Copyright 1998, 2003, 2015 by Stephen J. Bodio

Introduction copyright 2015 by Paula Young Lee

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

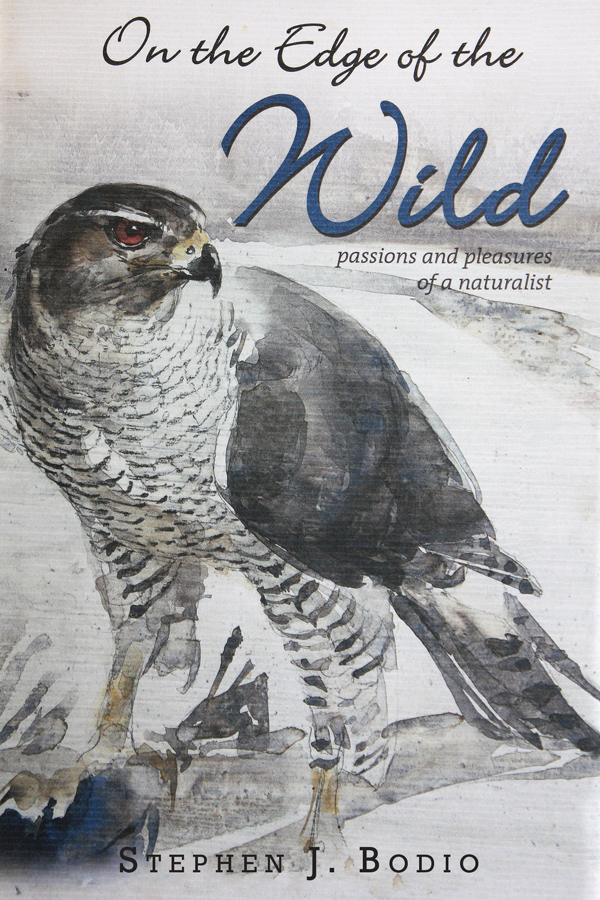

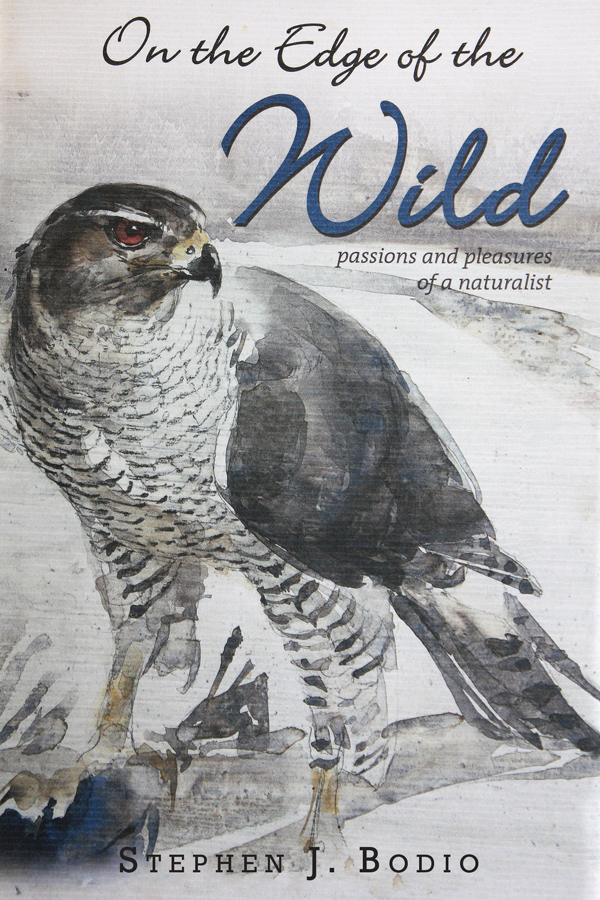

Cover illustration courtesy of Vadim Gorbatov

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-711-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-076-1

Printed in the United States of America

This, like his books, fuselage, imaginary garden, family, loves, religion, and private history was an indispensable component of the spiritual survival multiple he was inventing for himself, and through which he intended to sandwich himself between earth, sea, and stars with the fit a waffle has within a waffle iron, or the kind of mortising James Powell had performed in his skiff, less a seamlessness than the kind of laminated strength a scar has.

Thomas McGuane, Ninety-Two in the Shade

Books by Stephen Bodio

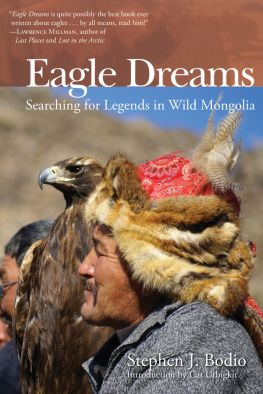

Eagle Dreams

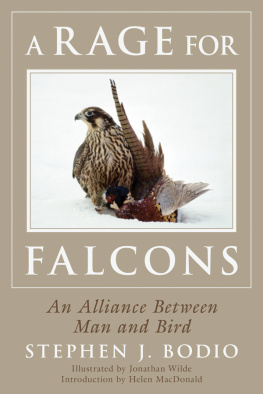

A Rage for Falcons

Good Guns

The Art of Shooting Flying

Aloft

Querencia

Good Guns Again

On the Edge of the Wild

Contents

Introduction

I dont think anyone can love anything without knowing it very well, writes Stephen Bodio in the opening to this collection of his essays, On the Edge of the Wild: Passions and Pleasures of a Naturalist. Eloquent in their honest acceptance of lifes complexities, these essays do not seek to explain what love means to him, or what it could mean to someone else. Hilariously funny and poignant in turns, Bodios writing embraces the paradoxes of loving nature in a data-driven world. He doesnt have all the answers. More importantly, he doesnt pretend to.

