Contents

Page List

Guide

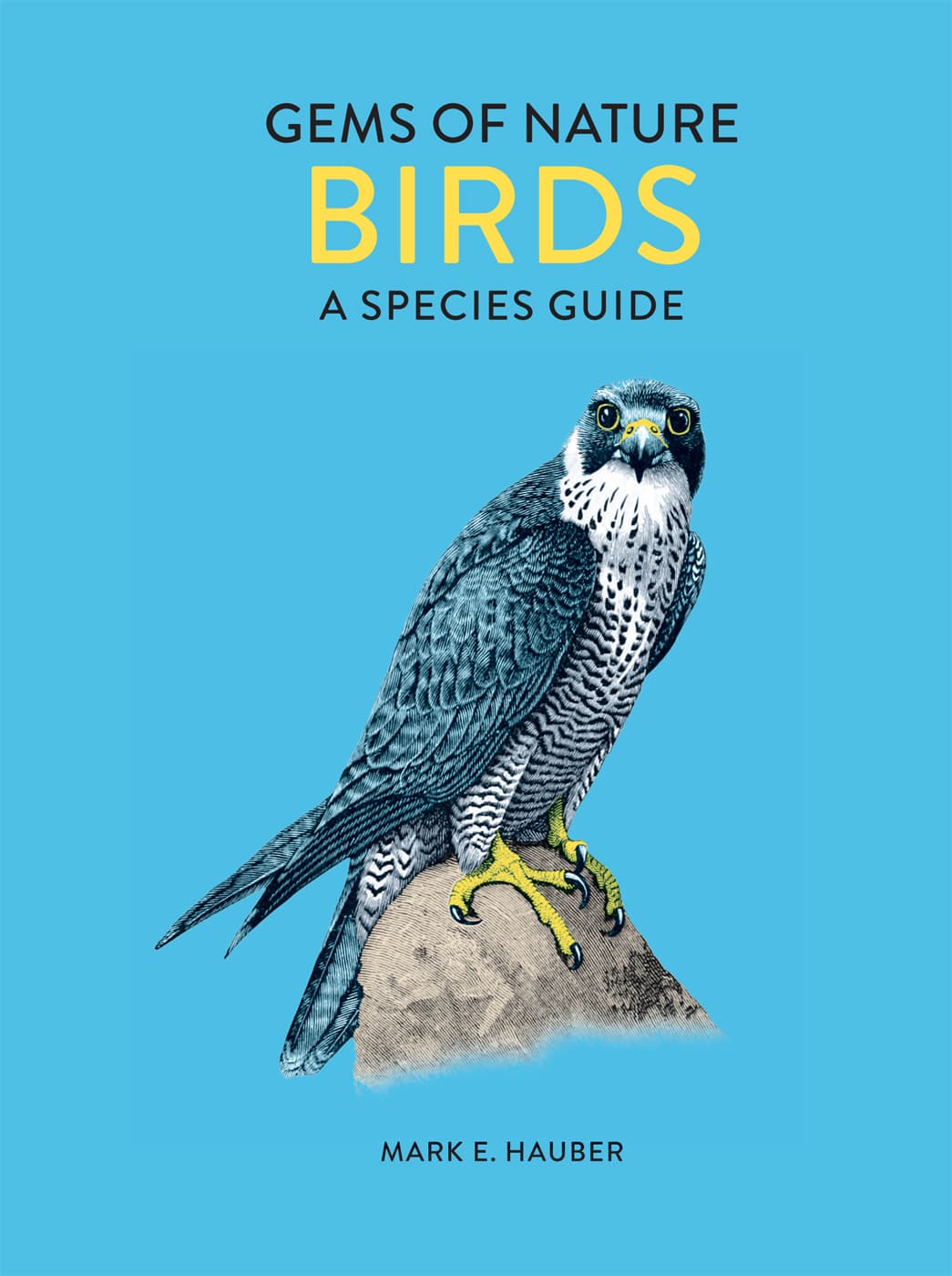

Cover

GEMS OF NATURE

BIRDS

A SPECIES GUIDE

MARK E. HAUBER

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Birds are some of the most colourful and melodious occupants of nature and, with more than 10,000 species on our planet, the amazing diversity of avian life around us easily captures the human imagination. Perhaps because people, much like birds, communicate with mostly sight and sound, we often feel a special connection with the avian companions in our lives, whether it is a pet parrot at home, or an overwintering robin in the local park. Specifically, watching bright and colorful birds at home and away both calms and alerts our senses; and bird songs can remind us of the promise of harmony and peace in the world surrounding us. This book brings you a visual taste of the diversity that exists across the avian world.

