First published in Great Britain in 2017

by Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2017

Excerpt from The Restaurant at the End of the Universe by Douglas Adams, reproduced with the permission of the Licensor through PLSclear and Ed Victor Ltd.

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publisher, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-840-3 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-841-0 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

Follow us on Twitter @OMaraBooks

Cover design: Anna Morrison

C ONTENTS

I have only once in my broadcasting career asked if I could be released from a commitment to make a television programme. That was over forty years ago. I had, a few years earlier, as Controller of BBC2, arranged for the Royal Institutions Christmas Lectures to be broadcast on that network. But now I had resigned from that job to resume making programmes and had recklessly agreed to give one of these annual lecture series myself.

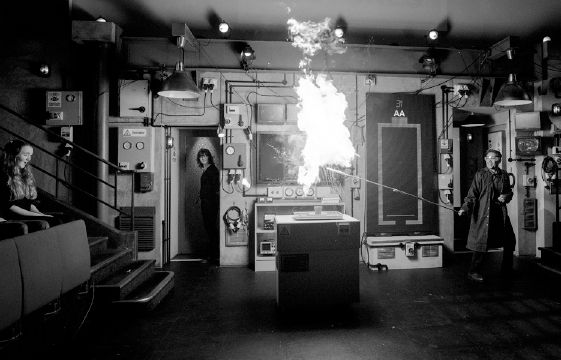

When commissioning the broadcasts, I had stipulated that they were to be transmitted live and unedited, exactly as they were performed. It would add to the fizz and excitement, I thought, if the television audience knew that the experiments really were experiments and that no one could be totally certain of what was going to happen. Now, about to give a series myself, I had to abide by that rule. To make matters worse, I had selected a zoological subject and said I would illustrate it with demonstrations involving wild and unpredictable animals.

I started work on the first programme and it very soon became clear to me that the task was impossible. How could you be sure that the animals would behave in the way that theory dictated? How could I be certain that they wouldnt bite me? Or escape? I laboured away at my script for the first Lecture, trying to get my explanations clear and my experiments accident-proof, at the same time haunted by the thought that I only had the vaguest idea of what the second would be about and no idea whatsoever about the content of the remaining four, apart from their titles. And the series was due to start in a few weeks time.

So I telephoned the BBC producer to tell him that I wished to be released from my contract. Nonsense, he said. I seem to recall that I then offered to make a penalty payment for breaking my contract. He rejected that in similar terms, as I would have expected any producer worth his salt to do when dealing with a nervous contributor. You will get some idea of the result in the seventh chapter of this book.

The Lectures are no longer shown live, as they happen. Perhaps that is just as well from the Lecturers point of view. But it also suits the television programme planners to be able to show the programmes at a time that suits their schedules and not, of necessity, when they are actually delivered. Nonetheless, I dare say you will marvel at the extraordinary skill and ingenuity with which all my co-contributors devised such dazzling, entertaining and informative experiments and stimulate such interesting thoughts in the minds of their audience. As indeed, I do. But only I and they know the full extent of what it can cost to give them.

A few steps away from the busy streets of central London theres a room thats familiar to millions of people around the world; the steep rows of seats, the polished woodblock floor, the large desk. Each year for nearly two hundred years, a scientist has walked into this room to enthuse and enlighten the young audiences who flock to the Lecture Theatre for the Royal Institution (RI) Christmas Lectures. People have watched them on television since 1966 and now Lectures past and present are available to watch online. And after the London Lectures are finished, many of the Lecturers go on tour to entertain audiences from South America to Asia. The founder of the series, the influential British scientist Michael Faraday, would no doubt be astounded to know the Lectures continue today and reach so many people worldwide.

This is the second book celebrating the RIs Christmas Lectures. The first, 13 Journeys Through Space and Time, took us on a voyage of astronomical discovery and gazed into the solar system and beyond. Now we set off to explore the living wonders of our own planet.

A succession of eminent speakers have filled the Lecture Theatre with a teeming array of furry mammals, luxuriant plants, squawking birds, crawling insects and plenty more besides, as they unlock many of the greatest secrets of life on earth. The book begins in the early twentieth century, a time when studies of the living world were gradually shifting away from a descriptive discipline (preoccupied mainly with finding and naming species) towards the modern science of ecology. Instead of studying organisms in isolation, scientists began to consider the ways living creatures interact with each other and their environment, forming an intricate web of life.

Michael Faraday himself might have been surprised by the topics covered here. Since their inception in 1825 and throughout the nineteenth century, few of the RI Christmas Lectures have focused on the living world. There was one Lecture in 1831 by the Scottish naturalist James Rennie simply entitled Zoology and another, Botany, by John Lindley in 1833 (but there is very little archive material to provide details of either). Otherwise, the Lectures tended to concentrate on the physical sciences. Even Charles Darwins groundbreaking 1859 theory of evolution by natural selection explaining how life on earth came to be didnt feature in any nineteenth-century Lectures. Richard Dawkins first tackled evolution in the Christmas Lectures in 1991 (see ); perhaps the topic was deemed unsuitable and too controversial for young Victorian audiences.

The Lectures covered in this book represent something of a new generation of Christmas Lecturers. They reflect the growing interest over the last century in understanding how the living world works, together with mounting concerns that human actions are damaging the living systems on which we all depend in so many ways.

Each chapter focuses on a particular Lecture series, which consisted of between three and six hour-long talks originally delivered on several days over the festive period. The aim of the book is to give a flavour of the most exciting discoveries and ideas discussed by each Lecturer and to transport readers on an exploration into the wilds. Well see how scientists have solved many remarkable mysteries of the living world and revealed ever-greater wonders, from tropical rainforests and the coldest place on earth, to the familiar animals and plants we see in the world around us every day.