David Attenborough - Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth

Here you can read online David Attenborough - Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

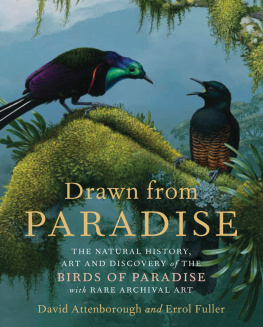

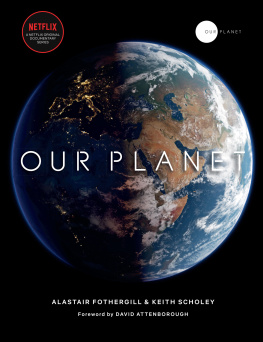

David Attenborough is one of the worlds leading naturalists and broadcasters. His distinguished career spans more than sixty years, and his extraordinary contribution to natural history broadcasting and film-making has brought him international recognition, from Life on Earth to Frozen Planet, Planet Earth to Blue Planet. He has achieved many professional awards, honours and merits, including the CBE and OM, and was knighted in 1985.

My debts in writing the first edition of this book were many and large. Most importantly they were to the BBC production team, headed by Richard Brock, with whom the initial scripts were debated. On many occasions, those involved editorially suggested new and unfamiliar creatures to replace the better-known examples that I had first thought of and pointed out gaps and misapprehensions in my initial drafts. I was and still am grateful to them all including not only producers and directors, but researchers, sound recordists and camera operators.

In writing both the film scripts and the chapters for this book, I relied greatly on the innumerable scientists who laboured to piece together coherent descriptions of animal communities and painstakingly elucidated the way in which they function. For the most part I learned of their insights and discoveries from their writings in specialist journals, but in some fortunate instances, we were lucky enough to work with such researchers in the field. On every occasion when that happened, we were met with the most generous and uninhibited help, for which we were all deeply grateful. Many assisted us in very practical ways with the skills that can only come from long periods spent in the field, and some of them helped us to see things that only they could have led us to. In particular I would like to thank Dr. Jim Stevenson in Aldabra; Dr Nigel Bonner and Peter Prince in Antarctica; Dr Norman Duke in Australia: Dr. Francis Howarth in Hawaii; Dr Putra Sastrawan in Indonesia; Truman Young in Kenya; Dr Mary Seely in Namibia; Dick Veitch in New Zealand; Dr Felipe Benevides in Peru; and Gary Alt, Professor John Edwards, Prof. Charles Lowe and Prof. Robert Paine in the United States of America. Dr. Robert Attenborough, Dr. Humphrey Greenwood, Gren Lucas and Dr. L Harrison Matthews were kind enough to read individual chapters and steer me away from error.

I am also most grateful to Myles Archibald of William Collins Publishers who suggested that there should be a new edition of the book and to Tom Cabot and Rachelle Morris who brought together the photographs with which it is illustrated.

A great deal has happened to our planet since this book was written. Some of the warnings given in the first edition have proved to be only too accurate. Other newer dangers have also appeared. Professor Matthew Cobb of Liverpool University has therefore read the entire text to ensure that it is still accurate. But this books aim was not, and is not, to warn of the damage that we have inflicted on the planet. Nor is it to describe what actions must be taken if we are to allow the ecosystems of the world to survive in all their complexity. I have written about those issues elsewhere. This book is different. It is to try to describe the communities of animals and planets its ecosystems so that we can understand how they work. Only if we have such understanding will be able to repair the damage we have done to our planet and I thank all those I have mentioned here and many I have not for their help in trying to do so.

T he titanic forces that built the Himalayas and all the other mountains on earth proceed so slowly that they are normally invisible to our eyes. But occasionally they burst into the most dramatic displays of force that the world can show. The earth begins to shake and the land explodes.

If the lava that erupts from the ground is basalt, black and heavy, then the area may have been continuously active for many centuries. Iceland is just such a place. Almost every year there is volcanic activity of some kind. Molten rock spills out from huge cracks that run right across the island. Often it is an ugly tide of hot basalt boulders that advances over the land in a creeping unstoppable flood. It creaks as the rocks cool and crack. It rattles as lumps tumble from its front edge. Sometimes the basalt is more liquid. Then a fountain of fire, orange red at the sides, piercing yellow at its centre, may spout 50 metres into the air with a sustained roar, like a gigantic jet engine. Molten basalt splashes around the vent. Lava froth is thrown high above the main plume where the howling wind catches it, cools it and blows it away to coat distant rocks with layers of grey prickly grit. If you approach upwind, much of the heat as well as the ash is blown away from you, so that you can stand within 50 metres of the vent without scorching your face, though when the wind veers, ash will begin to fall around you and large red-hot lumps land with a thud and a sizzle in the snow nearby. You must then either keep a sharp eye out for flying boulders or run for it.

Flows of cooling black lava stretch all round the vent. Walking over the corded, blistered surface, you can see in the cracks that, only a few inches beneath, it is still red hot. Here and there, gas within the lava has formed an immense bubble, the roof of which is so thin that it can easily collapse beneath your boot with a splintering crash. If, as well as such alarms, you also find yourself fighting for breath because of unseen, unsmelt poisonous gas, you will be wise to go no further. But you may now be close enough to see the most awesome sight of all a lava river. The liquid rock surges up from the vent with such force that it forms a trembling dome. From there it gushes in a torrent, 20 metres across maybe, and streams down the slope at an astonishing speed, sometimes as much as 100 kilometres an hour. As night falls, this extraordinary scarlet river illuminates everything around it a baleful red. Its incandescent surface spurts bubbles of gas and the air above it trembles with the heat. Within a few hundred yards of its source, the edges of the flow have cooled sufficiently to solidify, so now the scarlet river runs between banks of black rock. Farther down still, the surface of the flow begins to skin over. But beneath this solid roof the lava surges on and will continue to do so for several miles more, for not only does basaltic lava remain liquid at comparatively low temperatures, but the walls and ceiling of solid rock that now surround it act as insulators, keeping in the heat. When, after days or weeks, the supply of lava from the vent stops, the river continues to flow downwards until the tunnel is drained, leaving behind it a great winding cavern. These lava tubes, as they are called, may be as high as 10 metres and run for several kilometres up the core of a lava flow. In a striking example of how similar processes produce similar effects, lava tubes are even found on the Moon and on Mars.

Iceland is one of a chain of volcanic islands that runs right down the centre of the Atlantic Ocean. Northwards lies Jan Mayen; to the south, the Azores, Ascension, St Helena and Tristan da Cunha. The chain is more continuous than most maps show, for other volcanoes are erupting below the surface of the sea. All of them lie on one great ridge of volcanic rocks that runs roughly midway between Europe and Africa to the east, and the Americas to the west. Samples taken from the ocean floor on either side of the ridge show that, beneath the layers of ooze, the rock is basalt, like that erupting from the volcanoes. Basalt can be dated by chemical analysis and we now know that the farther away from the mid-ocean ridge a sample is taken, the older it is. The ridge volcanoes, in fact, are creating the ocean floor which is slowly growing away from them, on either side of the ridge.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth»

Look at similar books to Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Living Planet : The Web of Life on Earth and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.