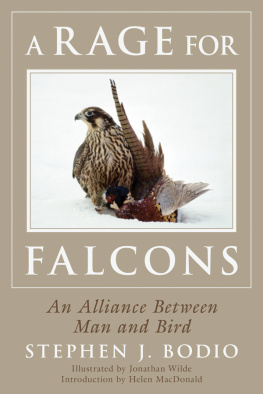

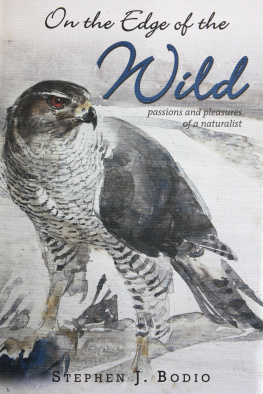

Copyright 1984 by Stephen J. Bodio

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2015

Introduction copyright 2015 by Helen Macdonald

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Interior design by Joe Freedman

Cover design by Jane Sheppard

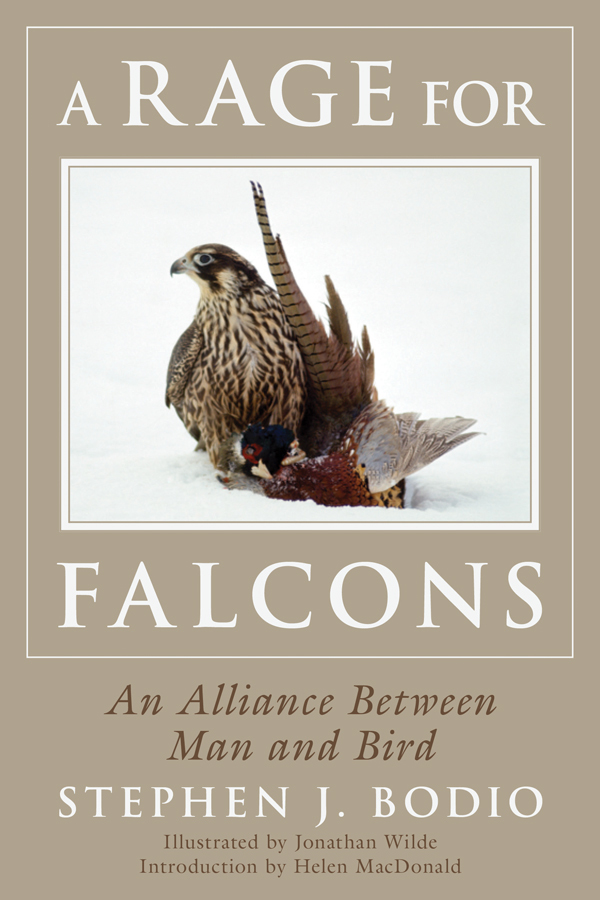

Cover photo courtesy of Michael Quinton

Print ISBN: 978-1-63450-672-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63450-949-7

CONTENTS

To Betsy, of course,

for everything

First the hawk, then the horse, then the hounds, then, and only then, the humble falconer.

Anon.

Falconry is not a hobby or an amusement: it is a rage. You eat it and drink it, sleep it and think it. You tremble to write of it, even in recollection. It is, as King James the First remarked, an extreme stirrer-up of passions. Every falconer who reads this book will write angry and contemptuous letters to me, calculated to laud his own abilities and to decry mine.

T. H. W HITE ,

The Godstone

and the Blackymor

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Id like to thank all the falconers and others who have helped me through the years. Ralph Buscemi deserves special mentionI was his apprentice, and learned how to do it right from him. Mark Fanning gave me Cinnamon, and Tom Ricardi bred Gremlin. Bill Satterfield, veterinarian and falconer, cured my birds when they were ill. Cornell University brought back the peregrine, and John Tobin was my project partner, telling war stories on the mountain. Harry McElroy taught me how an accipiter thinks, if thinks is the word, and was a gracious host in Nevada. Charles Schwartz showed me his breeding project, and told me tales of sage grouse. Jim Skidmore, master long-winger, taught me the secrets of waiting on. Kent Carnie gave me hours of good talk and valuable historical insights. Any errors or opinions in this book are mine alone; its virtues owe everything to my friends. To all the above, and all not mentioned, good hawking!

