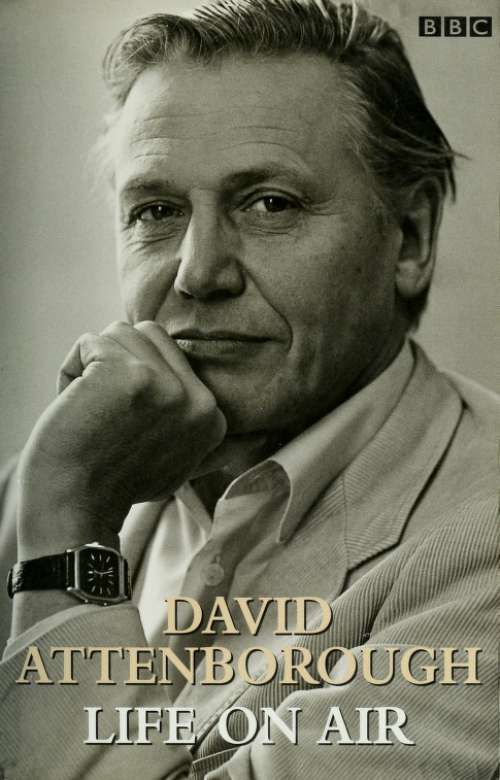

David Attenborough - Life on Air

Here you can read online David Attenborough - Life on Air full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, publisher: London : BBC Worldwide, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Life on Air

- Author:

- Publisher:London : BBC Worldwide

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life on Air: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Life on Air" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Life on Air — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Life on Air" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

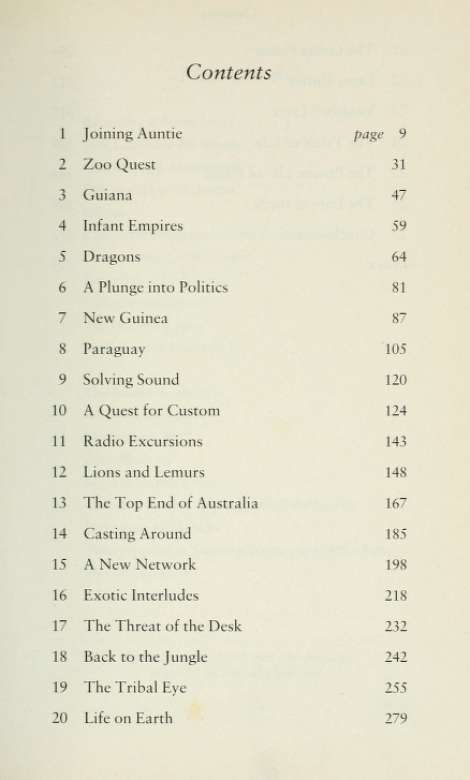

Contents

21 The Living Planet 294

22 Extra Duties 313

23 Vanished Lives 317

24 The Trials of Life 326

25 The Private Life of Plants 344

26 The Lure of Birds 359

27 Conclusions 372 Index 375

Recording in Sierra Leone

Jack Lester and Alf Woods

Charles Lagus filming ants

Our first Komodo dragon

Sabran

Charlie the orangutan, on the Kruwing

Dance at Minj, New Guinea

Butterflies at Ihrevu-qua

Oiling up for the swim

The swimming party

Land-diver on Pentecost Is.

The Adamsons and Elsa With Elsa the lioness New regime, BBC Dressing down Moro in his cult house

Bested by gorillas (photographs, John Sparks) Dinosaurs in Colorado

Amorphophallus, Sumatra (photograph, Mike Pitts) Men and penguins A kiwi at night

All pictures property of David Attenborough, except where otherwise indicated

Joining Auntie

The clock on the south-western tower of St Paul's cathedral appeared to have stopped. I could just see it if I craned my neck and peered out of the very side of my office window. Maybe it was suffering from a delayed shock after the Blitz. It was, after all, 1950 and the war had only been over for five years. But ten past two, which was what the clock's hands indicated, could hardly be the correct time. I had eaten my sandwich lunch in the garden on the bomb-site just over the road and had been back at my desk promptly at two o'clock, as befitted the most junior and recently recruited member of the London publishing house for which I was working. And that seemed at least three-quarters of an hour ago.

