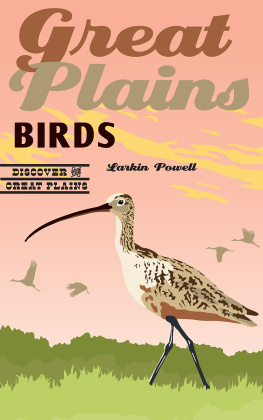

G RASS,

S KY,

S ONG

Promise and Peril in the World of Grassland Birds

T REVOR

H ERRIOT

For Karen

C ONTENTS

Preface

A W AY H OME

How do you know but that evry bird that cuts the airy way Is an immense world of delight closd by your senses five?

W ILLIAM B LAKE

O n warm, clear nights near the end of April, a barely noticeable movement begins in the skies over the grasslands of Montana, North Dakota, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba. For three weeks or more, snow geese have passed by in the milky light of the moon, yelping excitedly of arctic pastures ahead of them, but now there are softer notes falling from the night air, voices easily lost in the clamour of a prairie spring. These are the contact calls of Spragues pipits and chestnut-collared longspurs returning to the northern Great Plains, where they will spend the summer. As day breaks, they will look at the land below and compare its patterns of colour, light, and shadow with patterns they carry in their genes or in their memories. If they see the monotone of cropland or the longer shadows of bush and shrubs, they will fly on.

Within a day or two the pipits will choose an upland site with longer, thicker grass and some thatch left over from the year before, while the longspurs will settle for shorter, grazed-down pastures. They will join the horned larks and western meadowlarks already on their nesting grounds. The males will sing over their piece of prairie; the females will accept or reject them. Bonds will be made, nests will be stitched out of grass, eggs will be laid. The summer-long winnowing down through the perils of weather and predators will begin. Some eggs will survive to hatch, some nestlings will survive to fledge, and some fledglings will survive to disperse and migrate south in fall.

Biologists place these birds in a group they call grassland obligate, meaning that they are among the species that depend on grassy habitats. In North America, the term is often applied to the pipits, prairie hawks, longspurs, and other birds that breed only on the high plains of the west, but in its broadest sense it includes the bobolinks and field sparrows found in small hay meadows from Ontario to Florida, the wrens and sparrows that use wetter grasslands, and the shorebirds, hawks, and owls that nest in grassy places from coast to coast. As a group, birds that need grass are declining faster than any others on the continentmore than birds that nest in forest, wetlands, mountains, urban areas, tundra, or desert. Some of these species will vanish from large portions of their breeding ranges in the next twenty to thirty years; many already have.

In the triage that determines which environmental issues receive attention, something like the decline of grassland birds barely makes the waiting room. Amidst the din of the ecological emergencies that gain public attention by threatening discomfort and extinction changing climate, collapsing fisheries, looming pandemics, vanishing aquifersan alarm set off by a few small brown birds in the middle of nowhere has little chance of being heard. People try to make economic arguments for the protection of grassland birds, but the argument always bears the strained tone of a lawyer defending a client he knows to be doomed. The damnable truth is that if ten or fifteen species went extinct tomorrow we would have trouble detecting any significant ecological or economic consequences. The water and nitrogen cycles would carry on in their absence. The soil would continue to grow crops. The ecology of grassland places might shift, but few of us would be able to discern any change. Farm production and its attendant economies on the Great Plains would make a slight adjustment to account for the loss of some natural weed and insect control and then get back to business as usual. Tourism publications and marketing plans might need some revising, but any shortfall in tourists would be minor and easily managed with new campaigns. A few birdwatchers, some rural people, and environmentalists would kick up a fuss, but the majority of people would not notice or care.

Its a fools dream, but a part of me cant stop imagining that if enough people would discover all that is good and holy in these birds, we might be able to turn things around before its too late. Every spring the wish comes back even if the birds do not. I drive out to a local pasture in early May, open the car door and listen. I try to enjoy the air, the light, and the birdsong, but Im holding my breath. A sense of dread creeps in as I realize that the song is not what it was last year: one longspur is singing where there once were six. No upland sandpipers, no Bairds sparrows. Burrowing owls gone for a decade. The exaltation of a prairie spring reduced to a few meadowlarks and savannah sparrows holding their own. I drive back to the city wishing things were different, wishing I didnt know how the pasture used to sound, and wishing I could get others to see the spirit made flesh in such birds.

For a naturalist, this is a dangerous kind of desire. It begs for more than pure natural history can provide, and then takes its questions to the narrow and treacherous terrain that runs between faith and reason. You stumble back and forth between the testable statements of science and the untestable impressions of experience, looking for ways to locate in words something of the lyric and resonance of living mysteries. Both sides tempt the mind with a lofty roost from which it can pronounce philosophies, reasons, and solutions, as though we might think our way to the grace of living in a just relationship with the other-than-human world. Prairie people, I believe, are more susceptible than most. The simple act of standing upright on the high plains is enough to foster delusions of dominion and knowledge.

Navigating that terrain between the knowable and the unknowable, this book follows obscure and diminishing birds into the shadow of a wounded land. Each story, argument, species profile, and drawing was conceived within a longing to reclaim the original spirit of grassland that survives yet in its birds. Beneath that longing lie the deeper human wish we all share: to find out how we might belong to a place, to find a way home. Precise directions are hard to come by, but for those of us who live on the Great Plains I have an idea of where we might at least take our bearings. Its that place at the edge of town where a large patch of wild grass grows, the little field that no one mows. Try going there sometime. Walk into the middle and lie down. Press your back against the earth and let the exhalations of the soil enter your body breath by breath. With grass blades waving overhead and the sky beyond, the human spirit has half a chance to come to its senses. If there are birds singing in the air, all the better. They will tell you where you are and, if you listen long enough, they may tell you who you are in the bargain.

Growing up in prairie towns and cities, I never once considered the grassy places beyond the ball diamond or the unploughed land at the edges of my grandfathers fields to be anything but ordinary. If there were birds in the grass, no one paid any attention to them. The exception was the sharp-tailed grouse. Chickens my father called them as we walked the field edges on fall afternoons, killing time and a few grouse between morning and evening duck shoots. The long walks in rubber boots seemed like some kind of penitential trial by boredom, so I would daydream most of the way in the drowsy warmth of my parka, my feet finding places between the clods of summerfallow or stubble. Small birds would sometimes fly up from swaths of grain, but their chittering cries were nothing more than the ambience of an October chicken hunt, the sounds that accompanied a plodding reverie.