first ptarmigan on a lone climb to Derry Cairngorm in 1943 and began to record numbers, and in the winter of 1951/2 studied them there for an honours degree at Aberdeen University. With a Carnegie Arctic Scholarship at McGill University he studied museum specimens, willow ptarmigan in Newfoundland and rock ptarmigan in Baffin Island. Returning to Aberdeen, he renewed work on Derry Cairngorm for a PhD. In 1957 he moved to Glen Esk and in 1961 to Banchory for research on red grouse, and he continued work on ptarmigan. He has studied black grouse, capercaillie and Irish red grouse, and accompanied ecologists on their fieldwork in Iceland, Norway and Alaska.

At New Year 1963, we each attended a conference in the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at Oxford. RM, who had graduated in honours biochemistry at University College London, gave a talk on fulmars of the Norwegian island of Jan Mayen, which he had visited on a student expedition. He showed keen interest in chemical aspects of the work on red grouse, and in spring 1963 came north for a study of the nutrition of red grouse for a PhD. In Scotland he has continued work on red grouse, and also on ptarmigan, black grouse and capercaillie. Abroad, he studied Icelandic ptarmigan, and rock, willow and white-tailed ptarmigan during a year based at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. More recently, he has accompanied Russian biologists in their fieldwork on capercaillie.

While writing this book, we shared a room as Emeritus Fellows of the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology at Banchory. As ever, we like arguing about grouse and studying them.

Adam Watson, Clachnaben, Crathes, and Robert Moss, Station House, Crathes, December 2006

A BOOK ON BRITISH GROUSE is timely, because recent research has clarified old problems and controversies. We offer some insights developed over two working lifetimes.

The four British grouse species occupy huge world ranges and have been studied in many countries, with millions of words written about them. We do not attempt to review this vast literature, but quote from it to give a worldwide perspective on the grouse of a small though varied corner of the globe.

Government policies can affect grouse, so politicians and others should have factual information. Grouse and their habitats are of much interest to hunters and game-dog enthusiasts, and to the many others involved in outdoor recreation. Grouse are also of great value in their own right as a beautiful part of nature. Let us care for them.

NAMES

Most authors writing in English now use the name willow ptarmigan for what was often willow grouse, and rock ptarmigan for ptarmigan. The name red grouse is so well known that it would be confusing to call it willow ptarmigan. We use willow ptarmigan for races other than red grouse, and Lagopus lagopus for red grouse and willow ptarmigan together. For brevity we write ptarmigan when a section is clearly on rock ptarmigan. We use the old names blackcock and greyhen, and blackgame for both sexes of black grouse.

