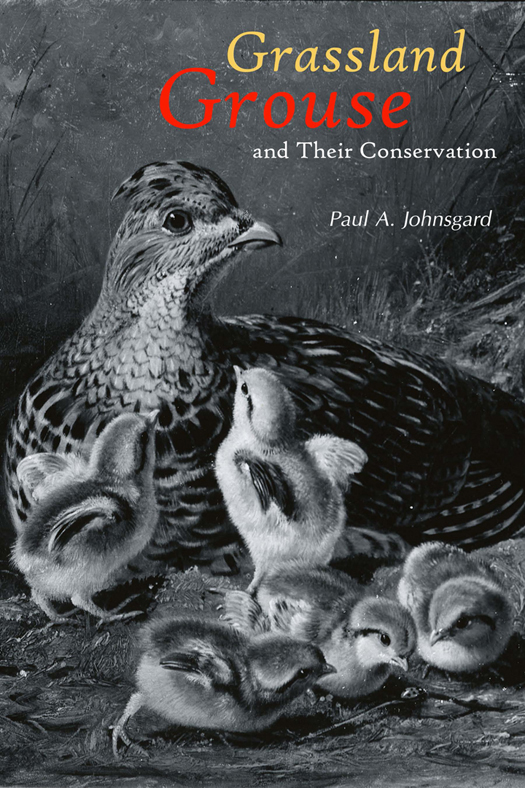

Frontispiece. Ruffed Grouse by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait. Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Detail reproduced on front cover.

2002 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Copy editor: Anne R. Gibbons

Production editor: Duke Johns

Designer: Janice Wheeler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnsgard, Paul A.

Grassland grouse and their conservation / Paul A. Johnsgard.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.).

ISBN 1-58834-039-2 (alk. paper)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-935623-67-0

1. GrouseNorth America. 2. Birds, Protection ofNorth America. I. Title.

QL696.G285 J629 2002 2002021012

598.63097dc21

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the author. The Smithsonian Institution Press does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually, or maintain a file of addresses for illustrations sources.

v3.1

Dedicated to the prairie grouse pioneers: Alfred Gross,

Aldo Leopold, Ingemar Hjorth, Frederick and

Frances Hamerstrom, and, of course, all the Gaboons

CONTENTS

PREFACE

After I published The Grouse of the World in 1983, I thought I would never again revisit the grouse family as a subject for a book. Indeed, my attention soon turned to other avian groups, such as hummingbirds, owls, hawks, and trogons, all of which seemed to me to warrant more scrutiny and immediate conservation concern than the grouse. In my preoccupation with these subjects over the past 20 years I failed to see that a disturbing trend was developing with regard to the North American grouse, namely that their populations were almost universally declining, especially in the case of the grassland-adapted species. There are also three species of tundra-adapted ptarmigans (Lagopus spp.) in North America and three species of forest-adapted grouse, namely the blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus), spruce grouse (D. canadensis), and ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus), but none of these has suffered the degree of population and range declines that have occurred in the prairie grouse.

I first began to perceive this disturbing trend during my preparation of Prairie Birds: Fragile Splendor in the Great Plains, which was written in large measure to try to document recent habitat and population changes in some 30 species of birds that are especially associated with Great Plains grasslands. These species include the greater and lesser prairie-chickens and the sharp-tailed grouse. I gradually became aware of the increasingly critical status of the Attwaters prairie-chicken, a Gulf Coast race of the greater prairie-chicken that seems likely to follow the ill-fated prairie-chicken of the East Coast, the heath hen, into oblivion before many more years have passed.

In subsequently reviewing population data on prairie grouse populations throughout the Great Plains, I was shocked to discover they had declined sharply since my earliest attempt to summarize their national status (Grouse and Quails of North America) and both the greater and lesser prairie-chickens had essentially or entirely disappeared from several states during the past 30 years. These losses occurred in spite of the fact that the Endangered Species Act was passed in the early 1970s, which led ornithologists and other biologists to believe we had finally been given a cushion of protection from such catastrophic events as a species total elimination, at least when measures could be taken to prevent it.

An explanatory note: the heath hen, the Attwaters prairie-chicken, and the greater prairie-chicken occurring in the continental interior are now all simply regarded as geographic races of one rather variable species, the greater prairie-chicken. Although current ornithological practice frowns on giving distinctive names to populations that are only geographic races, I have often had to make it clear whether I was referring to the greater prairie-chicken species collectively or only to one of these three races. Using heath hen for the eastern race (Tympanuchus c. cupido) and Attwaters prairie-chicken for the Texas coastal race (T. c. attwateri) provided an easy and well-accepted solution for those two forms, but a convenient English title for the race that historically occurred throughout the continental interior (T. c. pinnatus) remained problematic. Various authors have designated this form as the prairie hen, the western prairie-chicken, or the northern prairie-chicken. I have settled on referring to it as the interior greater prairie-chicken to distinguish it from the other currently accepted races of the greater prairie-chicken whenever it has seemed necessary.

I have also followed long-held tradition, but not current American Ornithologists Union (AOU) practice, in using English names for distinguishing the three races of sharp-tailed grouse discussed in this book, namely Columbian sharp-tail for T. phasianellus columbianus, plains sharp-tail for T. p. jamesi, and prairie-sharp-tail for T. p. campestris. Finally, the appearance of a newly recognized sage-grouse species, the Gunnison sage-grouse (Centrocercus minimus), has meant that the original sage-grouse (C. urophasianus) needs a comparable modifying English name. I have referred to it as the greater sage-grouse, the name recently adopted by the AOU, with its subsidiary races referred to as the northern (C. u. urophasianus) and western (C. u. phaios) greater sage-grouse.

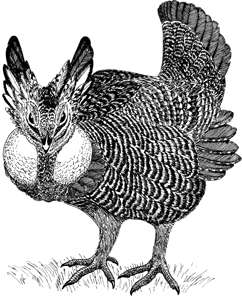

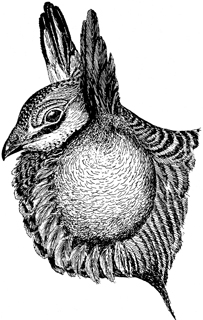

Because essentially all the technical literature on grouse ecology and biology has been based on traditional English unit measures (miles, acres, etc.), I have used these units except for a few cases where the original measurements were given as metrics, in which case I have provided both. I have given direct (parenthetical) literature citations in captions for maps and figures, but not in the text. Where I have felt that specific statements as to sources are needed in the text, the authors or primary authors name is provided, to allow readers to locate the citation in the bibliography. Where no such source is mentioned I considered the information to be available in standard references, such as my two earlier books on the grouse (Grouse and Quails of North America; The Grouse of the World) or in The Birds of North America monographs on each of the prairie grouse species (Connelly et al.; Giesen; Schroeder and Robb; and Schroeder et al.). The drawings and maps are all my own, with documentary sources indicated as necessary.