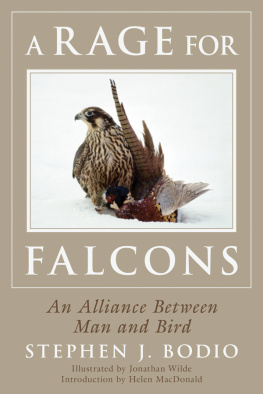

Copyright 2012 by Stephen J. Bodio

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Heather Santiago

Layout: Maggie Peterson

Text design: Maggie Peterson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-8981-8

To the late Aralbai of Bayaan Olgii and the very much alive Lauren McGough of Oklahoma, Mongolia, Scotland, and who knows where next: Berkutchis.

Some decades ago I, with several other people, was involved with a natural history writing program in Vermont, all of us trying to guide makers of mud ball prose in their journey toward clarity and grace. Several of the instructors had rooms in the same building and shared a common kitchen. At the end of the second day, I looked forward to a cold drink on the porch while watching evening bats in the twilight. I reached into the refrigerators grim little ice cube compartment and pulled out a tray. Instead of ice cubes the cavities contained an assortment of moths, large and small. One was a luna moth, a creature I had not seen since I was a child. Had they made their way into the compartment during the weeks the refrigerator stood empty and gaping? But then the kitchen door opened and a tousle-headed man with glowing eyes came in.

My moths! he said to the ice cube tray, as one would say my long-lost twin brother! It was my first meeting with Steve Bodio, whom I knew only from his essays in Grays Sporting Journal. I got used to seeing him crouched by the screen door at night waiting for new moth victims and to listening to monologues about startle patterns, mimicry, and melanism. Before the session was over, I knew this ardent biologist-naturalist a little bettera man who collected insects, raised pigeons, and hunted with falcons and hawks; collected rare books on the natural world; was vastly well read in history, paleontology, archaeology, and climatology; knew about ancient horses, the history and habits of the dog, and Egyptian mummification processes; could quote from Buffon, Charles Wilkes, William Bartram, Wilfred Thesiger, and the authors of little-known treatises on gyrfalcons and eagles; an eager talker on all subjects. Years after I met him he contracted malaria in Zimbabwe and of course developed a fascination with parasite evolution. He was the kind of restlessly curious fellow who might have ended up living with some remote tribe. In fact he continued his examination of the world from a home base in one of the emptier regions of New Mexico in a house full of books, bones, dogs, and raptors and with a shady backyard mellifluous with his extensive pigeon collection. Eventually I lost touch with Bodio, for years depending on news from our mutual friends, Louise and Bob Jones, who always had a first-rate Bodio story.

Bodio learned something of grief when his wife Betsy died. No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief His beautiful memorial book, Querencia (a reference to the safe place in the bull ring where the beleaguered bull takes his stand), was only briefly available before his amateur then-publisher decided bookstores were part of a corrupt system and locked the copies away. Only through the help of Montana writer friends and lawyers was he able to regain the copies and copyright. For several years after Betsys death he stumbled around with various women until he met the extraordinary Elizabeth Adam (Libby)archaeologist, Outward Bound guide, chef and caterer, mountain climber, world traveler, musician.

Bodios passionate enthusiasm for animals and birds and his low interest in careerism have led him occasionally into shoal waters, and he has eked out a fingernail kind of living. He is a natural history writer with an unquenchable desire to learn about the creatures that share the planet with humans. Following his interests has come at the cost of a decent income, partly because he is interested in such nonmainstream subjects as animal behavior and hunting, cockfights, falconry, and other blood sports in a time when people are increasingly estranged from the natural world and the harsh lives of nonhuman creatures in it; if it isnt domesticated, it doesnt count. As Bodio somewhat bitterly puts it, I am, at least in todays journalistic niche ecosystem, classifiable as a travel writer and a nature writer. His interests have taken him all over the world, in particular to Central Asia to be in the company of high-altitude falconers and eaglers.

Most birders are concerned primarily with making lists of the number of birds they have identified, a rather artificial category of knowledge that tells us little about ecosystems and specific habitats. I was surprised last year reading Jonathan Franzens The Discomfort Zone. All Franzens heart-wound writing urges one to reexamine oneself in the matrix of family and impinging crises. I was attracted to the section on his bird-watching period (My Bird Problem), enlivened with brilliant descriptions of several birds and his identification with birds, his journey from clumsy curiosity to headlong obsession. The birds metamorphosed into piteous, poor creatures; then somehow they became Franzen himself then became his mother, who was dying of colon cancer. In the end Franzen revealed himself as a species-list striver going for four hundred, and when he achieved that goal he became weary of birds and birding.

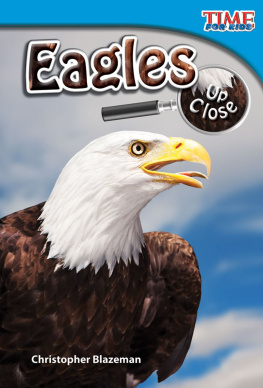

Those of us who are interested in bird behavior beyond the feeder or the identification guidebook find meager pickings when it comes to information. I am fortunate that my house faces a cliff with a river at the base where I can watch raptors, waterfowl, and a hundred other species. The nests of a pair of bald eagles and another upriver inhabited by golden eagles are in sight from the breakfast table. I have plenty of books on birds, but the information on why the big eagles do what they do is hard to dig out. Eagle behavior is usually lumped together with the general behavior of the accipiters, but a single book that focused on the rich lore and sweep of eagledom did not seem to exist. For years I have relied on observation, folklore, and the eagle stories of a few rural neighbors and friends who take notice of them. Bodios beautifully written and authoritative book Eagles is a primary source of information as well as an omnium gatherum from literature, film, and mythology concerning these large, striking birds.