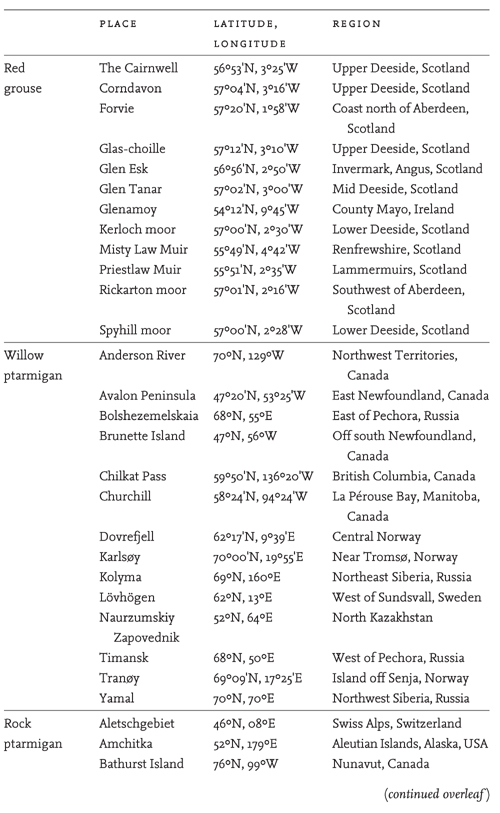

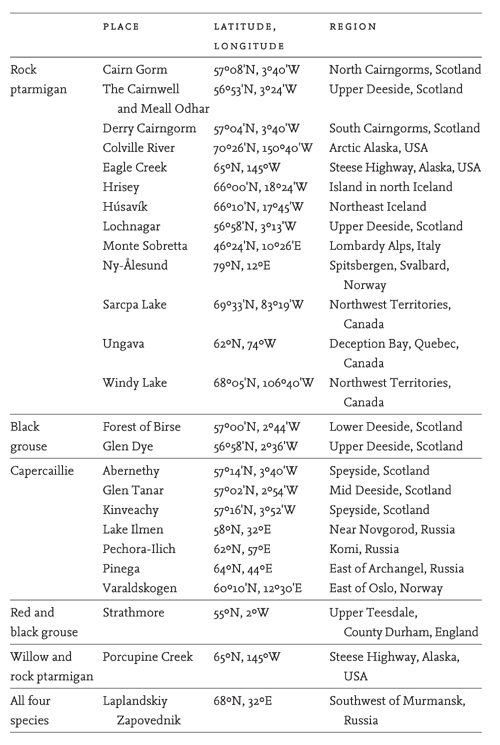

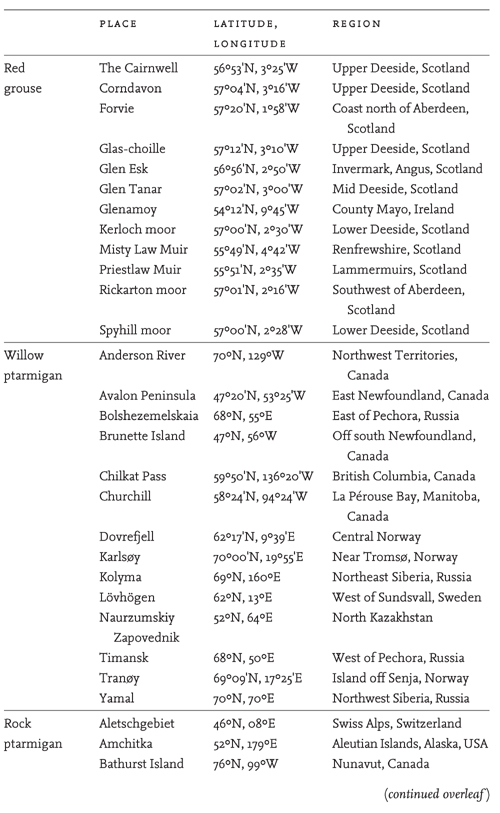

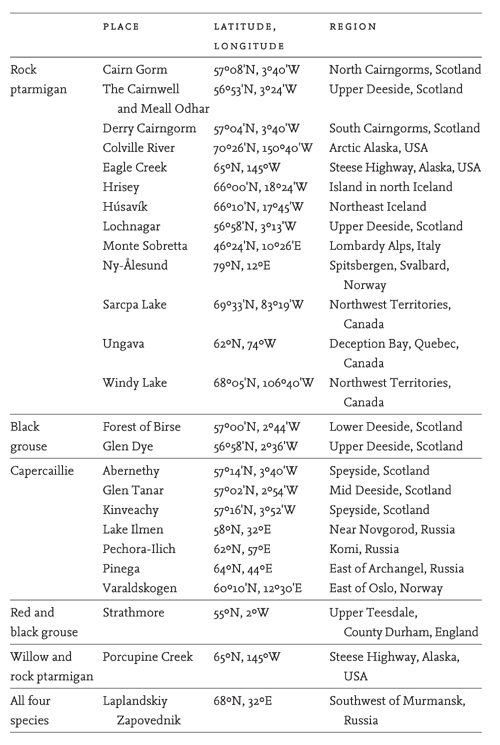

Distribution maps are readily available elsewhere (see Bibliography), and so we do not give them. Table 1 lists the main study areas mentioned in the text.

TABLE 1. The main study areas mentioned in the text.

CHAPTER 1

Grouse Worldwide

ORIGIN OF SPECIES

G ROUSE ARE LARGE BIRDS adapted to cold. Creatures of the northern hemisphere, they live in Arctic, boreal and temperate regions, and spend the winter in northern or mountainous habitats without migrating south as many other birds do. They subsist on low-quality but abundant foods such as woody shoots, catkins, buds, twigs, bark and conifer needles.

Molecular evidence shows that the ancestor of all grouse diverged from turkeys of global cooling, when new habitats such as boreal forest and tundra replaced more tropical vegetation in northern regions. This opened a new niche for large birds that could survive on coarse foods through long, cold winters.