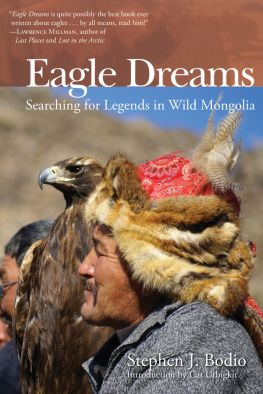

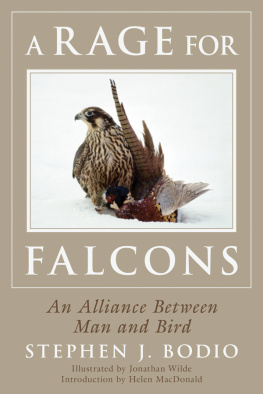

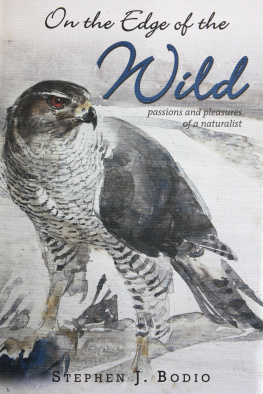

OTHER BOOKS BY STEPHEN J. BODIO

On the Edge of the Wild

Querencia

Aloft

Rage for Falcons

Copyright 2003, 2015 by Stephen J. Bodio

Introduction copyright 2015 by Cat Urbigkit

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

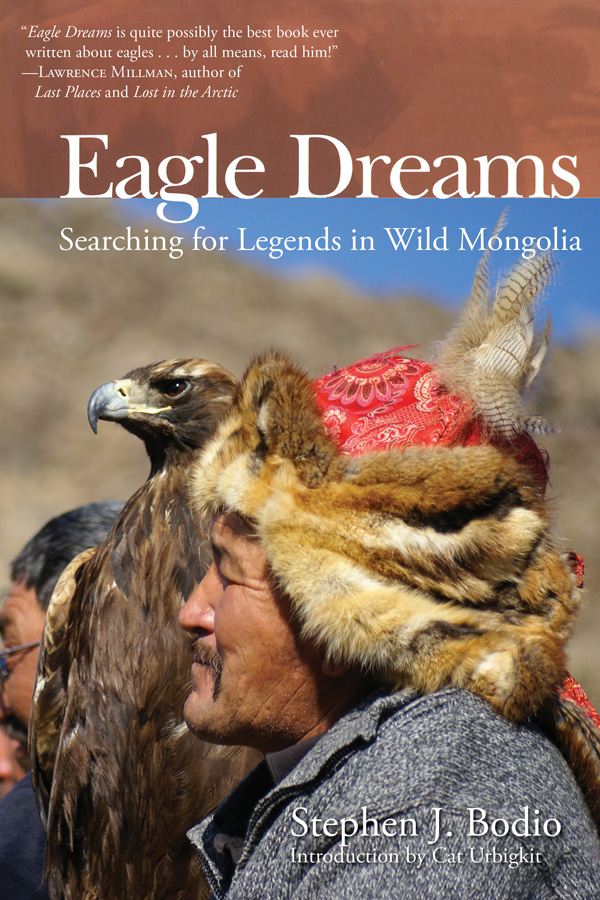

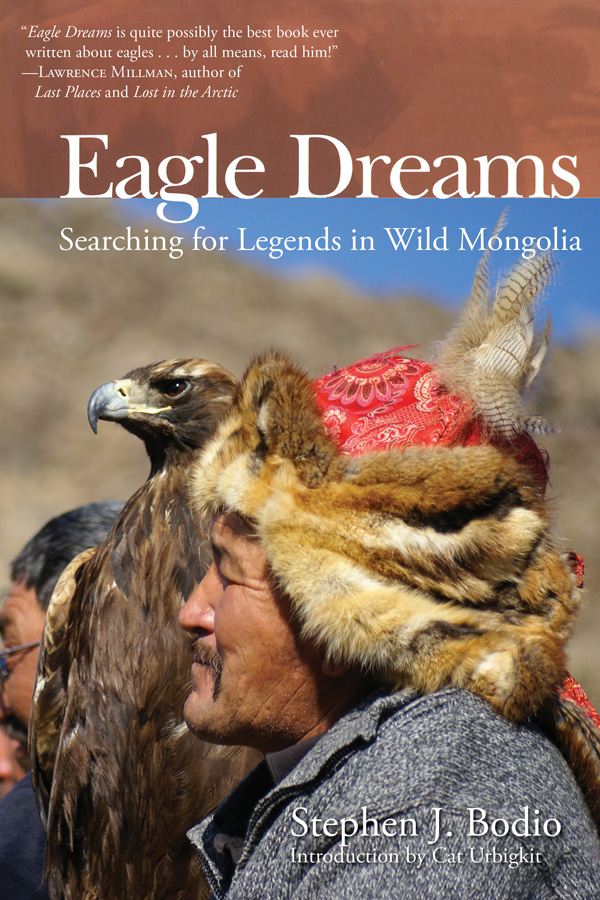

Cover photo courtesy of Cat Urbigkit

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-479-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62914-929-5

Printed in the United States of America

To Canat Cheryiasdaa, guide, soldier, ever-cheerful

companion, friend;

and for Libby, who once again made it easy

Life has not stopped and the world is not really a museum, yet.