Birds and humans also share many other aspects of their daily lives: none closer perhaps than our similarities in family concepts. Most species provide biparental care for the young: even if the males and females and differ in their roles and relative contributions, the majority of birds, like modern humans, live in nuclear families of a mother, a father, and their young. The exceptions to this rule are also fascinating: birds can form vast colonies of city-like nesting habitats, several overlapping generations can cooperate in raising the next brood of new progeny, and single-parent families, led by either a solitary mother or father, are also present in several avian lineages.

Finally, this unique group of modern-day dinosaurs also provides the human imagination with goals that we can hardly achieve: as one of the handful of animal lineages that have independently evolved the ability of flight, fluttering warblers and sparrows within the foliage of a tree and flocks of flying geese and cranes remind us of what we are missing in our daily experiences by living a mostly two-dimensional, pedestrian life. In turn, birds offer scientists much to study because avian species can accomplish feats that few other animal lineages can: they can fly over the oxygen-poor atmosphere of the highest peaks of the Himalayas on their way to and from the wintering and breeding grounds, or dive hundreds of meters deep into the total darkness of the ocean in search of elusive prey. Some birds even converged with bats not only in their abilities to sniff out nocturnal food sources but also to echolocate in deep caves with low light levels.

Let the birds highlighted in this volume take flight with you and your aspirations.

THE EVOLUTION OF BIRDS

Scientists now accept that birds are a specialized subgroup of one branch of dinosaurs, the therapods. While dinosaurs flourished into many different niches of life throughout the Cretaceous, some therapods evolved features allowing them to fly. Archaeopteryx, dating to about 150 million years ago, combined reptile features (teeth, clawed fingers, and a long tail) with wings and flight feathers resembling those of extant (living) birds. While this well-known fossil is no longer considered to be a direct ancestor of modern birds, many other bird fossils show that the earliest forms were small, perhaps arboreal, and able to glide. Modern birds likely evolved their diverse flight behaviors from this origin.

By 100 million years ago, the two major groups of modern birds had split from each other. Based on differences in their skulls, the Paleognathes (old jawed birds) include the flightless ostriches, rheas, cassowaries, emus, kiwis, and the extinct elephantbirds and moas, as well as the flighted tinamous; the Neognathes (new jaws) include the rest of the birds we know today. By the end of the Eocene, about 34 million years ago, all of the modern bird orders (and many of the extant families) roamed and flew in the diverse habitat of our ever-changing planet as members of distinct and recognizable lineages.

Which came first: the chicken or the egg?

This age-old question is an easy one to answer: the egg. Why? An egg is simply a reproductive cell, and animals (including the dinosaurs, the direct ancestors of modern birds) were laying eggs, including the hard-shelled, calcareous eggs of crocodilians and modern birds, for millions of years before the first fowl-like bird evolved. Of course, few non-avian eggs (then or now) looked like modern birds eggs: with a soft membrane and no hard casing in some cases, they can be transparent, gelatinous, and quick to dry out. Most must remain in or near water in order for the young to develop and hatch.

Birds eggs are amniotic, meaning they contain features, including a hard shell and porous membranes, that allow them to be laid and develop on dry land. In the evolution of biodiversity on Earth, the appearance of the amniotic egg made possible a major habitat shift: animals could leave water in order to reproduce. This trait helped amniotesreptiles, dinosaurs, birds, and mammalsto become a dominant form of animal life on Earth.

Packaging life

Why is it that all birds, large and small, put their entire future (embryo, hormones, antibiotics, vitamins, and lipids) into a fragile egg-package?

Humans and the majority of other mammals retain their fertilized eggs inside their bodies, where the developing young receive the nourishment and protection they need to grow directly from the mother. In contrast, a female bird packages everything that is needed to form a chick into her eggand then ejects the egg from her body. Outside, the parent or parents must provide the warmth, shelter, and protection, typically in a nest, that the eggs need so that the embryos can fully develop and hatch into viable chicks.

Amongst the stories included in this book, many highlight the vast array of strategies and choices birds make to find appropriate mates and nesting sites, to warm and protect the eggs, and to assure adequate food, water, and shelter for the chicks. In particular, while the egg itself provides much that the embryo needs, the parents must still provide critical services. Typically, one or both parents provide the external heat necessary to jumpstart embryonic metabolism, and maintain the necessary microclimate, including high levels of humidity, to keep the eggs from desiccating. They select nest sites and build or usurp nests for the eggs to shield them from predators, sun, dryness, and other threats. They also rotate the eggs in the nest to assure even heating or cooling, and to prevent embryonic malformation.