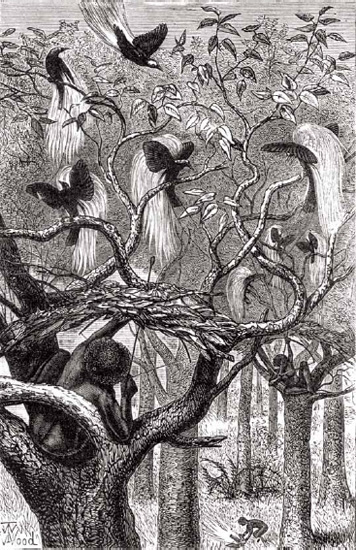

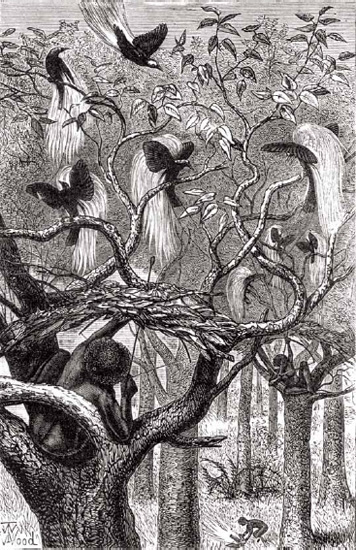

Papuans hunting the Greater Bird of Paradise on the Aru Islands. Engraving by T. W. Wood for A. R. Wallaces celebrated book The Malay Archipelago (1869). The picture is misleading in that the plumes of the displaying birds are shown as if sprouting from above, instead of beneath the wings.

Nature seems to have taken every precaution that these, her choicest treasures, may not lose value by being too easily obtained. First we find an open, harbourless, inhospitable coast, exposed to the full swell of the Pacific Ocean; next, a rugged and mountainous country, covered with dense forests, offering in its swamps and precipices and serrated ridges an almost impassable barrier to the central regions; and lastly, a race of the most savage and ruthless character.... In such a country and among such a people are found these wonderful productions of nature. In those trackless wilds do they display that exquisite beauty and that marvellous development of plumage, calculated to excite admiration and astonishment among the most civilized and most intellectual races of man ...

Alfred Russel Wallace. Narrative of Search after Birds of Paradise, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (1862).

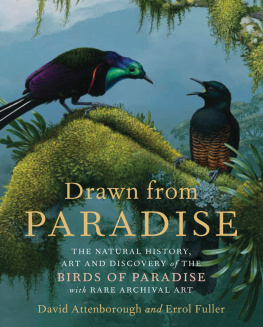

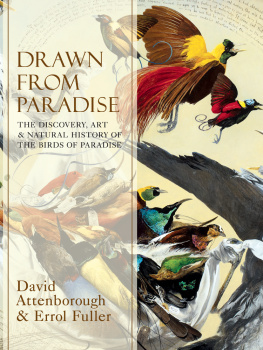

End to the Squandering of Beauty (Entry of the Birds of Paradise into Western Thought). Raymond Ching, August to December, 2011.Oils on canvas, 180 cm x 240 cm (6 ft x 8 ft).

Two or three [men of Aru, New Guinea] begged me for the twentieth time to tell them the name of my country. Then, as they could not pronounce it... they insisted I was deceiving them, that it was a name of my own invention. One old man... was... indignant. Ung-lung! said he. Who ever heard of such a name? Ang lang, that cant be the name of your country Then he tried to give a convincing illustration. My country is Wanumbai anybody can say Wanumbai. But N-glung! Who ever heard of such a name? Do tell us the real name of your country... then when you are gone we shall know how to talk about you. The whole party remained convinced I was deceiving them. They then attacked me on another point what all the animals and birds... were preserved so carefully for. I tried to explain... that they would be stuffed, and made to look as if alive, and people in my country would go to look at them. But this was not satisfying; in my country there must be many better things to look at... They [the Aru men] did not want to look at them [the birds]; and we, who made calico and glass and knives, and all sorts of wonderful things, could not want things from Aru to look at.... The old man said to me, in a low, mysterious voice, What becomes of them when you go on to the sea? Why, they are all packed up in boxes, said I. What did you think became of them? They all come to life again, dont they? said he... and he kept repeating, with an air of deep conviction, Yes, they all come to life again, thats what they do they all come to life again.

