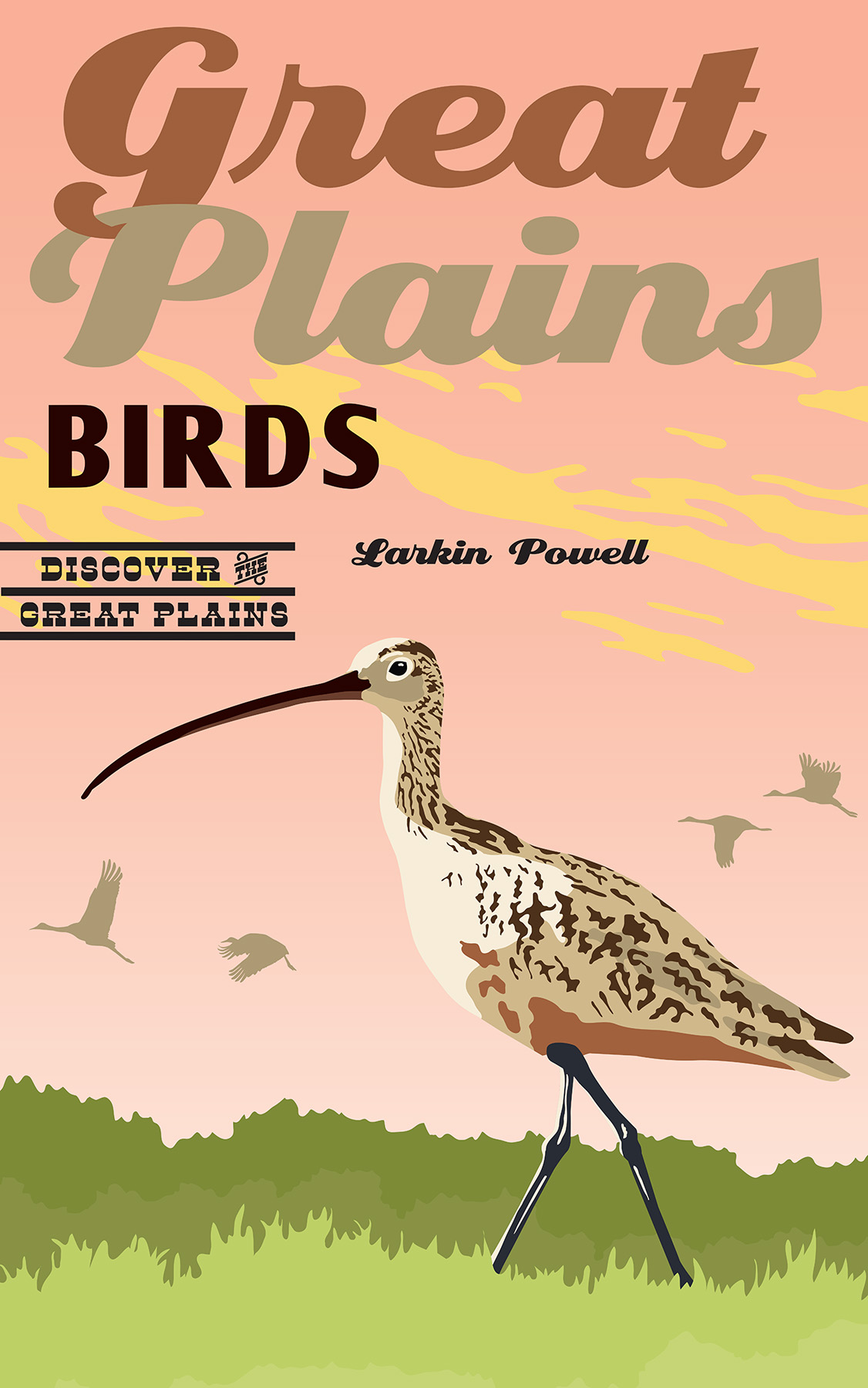

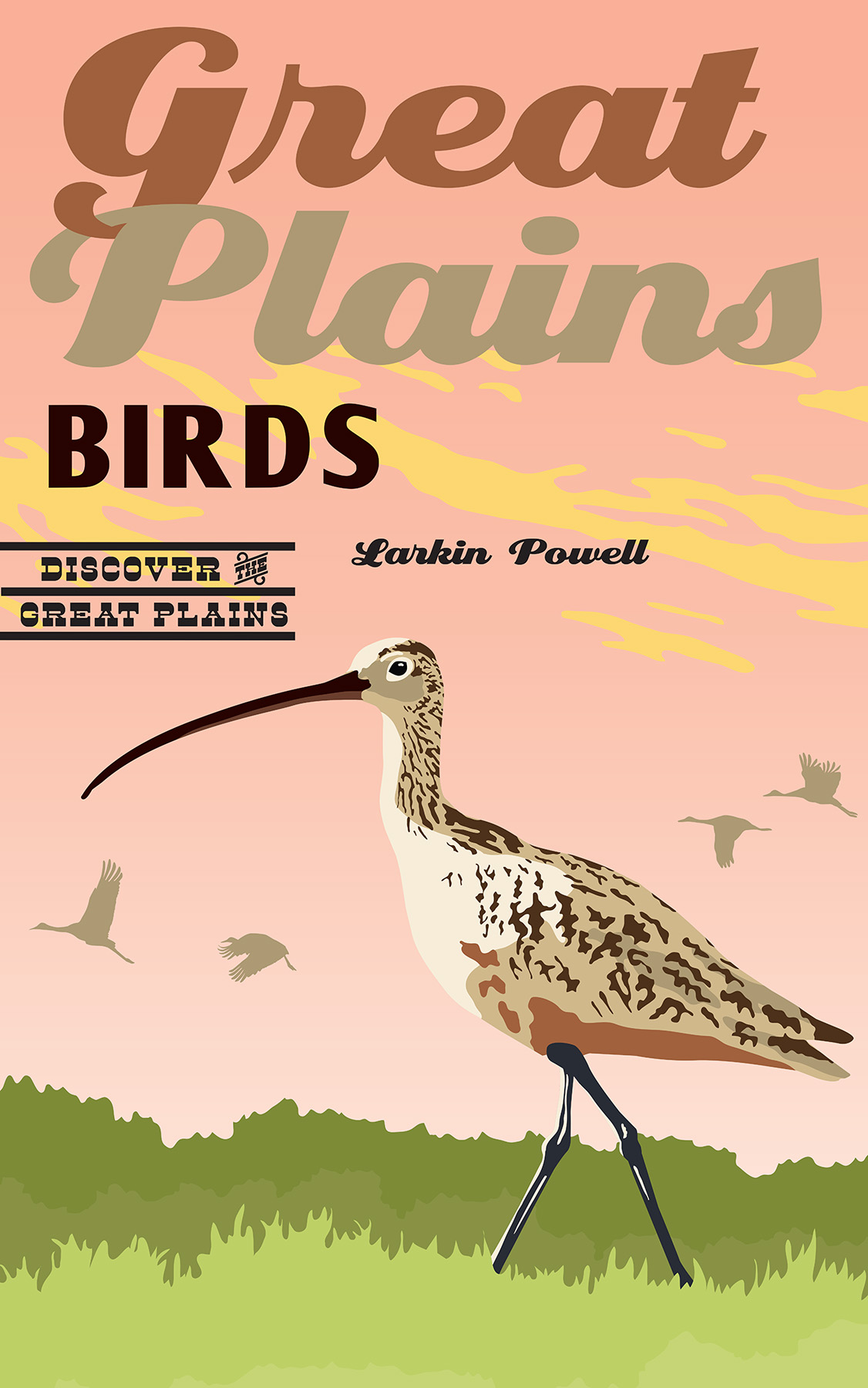

Powells personal love for the Great Plains and its birds is contagious. This book plays a critically important role in raising awareness, building appreciation, and calling for conservation action for North Americas most threatened birds.

Martha Kauffman, managing director of the World Wildlife Fund, Northern Great Plains Programs

With this book, you are accompanied by your personal storytelling guide while discovering this underappreciated region of North America. Wisdom on geology, natural history emphasizing birds, wildlife management, and history is offered in an engaging narrative.

Gary C. White, professor emeritus of fish, wildlife, and conservation biology at Colorado State University

This book entices and prepares readers to make their own personal connection to the heart of North America through its most inspiring occupants, Great Plains birds.

Sarah Sortum, rancher and ecotourism provider

From modern day prairie birds (and where to see them), to geography, history, and conservation, this book is an excellent introduction for anyone wanting to learn more about the vast heart of America, the Great Plains. Wonders abound, if only we look.

Joel Sartore, Photo Ark founder and National Geographic photographer and fellow

My high expectations were met when I read Larkins book Great Plains Birds, but they were exceeded when I found myself laughing and living vicariously through his personal narrative. This book is honest and important and presents a clear-eyed view of bird conservation today in our heartland.