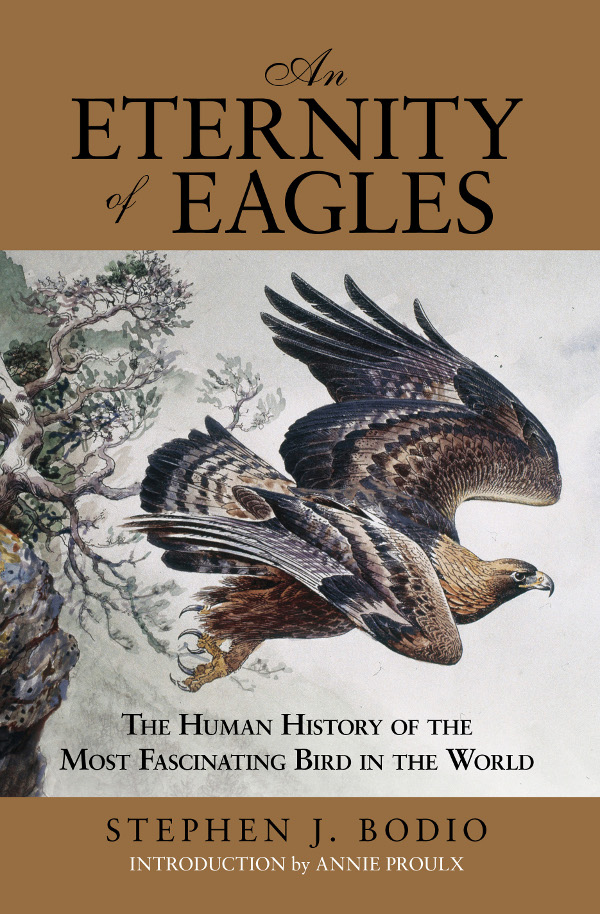

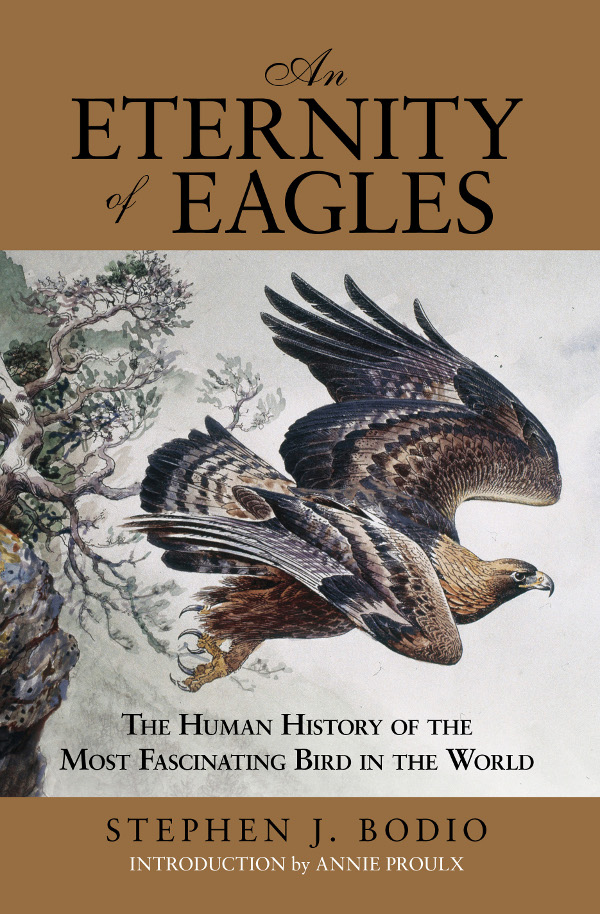

Birders are often puzzled by avian plumage that is not constant but changes with age, season, and locality. Keeping track of such variables for many species, plus pre-molt and molt stages, is terrifically complex. In an effort to simplify the birders eternal question, What bird is that? the reductionist approach of bird identification guidebooks gives the impression of immutable species in a fixed world. Bodio, in his discussion of ever-branching cladistic analyses of changing species in transitional habitats, reminds us that species classifications are human constructs and that mutability is the common denominator of life. Once we grasp an idea of the fluid currents of changing habitats and climates and the creatures that fit themselves to those changes, we can look for adaptive and opportunistic behavior as well as size and feather color. This sense of modification underpins Bodios book as he introduces us to the current eagle groups: the sea eagles, which include the familiar bald eagle; the snake eagles; jungle eagles; odd eagles; and booted eagles, considered the true eagles by most of us. The booted golden eagle, says Bodio, is the quintessential capital-E eagle, the Platonic ideal of a bird of prey Bodio also introduces us to unfamiliar eagles as the huge flying wing bateleurs of the sub-Sahara, the Indian black eagle with paddle shaped wings and exceedingly long tail, and the tiny little eagle of Australia.