About the Author

Dr Mark Avery is a scientist and naturalist who writes about and comments on environmental issues. He worked for the RSPB for 25 years and was the RSPBs Conservation Director for nearly 13 years. His most recent books include Fighting for Birds: 25 Years in Nature Conservation (2012), A Message from Martha: The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and Its Relevance Today (2014), Behind the Binoculars: Interviews with Acclaimed Birdwatchers (with Keith Betton; 2015) and Inglorious: Conflict in the Uplands (2015). He also contributes to numerous journals and magazines.

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

Remarkable Plants That Shape Our World

The Great Naturalists

The Illustrated Natural History of Selborne

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

IVORY-BILLED

WOODPECKER SPOON-BILLED

SANDPIPER

The Wild Turkey, from which the edible turkey was domesticated, is a surprisingly striking bird.

The sound of the Cuckoo in northern climes heralds the return of spring.

We share the Earth with more than 10,000 species of birds. They soar over the highest peaks and skim over the ocean waves. Their songs fill the rainforests and yet we also wake to their melodies in the middle of our biggest cities. Almost every human who has ever lived has probably seen or heard a bird almost every day. The presence of birds has been a comfort to travellers, a tonic for the ill and a delight to many as they go about their busy lives.

We like birds: we feel serenaded by their songs, we marvel at their mastery of the air, we approve of their attention to their young, and, in certain cases, we think they taste delicious too. And birds seem to treat us with respect as we approach them they usually fly away rather than attack us or stand their ground. Some mammals may eat us, some snakes may bite us and some insects may sting us, but most birds look pretty, sound melodious and generally defer to us as we go through life. Birds are easy companions for us and can amuse and soothe us.

We also experience the world in a similar way to many birds, which adds to our feeling of kinship. Birds are creatures of sight and sound, as are we, whereas most of our fellow mammals sensations are dominated by smell and touch. We admire the bright, sometimes gaudy plumage of many male birds, and realize that so do the females of those species, and we delight in the brilliance of the finest avian songsters, and appreciate that those songs are sending messages to other birds. Birds build nests that are their temporary homes, and raise their young by guarding them from danger, keeping them warm and feeding them. They please us, intrigue us and sometimes astonish us with what they can achieve.

Birds evolved from dinosaurs in fact we can think of them as feathered dinosaurs. The fossil Archaeopteryx (from archaios, meaning ancient, and pteryx, meaning feather or wing), discovered in Germany in 1861, dates from around 150 million years ago. This early bird, which was 50 cm (20 in.) long, was covered in feathers and had broad wings and tail. It was warm-blooded and could certainly glide, and perhaps fly weakly as well; its small breastbone suggests that its flight muscles would not have been very well developed. Other proto-bird fossils have now also been identified, which push back the first known fossil feather to 160 million years.

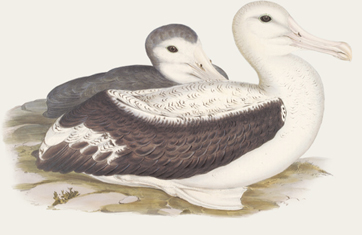

Many myths surround the enigmatic Wandering Albatross.

In those 160 million years, birds have radiated into the 10,000-plus species we see, and hear and love today. The largest surviving bird species is the Ostrich, which inhabits the plains of Africa and Arabia. It is taller than a human and, at 100 kg (220 lb), is fifty thousand times heavier than the smallest bird, the Bee Hummingbird, which weighs in at a little below 2 g (0.07 oz).

The polar wastes support very few birds although birds have been seen at both the North and South Poles while the tropical regions are richest in bird species. South America hosts 36 per cent of all land-bird species, Africa 21 per cent and Southeast Asia another 18 per cent. These figures are reflected in the numbers of bird species found in individual countries. Colombia, far from the largest country on Earth (in fact only twenty-sixth largest), has more bird species than any other more than 1,800 and its much larger neighbours, Peru and Brazil, are second and third on the list.

Hummingbirds are among the smallest birds on the planet, yet some migrate immense distances.

Every one of these bird species on our planet is remarkable in its own way, and here we have space to cover only around 67 of them. These are grouped into eight categories so that we can explore certain themes and connections in our appreciation of, and relationship with, birds, and linger over aspects of their lives in greater detail in order to celebrate them more fully. Of course, many could have fitted into more than one of our categories.

The Golden Eagle is the king of birds, and has been used to hunt wolves.

Bird song is a joy to our ears, although the early morning crow of the cockerel may be greeted with only grudging delight. In Songbirds we celebrate the beauty and variety of bird song, but also investigate its functional significance. We may pause as we go about our daily chores to listen to the sound of a singing bird, but song is energetically costly (as any chorister will confirm), and the male bird who pours his heart out is actually defending his territory and attracting a mate, both at the same time. For birds, song is deadly serious song is about sex and violence, not about joy and rapture. And yet, for us, their songs of challenge and lust are often of sublime beauty. Some birds, rather than being melodious, excel in being great mimics of other birds, but also increasingly of human-made sounds, even voices.

Birds of Prey have always been admired by mankind. They are hunters, as were our human ancestors, and they have evolved specialist skills and often incredible eyesight to be able to hunt other birds, mammals, fish and even molluscs. These are birds of majesty, whose command of the air excels that of most other birds.

The Bar-tailed Godwit makes a non-stop eight-day flight on its autumn migration from Alaska to New Zealand.

The ability to fly not only allows birds to move around quickly and directly, and to seek safe places to shelter and nest, but also means they can be great travellers. Flight enables birds to migrate immense distances and overcome barriers such as seas, deserts and mountain ranges that would be impractical on foot. Feathered Travellers describes examples of the most astounding journeys made by birds, and some of this information is only now being revealed through the use of modern technology.

Next page