Alfred Russel Wallace. The Malay Archipelago (1869).

Arfak Six-wired Bird of Paradise. John Latham, c.1780. Watercolour, 15 cm x 12 cm (6 in x 5 in). The Natural History Museum, London.

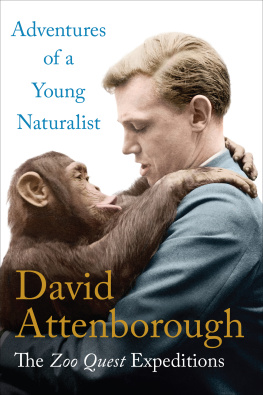

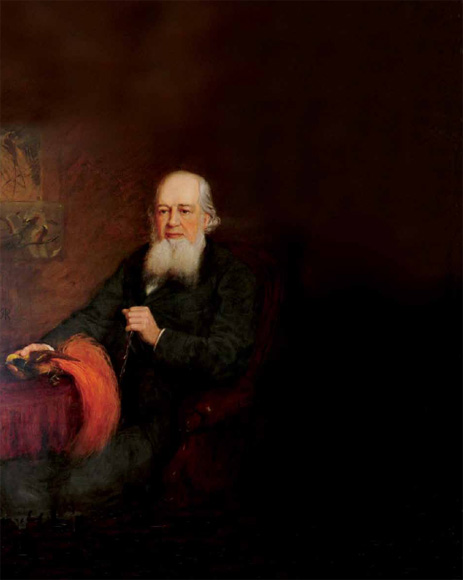

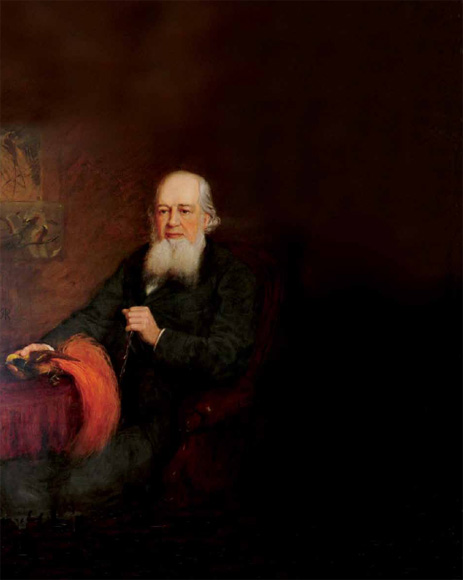

John Gould with a specimen of Count Raggis Bird of Paradise H. R. Robertson, 1878. Oils on canvas. Private collection.

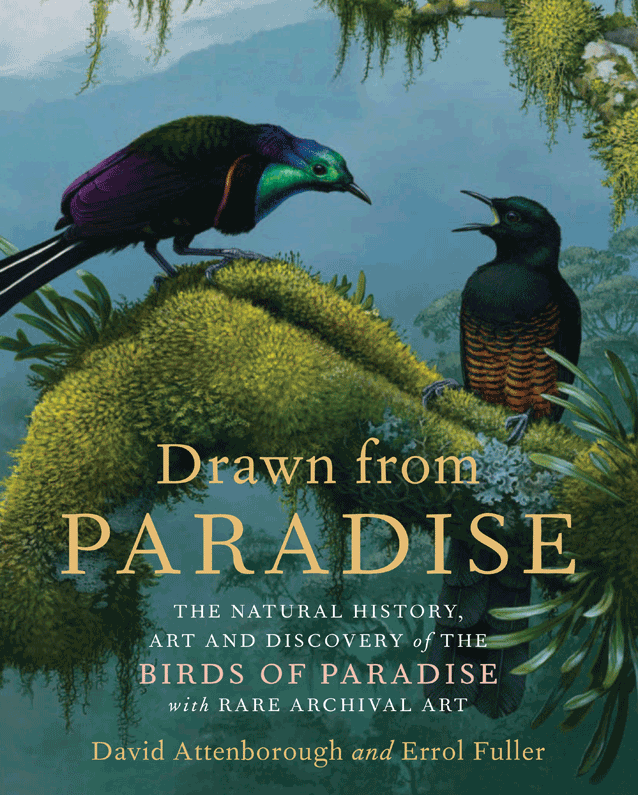

CONTENTS

Feathers from Paradise. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour, 52 cm x 38 cm (21 in x 15 in). Private collection.