Ted Hughes

The beginnings of my own journey did not lie in scientific study, nor was I sent on a mission or expedition of any kind. I came to it more in the way of an old man dreaming a dream or a young man seeing a vision.

Owen Lattimore, The Desert Road to Turkestan

A UTHOR S N OTE

Recently I read an item in Atlantic Monthly where it was alleged that those who went on difficult trips and wrote about them were now called explornographersderivation self-evident. Honni soit qui mal y pense , but I hope this book offers a bit more than titillation.

My flying visit begins in libraries and photographs, rambles around in memories, goes to Brooklyn and Wyoming, to New Mexico, and to the New England of my youth before it ever leaves the States for an exotic place. It is a little bit about moving around in time, but, though it contains facts about faraway places and strange animals, it is not just about moving through space. If you want straight narrative, Id suggest you skip forward to Part II.

On orthography: there is none, yet. My friend Canat, who speaks five languages, spells his wifes name two ways and the name of the town where he lives in three. Our friend spells his name Aralbai, but another book spells it Orolobai. A biologist of my acquaintance spells his name Munkhtsog, but still another book spells it Montsukh. I even know a businesswoman who spells her own name two ways. And thats without getting into historical (i.e. nineteenth century) spellings. Mongolia has several languages, and has had three scripts. I merely attempt to split the difference.

In order to make the narrative more comprehensible and less repetitive, I have altered and shortened the time line and the order of the in-country section a bit. Nothing significant has been omitted.

Stephen J. Bodio

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

Its a faded image that flickers in your mental background for eternity, at times rising to the surface, causing your nostrils to flare as a primal memory brings forth the aroma of mutton cooking over a fire fueled by sweet-smelling dung. You are transported to that place, hearing the gentle murmur of air pushed by powerful wings as the shadow passes overhead, and you reflect in the amber light of the Central Asian steppe.

Steve Bodio captures the essence of those whose eagle dreams are answered on the wild steppes half a world away. Eagle Dreams takes us to the place where falconry cultures have their originthe ones that seem to descend unbroken from the time when horses were tamedwhere mankind came riding out of the steppes of Central Asia with an eagle perched before him in the saddle.

Most of my winter days are spent under the always-watchful gaze of golden eagles that migrate to western Wyoming rangelands from more northern climes. Golden eagles contain power and intelligence in a body that weighs only twelve pounds, Steve writes in Eagle Dreams. They can appear and disappear like magic in seconds, fall out of the sky to kill a hundred-pound antelope or a five-pound flying goose with no tools, only the muscles of a hollow-boned body smaller than a childs.

Long intrigued by these aerial wolves, I imagine the journeys that draw them to Wyomings winter landscapea harsh place in its own right. That captivation eventually pulled me from our Wyoming ranch, following the trail blazed by Steve years prior, leading me to Mongolias western Bayaan Olgii region.

I liked Olgii as soon as I saw it from the air, arriving in one of the twice-weekly flights of a crackling and groaning 50-seat turboprop Fokker 50. Situated along braided river corridor in a mountain valley, Olgiis nearly 30,000 inhabitants are scattered among adobe houses and surrounded by gers, the felt-covered portable structures known to most Americans as yurts. Driving to town from the airport, we swerved around yaks walking untended down the road or being driven in small herds by men on horseback, saw large red ferocious guard dogs on chains in ger yards, and cattle eating from piles of burning garbage alongside apartment complexes.

When I stepped into Steves friend Canats office in Olgii, there was Eagle Dreams the book that had served as my compass on this journeydisplayed prominently on the table, a visual acknowledgement that Steves eagle dream had come full circle. Canats fledgling guide service handled the logistics for my own eagle journey, providing a charming young interpreter, a shy but good-natured cook, and a jolly Mongol driver to serve as support for friend Janell and I as we joined a group of Kazakh eagle hunters on horseback for an excursion across the steppe and a glimpse into the regions rich culture.

Quickly leaving paved roads behind us, we traveled in a Russian Land Rover-type four-wheel drive for most of the afternoon, bouncing across the countryside, following barely discernable trails along river bottoms and over rocky passes before finally arriving at the creekside ger of Aralbai and his family. In keeping with both local tradition and common sense, our driver rolled down the window and called out the English equivalent of Hold your dog. Within seconds we were whisked into the warm and roomy family ger and I was engulfed in a bearhug by Aralbai and introduced to his family members. Steves portrayal of his old friend was spot-on: this backcountry Kazakh cowboy was as tough as the rocks of his Altai Mountains.

In Eagle Dreams , Steve describes Kazakhs as the people who once had conquered the area from the Altai to the Black Sea, then washed back and forth through Central Asia, riding with their cousins the Mongols under Chingiz, splitting from their oasis-dwelling kin, the Uzbeks, in the fifteenth century, then more recently from their fellow nomads, the Kirghiz. Disregarding boundaries, fleeing city-states ancient and modern, they had fetched up again in their ancestral mountains, where their legends tell that they were born of a mating of a man with a she-wolf.

In the ger, a low table was pulled out of its cove and huge platters of steaming goat meat, rich yellow potatoes, onions, and cabbage were piled on, along with bottles of vodka, cups of hot tea, and the fermented mares milk drink called airag. The ger was crowded and noisy with festive conversations in English, Kazakh, and Mongol.

Next page