Slow Boat to Mongolia

Lydia Laube resists jet planes and tourist destinations, firmly believing that the journey is the thing, not the destination. Seen often in China clutching a ticket and hopping on a train hoping it was the right one, Lydias single-minded determination and enthusiasm invariably carries her through. A nurse by profession, Lydia has delivered babies and tended clinics all over the world. And growing up on a farm in the mid-north of South Australia made her no stranger to mutton, a distinct advantage to a traveller visiting Outer Mongolia.

Slow Boat to Mongolia is Lydia Laubes third book. Her first two, Behind the Veil: An Australian nurse in SaudiArabia and The Long Way Home, have been Australian best-sellers.

Slow Boat to Mongolia

LYDIA LAUBE

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

Australia

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 1997

This edition published 2010

Copyright Lydia Laube, 1997

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Designed by Nick Stewart, design BITE, Adelaide

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Laube, Lydia, 1948

Slow boat to Mongolia.

ISBN 9781862549005.

1. Laube, Lydia, 1948 Journeys. 2. Mongolia

Description and travel. 3. China Description and travel.

I. Title.

915.17304

contents

By the same author

Behind the Veil

Bound for Vietnam

Is This the Way to Madagascar?

Llama for Lunch

Temples and Tuk Tuks

The Long Way Home

The Sunday evening crowd relaxed at the waters edge of the Darwin Yacht Club. A full tropical moon, fiery red, rose up out of the sea and turned to gold as we talked idly of places and people. Somebody was talking about Outer Mongolia. My attention was riveted. Outer Mongolia! What a mystical pull those two small words had.

Id like to go there, I said.

Nobody goes there. The voice sounded gloomy, detached.

Why didnt anybody go there? How tantalising. It was as if my fate were sealed in that moment. I knew at once that I could not resist. Go there I would and just as soon as I could arrange it. I could make my long-planned visit to China, a place I had wanted to see since the days when it had been closed to travellers, and try to reach Outer Mongolia from there. Once, when I had been working in Hong Kong, I had travelled to the border so that I could say that in some small way I had seen China. It had been just a tempting few steps away but, later that day, in the same place, five Hong Kong policemen had been killed in a fracas with their communist neighbours. I did not go back.

Despite starting with only vague ideas about Outer Mongolia a remote exotic place, at the end of the earth, where dashing wild men galloped their brilliant horses across limitless steppes I soon put my hands on everything that had ever been written about it. Few westerners had visited this little explored place and to go there would make me a pioneer, one of the first.

Outer Mongolias communist portals had only recently been opened, just a crack, to allow selected tourists through. The major obstacle was a visa, a favour the Mongolian authorities confer with great reluctance on decadent capitalists travelling independently. Visas were only issued on an invitation from a Mongolian, and not knowing a lot of Mongolians prepared to invite me, all my enquiries in Australia came to a dead end. Then I heard that the elusive visa might be obtained in Hong Kong or Beijing. That would do me.

I also read that Mongolia was a traveller, not a tourist, destination, and only for hardy, adventurous people who were not averse to a diet that was almost exclusively mutton. This posed no threat to me. I had been raised on it.

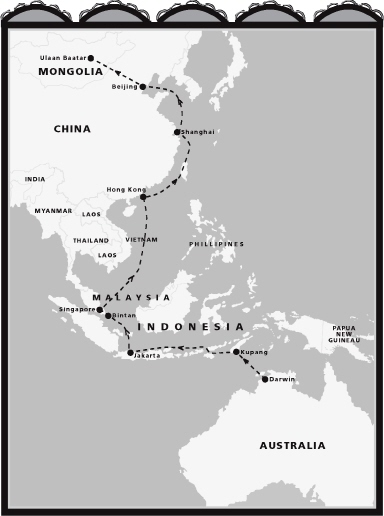

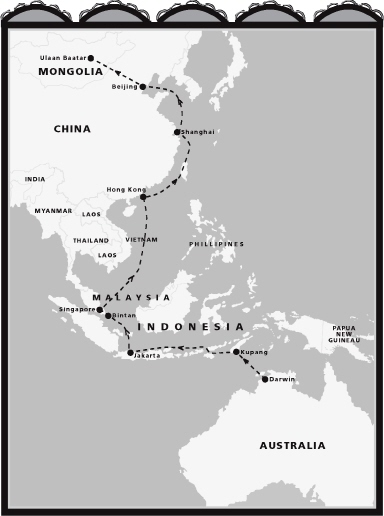

Out came the map. I would travel in my preferred manner: by sea and land. It looked easy: I could take a short sail over the Timor Sea to Kupang in Timor, hop from island to island up the Indonesian archipelago to Singapore by inter-island boat, find a vessel plying between Singapore and Hong Kong that would have me on board, take the ship that sails regularly from Hong Kong to Shanghai, and then travel by train, on the Trans Siberian Express, as far as Ulaan Baatar, the capital of Outer Mongolia. It sounded simple.

My research into sailing from Australia revealed that the only hope of a commercial passage out of Darwin was to Bali or islands west on one of the occasional cruise ships. Such an exercise requires about two hundred dollars a day and dressing for dinner every night. Other highlights are afternoons spent in the hairdressing salon and being taken ashore at ports of call to view the locals, who are flashed past the air-conditioned bus provided for the inspection tour like exhibits at a sideshow. Mentally flipping through my travel wardrobe of three shirts and two pairs of pants, I decided it was not for me. I would suit Indonesias Pelni ships better. All I had to do was to get to Kupang to connect with one.

There is a twice-weekly plane from Darwin to Kupang, but the airline concerned was not one I would fly with by choice. During the dry season in Darwin it is not difficult to find passage or work on yachts, many of which are heading north to Asian ports. I advertised on notice boards where the boats moor and got many offers, probably thanks to the joker who altered my ad from, Female requires passage to Kupang working or paying, to Female requires passage to Kupang working or playing! They are an uncouth lot in the Territory, which is probably why I like them. I was offered legitimate rides to Africa, the Cocos Islands and Perth, and the gypsy in my soul found it difficult to refuse. But Outer Mongolia was my goal.

Not long afterwards I was enjoying another Sunday evening at the yacht club. Dusk was settling over the tide coming in across the sand flats as I sat down at one of the wooden tables on the edge of the small cliff overlooking the beach. A man at the other end of the table was gazing out to sea. After a while he turned around.

Not bad is it? I said.

Blood oath. This enthusiastic reply came from Doug, a smallish man, not young but deeply tanned and, from what I could tell, very fit. He told me he had sailed to Darwin from Papua New Guinea to compete in the world-famous Darwin to Ambon boat race.

Having watched the start of the race the day before, I felt qualified to pass judgment on his plans.

Next page