To the human eye, birds are among the most beautiful and intriguing of all natures creations. Even a single stray feather, picked up by chance on a country walk, is a thing of wonder if examined closely. Its form, delicacy, and its colouring sometimes subdued, sometimes gaudy each have the power to astonish. And even the most familiar of species the soberly dressed house sparrow or the common starling, for instance are creatures of subtle beauty when viewed with fresh eyes.

There are, of course, whole families of birds well known for the astonishing visual impact of their plumage. Take, for example, the pheasant family. It boasts many spectacularly coloured species the peacock, the tragopans and monals, or even the common pheasant itself that defy description in words. Many other families contain kinds that are equally remarkable.

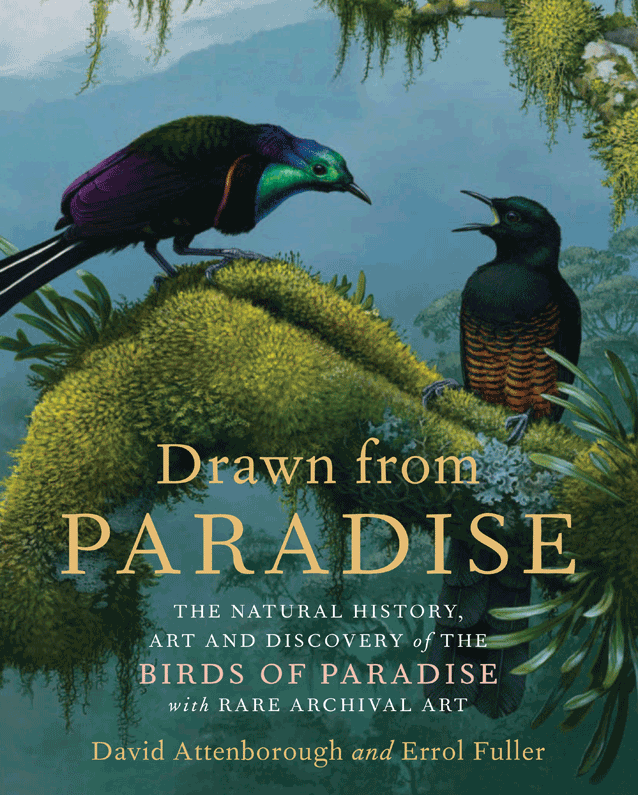

But one family stands out from the rest, not just because of the exquisite appearance of many of its species, but also because of the sheer extravagance of variety, colour and form that these creatures parade. These are birds that truly live up to their name: birds of paradise.

From the moment of their introduction to the European mind in the early sixteenth century, their unique beauty was recognised and commemorated in the first name that they were given; birds so beautiful must be birds from paradise! This naming extravaganza even continued into the nineteenth century when newly discovered species were named after illustrious crowned heads of Europe Prince Rudolphs Blue Bird of Paradise, Princess Stephanies Bird of Paradise, the Emperor of Germanys Bird of Paradise. The list of royal names goes on and on. Nor were splendid names enough to satisfy the inquiring minds of those who encountered the birds. In the early days all manner of fanciful stories and theories grew up to explain the mystery of their phenomenally beautiful appearance, and the tales quickly acquired mythical status. And as far as mystery is concerned, these birds are still wrapped in enigma.

King Bird of Paradise, male. Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour. 52 cm x 38 cm (21 in x 15 in). Private collection.

Of course, we now know much more than the European scholars of the early sixteenth century who received the first specimens from the then remote lands somewhere far to the east. But there is much that is still unknown.

Next page