Copyright 2003 by Dennis Walrod

Published by

STACKPOLE BOOKS

5067 Ritter Road

Mechanicsburg, PA 17055

www.stackpolebooks.com

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to Stackpole Books, 5067 Ritter Road, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055.

Printed in the U.S.A.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

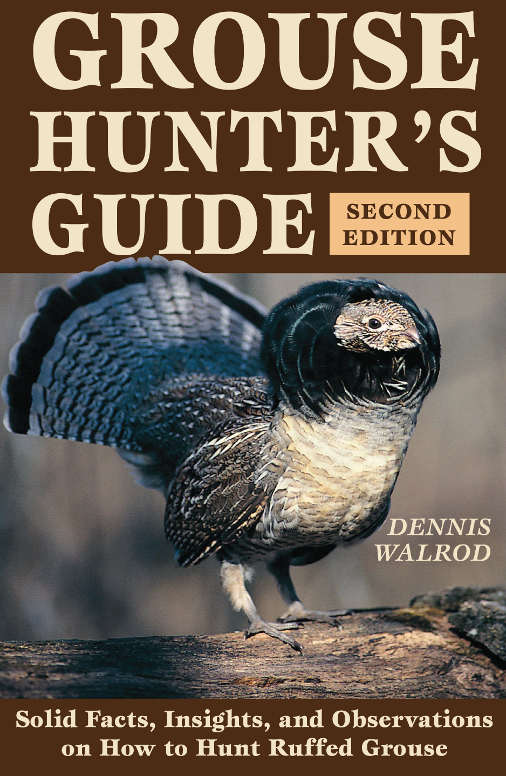

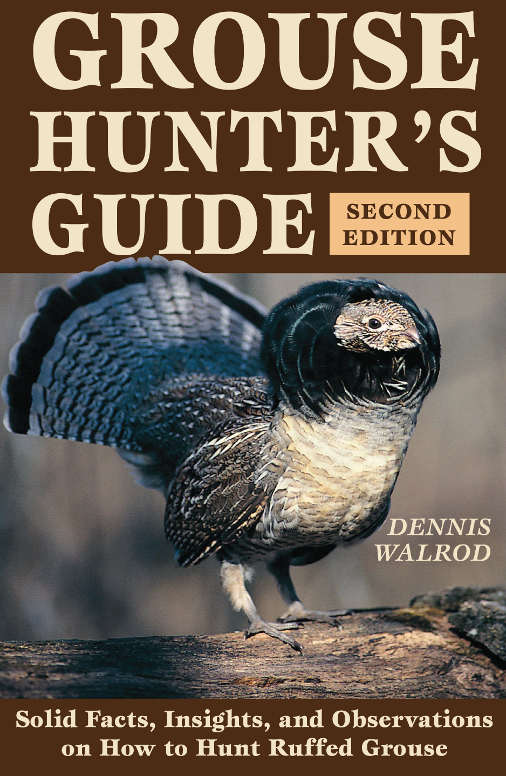

Cover photograph by Bill Marchel

Cover design by Caroline Stover

All photographs are by the author unless otherwise indicated

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Walrod, Dennis.

Grouse hunters guide / Dennis Walrod.Expanded and rev. 2nd ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-8117-2889-7 (pbk.)

1. Grouse shooting. I. Title.

SK325.G7W35 2003

799.2463dc21

2002156625

ISBN 978-0-8117-2889-8

eBook ISBN: 9780811743020

This book is dedicated to the ruffed grouse that get away, the ones we miss and sometimes swear at.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to Ken Szabo of the Loyal Order of Dedicated Grouse Hunters for so generously providing the 20012002 hunter research data that is presented in this book. The insights into real grouse hunterdom (gun, gauge, and dog preferences; covert ratings; and annual kills per season), gleaned from the logged data of several hundred dedicated LODGH members, have been immensely useful to my writing. If it were possible, I would invite every one of those contributors of grouse hunting wisdom and experience to share my favorite coverts.

I want to express gratitude to Tom Martinson, freelance wildlife photographer, for the many excellent photographs of wild ruffed grouse that grace these pages. My appreciation is also expressed to the Ruffed Grouse Society for permission to borrow a paragraph here and there from articles of mine that had earlier appeared in The Drummer. And I thank all the major grouse researchers of the last century (notably Gordon Gullion, John Kris, and of course, Gardiner Bump et al.) for their contributions to our understanding of upland huntings greatest gamebird.