Michael Forsberg, photographer and author of Great Plains: Americas Lingering Wild

Discover the Great Plains

Series Editor: Richard Edwards, Center for Great Plains Studies

Great Plains Birds

Larkin Powell

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

A Project of the Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska

2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image courtesy Katie Nieland.

CCL following photographers names in captions indicates use as allowed under Creative Commons license; all photos used with permission.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Powell, Larkin A., author.

Title: Great Plains birds / Larkin Powell.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2019] | Series: Discover the Great Plains | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006780

ISBN 9781496204189 (paperback: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496218599 (epub)

ISBN 9781496218605 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496218612 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : BirdsGreat Plains. | BirdsGreat PlainsPictorial works.

Classification: LCC QL 683. G 68 P 69 2019 | DDC 598.09764/8dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006780

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To my teachers: Lyle Babberl, Charles Eilers, and Nicholas Hartwig, who inspired my passion for nature, and John Judd, James Lippold, Lana Hicks, and Jon Wallace, who showed me how to tell stories

, from W. E. Webb, Buffalo Land (1872).

All rivers and creeks were alive with beaver, otter, mink, muskrats and raccoons, along with various kinds of geese, ducks, pelicans, swans, and other water birds. These birds of passage appeared by the thousands every spring and fall. Cranes, gray and white, and several species of wood cocks were seen in large flocks. All this had changed entirely in the fifty years that have passed since the founding of our settlement. The above-mentioned birds and animals whose great multitudes gave the land its peculiar character and appeal in those early days have decreased in numbers to almost the vanishing point.

William Stolley, 1907

Contents

I am grateful to anyone who has shared time in the woods, wetlands, or grasslands during birding and research adventures with me, because shared moments are sacred moments. Eventually stories seem to come from sacred moments.

Richard C. (Rick) Edwards challenged me with this project and Katie Nieland provided assistance to shape the narrative. Two anonymous reviewers made constructive comments. The book would be much less colorful without the wonderful photos provided by a set of photographers who are adept at their craft. Each image is a result of patient hours in the field. Parts of this book were written at Namib Rand Nature Reserve in Namibia and at the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust in England. My son, Tristan, deserves gratitude and some meaningful father-son time for letting me disappear into the writing room for hours on end. Thanks to my wife, Kelly Powell, for telling me to rewrite the first draft in my own voice. It is possible that she was correct.

It has been my pleasure to seek the truth about birds and how they use our landscapes with a set of generous colleagues over the years: my graduate advisers William Clark, Erwin Klaas, David Krementz, and Michael Conroy; field research collaborators Mark Vrtiska and Walter Schacht; ecologists George Gale, Andrew Tyre, John Carroll, Kevin Pope, T.J. Fontaine, David Wedin, and Mark Pegg; and seven handfuls of undergraduate researchers, graduate students, and postdocs. All have provided insights and support that have inspired information provided in this volume. Finally, my research career would not have been the same had it not been for my mentor and colleague, Mary Bomberger Brown, who has modeled a life driven by service to feathered and unfeathered friends everywhere.

Sources of the Native American legend stories:

Prairie-chicken Dance Origin told by Garan Coons, Sioux dancer, at Burwell, Nebraska, 2012. Recorded by Larkin Powell.

Why the Crow Is Black told by Good White Buffalo at Winner, Rosebud Indian Reservation, South Dakota, 1964. Recorded and transcribed by Richard Erdoes in Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz, American Indian Myths and Legends (New York: Pantheon, 1984).

Why the Curlews Bill Is Long and Crooked is a Blackfoot legend, recorded and transcribed in Frank B. Linderman, Indian Why Stories: Sparks from War Eagles Lodge-Fire (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

I came face-to-face with migrating birds in the Great Plains for the first time in 1987. It was late March of my first year of college at a small school in southern Iowa and time for spring break. My friends had been planning trips to Colorado for skiing or to the Texas coast for beach lounging. I was an Iowa farm boy, and either option sounded exciting. However, upon breaking the news to my parents, I was informed that I was mistaken as to my spring break activities. Rather, I was, somewhat forcibly, invited to travel to Kearney, Nebraska, with my father to witness the migration of the sandhill cranes.

I should pause here to note that I grew up watching birds with my mother at our feeders, and my father and brother and I enjoyed going on pheasant hunts from time to time. The farm of my youth was a haven for birds, because my parents designed it with grassed terraces and waterways, ponds, and alternate strips of corn and soybeans to be soil and water friendly. However, my basic ornithological background did little to convince me of the benefits of spending a week of my life apart from my friends and, instead, in the company of four hundred thousand large, gangly birds. The clippingwith a large, color photo of these cranes from the travel section of the Sunday

Next page