I turned my attention to the galley proofs in front of me. It was a text about tadpoles for primary schools. Interesting in its own way but hardly, I felt, the sort of work that taxed my hard-won degree in natural sciences. Fitting in the illustrations, using a technology that had not changed significantly since Gutenberg's times, required counting the words, sometimes even the individual letters. I had to tot them up, work out how many would have to be carried forward to the next page and then wrestle with the various possibilities for trimming the next illustration.

Another half hour of this and I took another glance through the window. The clock hadn't stopped after all. Its hands had certainly moved. They had advanced a few minutes. But it was still not half past. This dismal revelation depressed me so much that I decided to turn my desk around so that I wasn't hypnotised by the hands of a clock. Instead, I stared at a blank wall. And it was then that I decided that this was not the way I wanted to spend the rest of my life. Maybe my future was not, after all, to be a gentleman publisher.

But what was it? I was twenty-four. I had studied natural sciences at Cambridge, thinking that somehow research would ultimately take me to remote and exciting parts of the world. Then I had to do my national service. I went into the Navy hoping that I might be sent somewhere romantic. At Gosport, where we did our preliminary training, I met old naval hands who talked a lot about 'Trinco' that is to say, Trincomalee in

Joining Auntie

what was then Ceylon. The Far Eastern Fleet was based there. It sounded good to me and I told whoever I thought might have some influence in the matter that Trinco was just the sort of place I would like to be posted, at the end of my training. In the event, I was sent to join an aircraft carrier that was being mothballed as part of the Reserve Fleet in the Firth of Forth.

By the time the Navy had finished with me, I had decided that I did not want to go back to university to read for a doctorate. Zoological research in those days was largely laboratory-bound and that wasn't the way I wanted to study animals. In any case, I had now married Jane, whom I had met at university, and I didn't fancy going back to subsist on a student grant, even if I could have got one. So I had decided that publishing would suit me, and had got myself a job as a junior editorial assistant with an educational publisher. But now that didn't seem to be a thrilling proposition either.

I consulted the appointments columns in The Times, which, as an embryonic city gent, I felt I had to carry to the office daily and occasionally read. There I saw an advertisement by the BBC for a radio talks producer. Since I had failed to find a job that would take me to remote places, I thought I might enjoy that sensation, second-hand, by seeking out people who had managed to do so and getting them to talk about it. So I applied. A couple of weeks later I got a polite note telling me that the job had gone elsewhere. I returned to my galley proofs and my tadpoles.

Then, to my surprise and embarrassment, I got a telephone call at the office. Personal calls were not approved of and I felt slightly criminal as I listened to a lady from the BBC. She explained that her name was Mary Adams and that she was not from Radio but from the Corporation's Television Service. She had seen my application form and although I hadn't been summoned by Radio for an interview, she nonetheless felt that I might be the right sort of person for Television. Was I interested? I had to confess that I hadn't actually seen much television. I had once watched a television play in my wife's parents' house, but they were the only people I knew with a set and I certainly had not got one myself. Mrs Adams didn't think that was necessarily a disadvantage. Would I like to call upon her to discuss the possibility of joining a training course? So I applied to my employers for one day's leave of absence to be deducted from my annual fourteen-day holiday and went up to Alexandra Palace in North London to visit Mrs Adams.

Alexandra Palace was - and still is - a sprawling Edwardian building, built on the top of a hill surrounded by a park in the north-eastern

Joining Auntie

suburbs of London. It has a huge hall that had been built as a concert hall and fitted with a colossal organ, but had since done service as a ballroom, an ice rink and a glorified village hall, and then become semi-derelict. All around it were blocks with rooms for offices. One of these had been modified to accommodate two small television studios. On the tower above them stood a tall pylon-like transmitter from which the world's first public television signals had been radiated in 1936. Immediately beneath it Mrs Adams had her office.

She was in her mid-fifties, grey-haired, affable, with a smoker's cough, a darting glance and a heartening guffaw. I subsequently discovered that she was the widow of a Member of Parliament who, had he lived, seemed destined for a glittering parliamentary career. She had been educated as a geneticist at Oxford University before the war but had left academia to join BBC Radio's Further Education Department. She had had a hand in some of the very first television programmes. After the war she had rejoined television as an administrator with the task of building from scratch a department called, perhaps oddly for television, 'Talks'.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Life on Air»

Look at similar books to Life on Air. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Life on Air and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.