And a special thanks to Jon Wilde for the perfect illustrations, to Nick Lyons for being the kind of editor that I thought had vanished, to Ed Gray and his Journal for support, and to Betsy for more than typing.

Magdalena, New Mexico

1983

INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 EDITION

When this book came out, I was twenty-two years old; a scruffy literature graduate whod flown hawks for years. My two great loves were falconry and literature. They lived at the opposite ends of my life and barely touched. I had a vast library of falconry books, and they came mostly in two kinds: dusty antiquarian tomes or modern how-to manuals. When I bought a copy of A Rage for Falcons I assumed it was the latter, and opened it expecting the dry voice of the self-professed teacher. But it wasnt there. Instead, a kestrela five-ounce, helicoptering, cow-pasture bug hawkdescended from the sky to the authors baited trap.

Blam! Reading those first few pages I was caught as fast as that kestrel and was just as surprised. For this was the real thing. It was a book by an expert falconer who could write like an angel. A Rage for Falcons taught me that modern falconry books could be literature, and it inspired me to try one day to write one too. This is not a book about how to train a bird of prey. It is something much rarer, richer, and better. If youve ever wondered what falconry feels like, what it is like to gain the trust of a wild hawk, train it, watch it fly, hunt and return to you, this book will show you. But be warned: its heady stuff.

A Rage for Falcons comprehensively skewers the common assumption that falconry involves oppressing or subjecting wild birds to your will. That is not what falconry is about, and it has never been so. Back in early-modern Europe, falconry was associated with the ruling classes partly because it was expensiveback then a good falcon could cost as much as half the yearly income of a knightbut also because it was a visible display of ones ability to govern with wisdom, rather than relying on brute power to achieve your ends. Everyone knew that a mistreated hawk would fail to fly or be lost, so a good hawk was a testament to your patience, understanding, and negotiating skills. The falconers role, wrote seventeenth-century falconer Edmund Bert, is to provide for all your hawks needs, and behave in ways that make your hawk love you. Wise falconers will always tell you that hawks are not pets. The end-game, writes Bodio, is always as close to wildness as possible.

What of its author? You might have come across Bodios elegant book reviews in Grays Sporting Journal, his superb books on pigeons or eagles. You might have read Querencia, his great and moving meditation on love and loss and home. But if Bodio is new to you, then know that the book you are holding is by one of the great modern sportsman-naturalist-writers. Soon after meeting him Annie Proulx realized that here was a man vastly well-read in history, paleontology, archaeology, climatology, who knew about ancient horses, the history and habits of the dog, Egyptian mummification processes, could quote from Buffon, Charles Wilkes, William Bartram, Wilfred Thesiger, and the authors of little-known treatises on gyrfalcons and eagles. Bodio is all those things, and more. Sometimes he seems a visitor from the nineteenth century, a traveler from a time when a deep knowledge of literature, history, the natural world, and our intimate relation with it through hunting, observing, collecting, and animal-keeping were considered signs of rare humanity rather than eccentricities. But he is also modern as hell. Bodio might keep ancient breeds of hunting dogs and falcons, but A Rage for Falcons could not have been written at any other time. It is about falconry, yes. But it is also about a particular time and place in America. Suffused with the tang of sagebrush and the hush of snowy east coast woods, it reads like some wondrous hybrid of Tom Wolfes The Right Stuff and Aldo Leopolds A Sand County Almanac.

In prose that moves from gentle informality to hell-for-leather gonzo virtuosity, Bodio vividly recollects flights and the shifting weather of forest and open country. He pleats science with history and anecdote, moving fearlessly across time and spaceone moment dramatizing a hawk-trappers set up in nineteenth-century Holland so vividly you feel you are there, the next writing with wry humor of the aching boredom of sitting in a hide in thin rain waiting for hawks that never come. He is wonderfully honest about the frustrations and difficulties of a sport that can bewilder you, horrify you, perhaps even injure you. And his raptors will never leave you. He captures not just the appearance of the different species used in falconry, but their essential moods and palpable otherness. A trapped sharp-shinned hawk whipping around in the box in a kind of insectile fury like a predatory butterfly. A falcon ruffling her feathers to look like a dry pine cone, or burning low over the landscape as if she were jet-assisted.