While running over the Millennium Bridge toward the Tate Modern,

a path I take most mornings from my home in London, I am greeted

by hundreds of roosting black-headed gulls flanking me on both sides.

This cacophony of seabirds transports me back to my childhood by

the Cornish coast and stirs me into action for the day ahead.

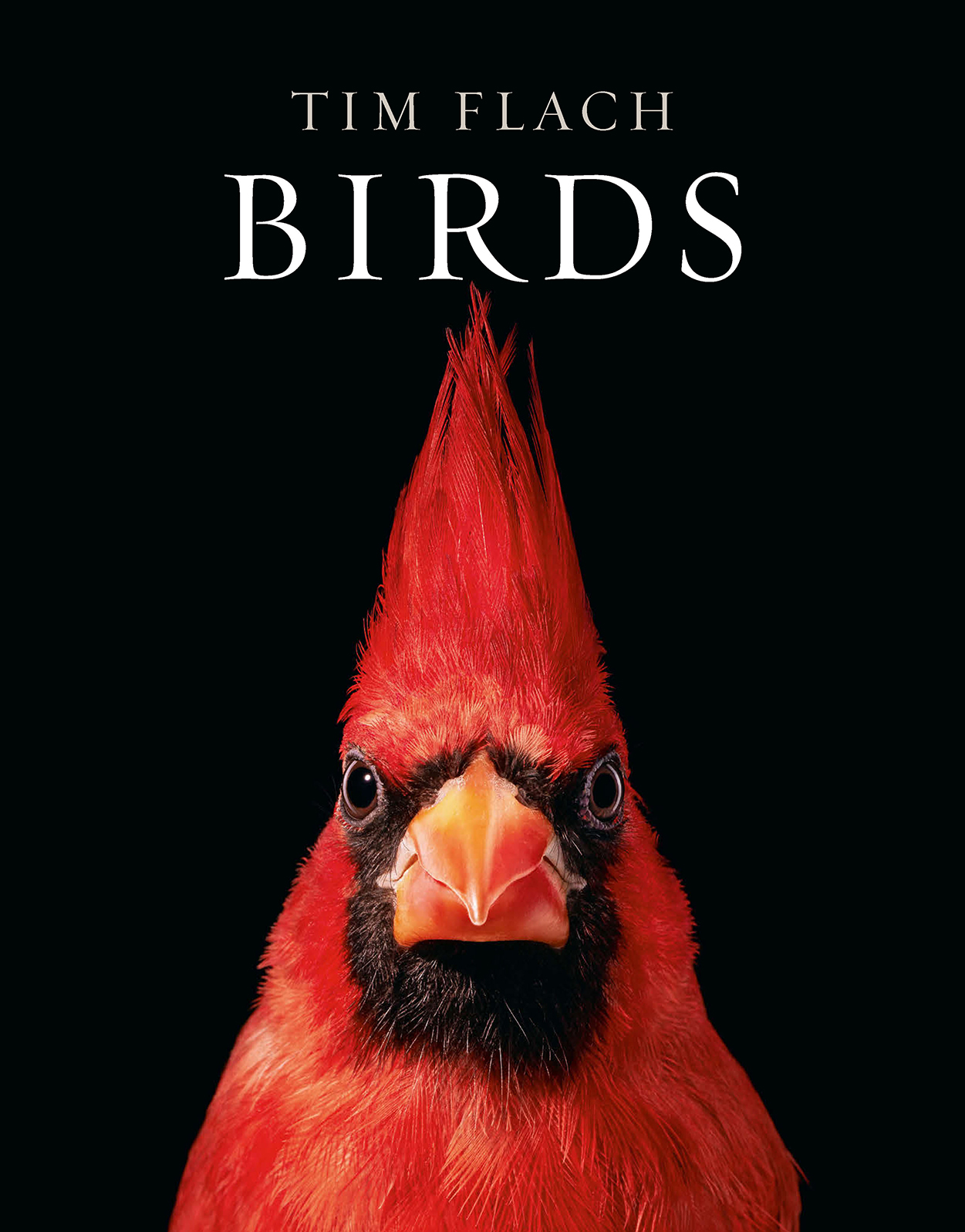

When I began this project, my intention was to explore the beauty

and wonderment of birds by depicting them in a series of portraits,

abstract and in flight. They are set against simple backgrounds to

focus on the details and illustrate their morphological diversity, and

heighten our sense of empathy.