In this new century, I am greatly appreciative of the contributions of the Appalachian Cooperative Grouse Research Project, which is continuing to produce discoveries that are vitally important to the future of our sport. I would firmly and warmly shake the hand of Gary Norman, the coordinator of the ACGRP six-state project, for his very helpful advice and guidance via e-mail. I also thank Tom Allen, who got me off to a good start with the ACGRP, and I am, as the clich goes, eternally grateful to Todd Fearer for the wonderful composites of habitat and radiotelemetry of grouse wanderings that he has produced. Now, thanks to him, we have a material definition of a grouse covert!

Without the thoughtful and cooperative assistance of certain hunting partnersRick Sanders, Bob Ungerer, Howard Roche, George Videll, and Stephen Hookwho were each deputized at various moments to stop in their tracks either to be photographed or to do the photographing, I wouldnt have been able to illustrate this book with the authentic actions of real grouse hunters.

A DIFFERENT SORT OF HUNTING SPORT

The essence of grouse hunting, including the allure and the mystique, the beginning and the end, can be described in a scenario that often lasts less than five seconds.

First, the stage setting. You are amidst the tangled glories of an autumn covert where grouse are known to lurk. Something very special is about to happen; an unidentified instinct tightens your grip on the gun. Even though you have just passed a myriad of interesting brush piles, pricker bushes, grapevine festooneries, and other grouse haunts without incident, this next place seems different. Maybe the songbirds are suddenly quiet, a clouds edge may have crossed the sun, or perhaps the dog has assumed a stiffened gait and slowed his speed. The ground under your feet seems to lose stability, as though your next step might trigger a trembling that would alarm the woodlands and shake you into awkwardness. The gift of total awareness begins to glow from within as though a rheostat had been twisted to full ON. The reality of the present instant becomes starkly intense. We are talking magic here. Clarity and purpose now replace autumnal daydreams. You take another step and then another; your body is not listening to your mind.

Then it happens. Thunder erupts, a sound so wild, so thrilling, that the human heart swells to embrace it. A ruffed grouse is in the air, blurred wings clawing against the sky for more air, more speed. Seldom are you privileged to know the exact spot from which it sprang, this phantom, this grouse, this elusive target. The gun, featherlight only moments ago, becomes heavy and slow to move. Time also slows down. Your mind records what happens next with great clarity, while your body protests that theres not time enough to swing the gun accurately and purposefully along the path that the grouse is slashing and tearing against the backdrop of an autumn sky. But somehow, your hunters reflexes take control, overriding thought, and you make the guns muzzle transcribe a neat, quick arc that first follows and then catches up with that source of thunder. The gun fires new lightning. There is shock, a momentary glimpse of wings suddenly folded, and then the bird plummets. You feel a surge of elation, then a flicker of sadness, but it doesnt last long. A ruffed grouse has been downed.

In your minds eye, the world resumes turning, clouds commence drifting, and the moment of expectant stillness from which brief violence sprang is over, once again. You will remember the event, as all grouse hunters do, for a very long time.

Every grouse flush is different from all others. We might, along the way, permit some of our misses to fade from memory, but successful hits are always there to recall. And so will be that strange feeling, remembered now, that you positively knew something was about to happen.

Several brushworn grouse-hunting buddies and acquaintances have, over the years, spoken to me about a feeling of expectation, a sense of great certainty that often precedes their observation of a ruffed grouse suddenly in flight. These hunters were, one and all, embarrassed to reveal this feeling, as though they were confessing a hidden belief in flying saucers. I understand their embarrassment; one does not comfortably mix metaphysics with natural science.

There have also been times when that feeling has come upon me, yet no grouse has flushed, nary a one. I have, on these occasions, accused myself of playing mental games under the guise of wishful thinking. No other creature I have hunted uses the element of surprise to such a highly developed extent. One, maybe two seconds pass, and the bird is gone; the woodlands are again silent.

I have taken nonhunters into the woods, people who never would have ventured there otherwise, and we have occasionally flushed grouse. My eyes would automatically observe much detail of a flight, the birds direction, sometimes even the glitter of its frantic eye and the color phase of the feathers. My neophyte partners might then exclaim something like What made that sound? or What? I didnt hear or see a

Next page