Avoiding pretenses is harder than it seems. Being open to difficult questions is harder still.

Man is the only animal that laughs or weeps, wrote British critic William Hazlitt in 1819 , for he is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are, and what they ought to be. It is easy enough to condemn a wretched world, to speak ill of the dead, to cast aspersions into the wind. But the conundrum faced by the animal-who-laughs has always been the second partdeciding how things ought to be. Which changes would remedy the ordinary cruelty of everyday life? Would it be a good thing to bring an end to all suffering... no more sickness, no more death? Are we speaking just of humans here? What of the suffering of animals, the sickness of plants, the killing of germs? What ought to be (or not to be)? That is the question, for my version of a perfected world is perhaps not yours. Thus there is laughter at our mutual delusions. And weeping, for we shall never be reconciled.

For centuries, humans have searched for the clavis universalis, the universal key that explains, well, everything. The secular incarnation of God. The trouble with the clavis universalis is that its not just a futile quest. Its a metaphor. It summarizes an obsession with a better world that would open up if only we had a key. (To lock us into an invisible prison, or to escape from it?) Either way, it would include a state of permanent bliss free of pesky responsibilities. No more unpaid bills, broken hearts, flaky dandruff, or ungrateful children. Such shining visions can only be defended by knowledge that is perfect, complete, and eternal, but for the same reason admits no error and tolerates nothing that falls outside its rubric. This is the story of Goethes Faust, and the lesson taught by the Devil: an angel cast out of heaven for challenging the Almightys word. A tragicomedy, Faust tells the tale of a scholar who has spent his life studying all there is to know and yet is tormented by his limits. He makes a deal with Mephistopheles. The devil. The one who refuses to take God at His say-so. The devil forces Faust to confront archetypes of good and evil, heaven and hell, the spirit and the flesh, by introducing him to Woman. And it is in love that Faust falls... in more ways than one. A tragedy.

In the sequel, Faust regains his immortal soul. A comedy.

For the past two centuries, the lonely hunt for the clavis universalis has been replaced by the collective march of civilization. The civilizing process has little to do with a seekers quest for deep understanding of lifes large questions. Instead, civilization offers creature comforts to those who abide by its rules. It endorses the technologies of domestication, all of which provide an appealing illusion of control. Civilizations mascot is the pet dog, a formerly wild animal bred to serve human whims and trained to obey his master, all the better to lick the hand that feeds it.

Inside this cultural framework, the new Fausts are seekers of knowledge who insist on doing it the hard wayby going straight to the original source. They are ardent lovers of the wilderness and hunt the land for the kind of sustenance that feeds both body and soul. For to hunt is far more than murdering wild mushrooms and tracking wild animals. It is to search for answers that go beyond other peoples conclusions. It is to get both hands and feet dirty, to walk into the fray of the unknown, accept the Devils challenge, and risk falling into love with the fierce, unpredictable, sensuous, violent, fertile, and sublime seductress that is Nature.

Today, we teeter on the edge of a new world where wildness is more elusive than ever. It is thus as a newly urgent collection of meditations on this rapidly disappearing state that Bodios On the Edge of the Wild is now being republished by Skyhorse Publishing. As a group, these well-edited essays reveal a rare authenticity of feeling that ultimately binds them together. Bodio calls the resulting group a collage. I call it essential reading. A literary memory box, let us say, as well as an intimate manifesto on the importance of love.

Bodio loves the women in his life. He loves his hunting dogs too, gives them names like Spud, and Bart, acknowledges their individualism, and indulges their quirks. Dogs, he writes, will always present you with problems, conundrums, solutions. (?). We impose on Nature, and she kindly puts up with us. From Bodios essays, we grasp a gentle message. Distilled, it is this: we are not animals. Animals are not us. This difference doesnt make us better. It doesnt mean theyre less.

The exceptional pleasure of reading this collection derives, in part, from Bodios ability to distill the ineffable qualities of a hunt into a few minimalist lines. But it is his unique perspective on the ties that bind the living land to the people who seek to understand it, which makes his writing on the ancient practice of falconry the strongest essays in this collection. With a gimlet eye, he evokes his lifelong fascination with these marvelous birds, a fascination explored at length in several monographs which have now become contemporary classics (Eagle Dreams, A Rage for Falcons). Never seeking to minimize the raptors essential alien-ness, he stresses that the negotiation between a trained falcon (which are often preferentially female) and her human requires mutual patience. In one of the best essays, ) To fly a goshawk (or a peregrine, an eagle, a gyrfalcon, or any other raptor) reveals human priorities, but tells us nothing about what the bird thinks.

Next page