This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2017

by The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

N EW Y ORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact ,

or write us at the above address.

Copyright 2003, 2017 Tony Hall

This edition was revised and updated by C. Stephen Heying

First published in the UK in 2003 by Swan Hill Press,

an imprint of Quiller Publishing Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-4683-1453-3

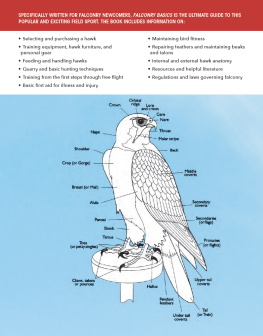

With 75 b&w drawings and 5 photographs

The ancient practice of falconry first gained traction in the United States in the twentieth century, and the U.S. now boasts an ever-growing community of falconers as worldwide demand for American-bred birds of prey increases. In this fully revised edition of his classic guide to falconry, lifelong falconer Tony Hall presents the most comprehensive information available to newcomers to the sport. Updated by American falconer C. Stephen Heying, Falconry Basics is specifically designed for novices and covers the basics, from different types of birds and their individual characteristics, to acquiring the proper equipment and the care and handling of the birds themselves.

Covering all aspects of training, hunting, and maintenance, Falconry Basics addresses every possible scenario a newcomer may face when training their first raptor, from illness and injury to escaped or overconfident hawks. Hall also provides a wealth of supplementary information for beginners, including notes on anatomy, terminology, and a list of additional resources. Heyings updates to this revised edition include the current legal requirements for owning and hunting with a raptor in the United States, the types of hawks native to various regions of North America and the quarry encountered there, and resources for falconry apprenticeship. Accompanied by diagrams and detailed line illustrations throughout, this book will become a standard manual for future generations of falconers.

Common (or European) buzzard (Buteo buteo)

T HROUGHOUT THIS BOOK THE TERM HAWK IS USED FOR ALL FALCONRY BIRDS . T HIS usage complies with falconry tradition, but not with dictionary-making, which restricts the word to a group of birds known as accipiters (such as Sparrowhawks and Goshawks). Similarly, the term falconry means the training and flying of all kinds, not just falcons such as the Peregrine.

In the sports very long history many names have been used to distinguish one kind of falconer from another. For example, austringer for a person who trained and flew Goshawks; sparviter for one who flew Sparrowhawks; hawker for one who flew any kind of accipiter; and falconer for one who specialized in flying falcons (meaning the female Peregrine). These days, even falconers dont often use such distinctions, partly because most own and fly several different kinds of hawk, and partly because no-one outside the sport would have the faintest idea what an austringer or a sparviter was and wouldnt be enlightened by consulting any standard dictionary.

Another long-standing protocol is that all falconry birdswhatever their sexare referred to as she or her when speaking in general terms. Female hawks are usually larger and more powerful than males. Centuries ago this probably made them more desirable, and therefore more prominent. But falconers learned long ago that males and females are just different, and each sex has its own special attributes. But the protocol is well established, and in this book I have respected it. Similarly, when I write hemeaning the falconer or his dogno sexism is intended. It simply makes things clearer, especially when she is the hawk.

On a more general level, all known forms of life have a scientific as well as a common name. Each scientific name is unique and recognized worldwide. Scientific names are given firstly to describe each organisms relationship (taxonomy) with other life forms, and secondly to avoid confusion. For example, taxonomically, all falcons have something in common with each other, as do all hawks and all buzzards. Also, Britain, North America, and Australasia all have hovering falcons called Kestrels, but each bird is a different species. Having a scientific name for each makes it clear which one is being talked about.

There are several levels of taxonomic classification (Orders, Sub-orders, Families, and so on) but the two lowest levels, the genus and specieswhich provide the most precise descriptionare the ones we are interested in. The generic and specific names are usually all that is necessary to identify each life form uniquely, and it is customary to begin with a capital letter and to write the name in italics, as in Homo sapiens (human beings). The specific name often refers to some characteristic of the species sapiens, for example, means wiseand occasionally a second specific name is added to identify a recognizable sub-species or race. One of the many examples of this in the bird world is Falco peregrinus anatum, a race of Peregrine falcons originating in Canada and North America. Another useful convention when quoting a sub-species is to write only the initial letters of the nominate species, provided it is clear which you are referring tofor example: F.p. anatum.

Scientific terminology has also been used, where appropriate, throughout this book.

I ACQUIRED MY FIRST BIRD OF PREY IN 1958 WHEN I WAS FOURTEEN YEARS OLD . S HE WAS a young Tawny Owl, and I blundered across her at the foot of a tree. She was only half-fledged, and had somehow tumbled out of her nest. Knowing no better, I picked her up and took her home.

After a bitter battle with my parents (who were fed up with me bringing wild animals into the house), I kept her in my bedroom and sustained her with rats, mice or voles which our two cats brought in. If supplies from this quarter failed, I went out and caught my own. If I failed too, I thieved scraps of meat from the larder. One way or another, I kept her alive until she was fully-fledged. Then I took her out into a field bordering the woods where Id found her, threw her up into the air, and let her fly. Released from my grasp, she glided gracefully into the woods and I saw her for the very last time.

I sincerely believed Id saved her life. I know now that I probably condemned her to a slow death through starvation, and this probability has haunted me for many years. Although I didnt know any better at the time, that doesnt provide much comfort and I doubt that I will ever really forgive myself.

At the foot of a tree she was vulnerable, but her parents were probably nearby and still actively feeding her. Exposed as she was, close cover was all around and she was perfectly capable of reaching it. Had she done so, it would have provided some protection from foxes and other predators (including me). Once fully-fledged and able to fly, her parents were programmed to teach her how and what to hunt, and perhaps even assist in this process until she developed the skills and experience to do it alone. My intervention, however well meaning, had deprived her of this vital life-saving education.