Wakefield Press

The Long Way Home

Lydia Laube was born on her familys farm in the mid-north of South Australia. She was blessed (or cursed) at birth by a passing fairy, who left her with itchy feet and insatiable curiosity. After completing nursing qualifications in Adelaide, she crammed her belongings in a VW beetle and set off to see the world. In twenty-five years of nursing, Lydia has delivered babies on her knees in New Guinea, tended clinics in dug-out canoes in Papua, worked on a junk in the Hong Kong harbour, served the poor in the slums of Naples and flown with the Australian flying doctor service. Her first book, Behind the Veil, describing her adventures in Saudi Arabia, has been an Australian best-seller.

Lydia Laube, when she is not travelling, divides her time between Adelaide and Darwin.

The Long Way Home

Nobody goesthatway

Nobody goesthatway

LYDIA LAUBE

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

Australia

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published August 1994

Reprinted December 1994, 2002, 2009.

This edition published 2010

Copyright Lydia Laube, 1994

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover design by Bill Farr

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Laube, Lydia, 1948 .

The long way home.

ISBN 9781862548992

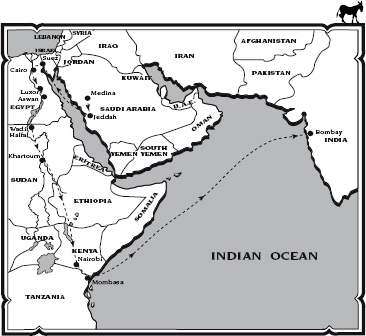

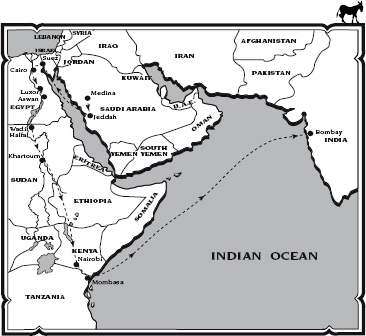

1. Laube, Lydia, 1948 Journeys. 2. Saudi Arabia Description and travel. 3. Egypt Description and travel. 4. Sudan Description and travel. 5. Kenya Description and travel. 6. India Description and travel. I. Title.

915.04

To the memory of my father

Contents

By the same author

Behind the Veil

Bound for Vietnam

Is This the Way to Madagascar?

Llama for Lunch

Slow Boat to Mongolia

Temples and Tuk Tuks

Twenty thousand feet above the Himalayas, entombed in the bowels of a jumbo jet, is no place to change your mind about your destination. Given the chance, though, I would have absconded with the greatest alacrity. Daft I had been to venture into Saudi Arabia when it was an unknown quantity, but stark raving mad I must be to be returning.

When I had left Medina, supposedly on leave, but quite sure it was for good, the company employing me had given me a return ticket to Australia and back. From the complacent safety of Adelaide, it had seemed a waste not to use it. Air tickets to the Middle East are very expensive and I wanted to visit Egypt again. There was also the matter of the large amount of money the company still owed me.

My six weeks at home had flashed by and, before I had really thought about it, the date on my return ticket had arrived. It was time to go. And I did. Time had softened the memory of the deprivation of my exiled life outside the walls of Medina, Islams second holiest city.

Before I departed Adelaide I phoned the company administrator in Saudi Arabia to discover my destination. He said I was to go to Mustafa Khalid bin Rachman, the other hospital they managed at Medina, which had been left suddenly without a nursing director. Horrified, I reminded him of the promised transfer elsewhere than Medina. He replied that it would only be for a little while, that they would transfer me elsewhere as soon as a replacement could be found, and that I could leave at any time if I did not like it. So I agreed.

I looked around the plane. Saudias international aircraft were the latest models and obviously designed to convince the world of Saudi Arabias affluence. At the check-in counter in Singapore I had been upgraded to first class. It seemed to be the practice to do this if there were vacant seats and the few Europeans who fly with Saudia were usually given these in order to impress them. Saudia appears to have an inferiority complex about its dry status the reason most Europeans give it a miss so it tries to make up for this failing by supplying every other possible luxury. They succeeded. I was impressed.

My seat was an enormous lounge chair and my neighbour a genuine, original sheik. He had swept aboard, long white thobe swishing around his soft camel-leather sandals, dark brown camel-hair cloak trimmed with gold braid flowing impressively behind him, and the traditional red and white checked gutera on his head. Finding me there alone was obviously a shock, but he quickly recovered his composure, salaammed and greeted me courteously. His secretary, who was billeted in tourist class with the common herd, and only ventured now and then into our rarefied company, told me that my companion was the Sheik Anwar bin Kalim al Suddah and that he was a great leader of the people of the Western Desert.

Sheik Anwar said, I have been to Singapore to see my younger sons. They are studying at the university.

How many? I asked.

Three, he replied, the others are in London.

I wondered how many others there were, but felt it might be exceeding the limits of courtesy to enquire. I asked him whether he had any horses, knowing that was a safe bet, and we talked about them instead, a subject we both found interesting.

You may come and ride my horses one day, he offered kindly.

En shallah, I replied, God willing.

But we both knew that I could not.

The flight was bumpy for most of the nine hours of its duration and, white knuckle flyer that I am, this made me twitchy, but I consoled myself with the fabulous food, which even included caviar.

On arrival at Riyadh at eight in the evening, I found that I had missed the last flight to Medina despite the excellence of their airline, Saudia still had not been able to eliminate the Arab lack of interest in timetables and I was forced to spend the night in the airport. I wasnt able to leave without someone claiming and acknowledging receipt of me. The male desk staff most courteously suggested that I should avail myself of the Womens Room for the night and directed me to it. I had fears that it might be the same place in which I had been detained on my previous arrival. I did not want any reminders of that unpleasant experience when I had been unceremoniously shunted into a room, also designated Womens Room, and given into the charge of two huge female chaperones covered entirely in black cloth. Convinced I had been arrested, but with no idea why, I had been almost panic stricken, but had practised eastern calm for an interminable time until eventually released into the care of the company representative.

I discovered later that I had caused such consternation because I was alone. A woman cannot be responsible for herself in Saudi Arabia. She has no separate identity, but is always merely the appendage of a male.

My lack of a husband, that essential accessory, had sorely hindered me. At times I had longed for a husband. Anybodys.

This time I had no problems about being alone. I had an ongoing ticket to Medina and my work and residency papers to prove that I was not a loose woman, and before the plane landed I had done as the old hands do, donned my

Next page

Nobody goesthatway

Nobody goesthatway