Our journey within these pages is ordered in what is believed to be

the evolutionary sequence, beginning with the Berlin Archaeopteryx ,

a strikingly complete example of a feathered dinosaur that gives us a

direct link to the ancestors of birds today. This is followed by flightless

birds, through to the more specialized species such as hummingbirds,

and finally to poultrydomesticated and shaped by us. To craft the

chapter introductions, Yale Universitys Richard O. Prum, a leading

evolutionary ornithologist and world-renowned expert on plumage,

was the perfect fit. His knowledge and approach accentuate why

these birds have such unique plumages, colorations, and forms.

Where necessary, specialized aviaries were built to allow my subjects

to be more relaxed, oblivious to the camera and me. This encouraged

natural behavior and most importantly minimized any stress on

these captive-bred birds. In some situations, turntables were used

for rotating perches, ponds were built for ducks, and lights were

suspended high over a tank of diving penguins.

For many of us, the global pandemic has heightened our awareness

of nature and specifically birds, which have with their very presence

awakened our senses and elevated our spirits. The enforced solitude

of lockdown has also given me an opportunity to reflect on my

photographic processes and glean new inspiration from the old masters

such as Rembrandt and Turner; I have become ever more mindful of

the importance of the chiaroscuro and luminescence that they used

to such great effect. From the beginning I was aware of the legacy of

the nineteenth-century bird illustrators such as John James Audubon

and his The Birds of America , and the artists employed by John Gould.

More often than not, they had to work using only skins and taxidermy

specimens. Artists like Edward Lear did their best to observe directly

from life where possible. I like to think I work on the continuum of

this aesthetic tradition.

What photography can do uniquely as a medium is to fragment

a single moment in time, thereby extending our experience of that

moment, which the persistent flow of movement and therefore our

vision often denies us. It invites us to examine and contemplate the

bending of a feather caught in flight, the minute details of the vanes

and barbules of plumage, the frozen moments of torpedo-like diving

penguins, the painterly reflections of flamingos wading.

From the commonly seen blue tit to the critically endangered

Philippine eagle, it was difficult to decide what to include from the

more than ten thousand species of birds living today. While whittling

down the options to the

characters represented in the pages that

follow, I made some surprising discoveries, such as a distant relative

of the duck that has a unicorn-like horn (

) and a seabird

with a handlebar mustache (

). I was loaned a specimen, the

largest egg ever known, from the extinct Madagascan elephant bird,

which sat proudly on my desk for many months. It has been printed

here to scale (

) and barely fits on the page, being equivalent

in volume to about

chicken eggs.

In addition I have chosen to include, in the egg section, two poignant

extinction stories from recent history. Theres the passenger pigeon

(

), the most numerous bird species in human history,

which went from a population of billions to zero in just eighty

years. The last one, known as Martha, died on September

,

1914

,

in Cincinnati Zoo. Then theres the great auk (page

), a large

penguin-like species (although no relation to penguins) found in the

northern hemisphere, that once numbered in the millions. The last

pair were taken and unceremoniously strangled to death at the request

of a Danish museum curator on June

,

1844

. These now extinct

species are a tragic reminder of the potential future faced by others.

To help me traverse the vast landscape of the avian world, I was

fortunate to have my very own bird whisperer, Daniel Cullen,

join me in the adventure as producer and handler. Daniel has

dedicated his whole life to working with birds and generously

sharing his wisdom, and he was a guiding force in my journey of

discovery. He advised on the design of purpose-built aviaries, the

timings when each species would be in peak condition, and the

representation of the various groupings. We were fortunate to have

access to the very best avian collections in the world, both public