Table of Contents

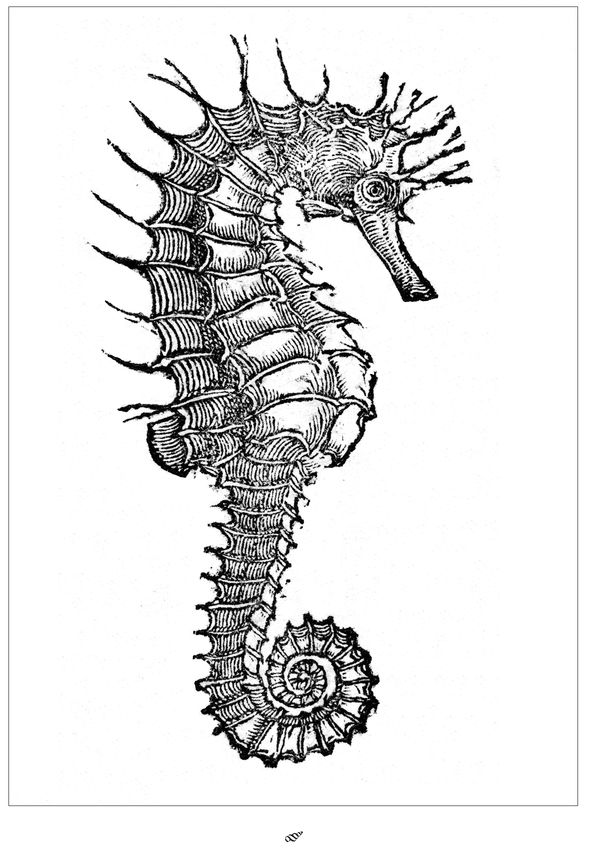

Seahorse woodcut from Guillaume Rondelets 16th century

Libri de Piscibus Marinis

Credit: Guillaume Rondelet, c. 1555. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of

Cambridge University Library. CCA. 46. 45

For my Mum and Dad,

and for Ivan

PRELUDE

And the Sea-horse, through the ocean

Yield him no domestic cave,

Slumbers without sense of motion,

Couched upon the rocking wave

William Wordsworth, Song for the Wandering Jew, 1827

Peer at a seahorse, briefly hold one up to the light, and you will see a most unlikely creature, something that you would hardly believe was real were it not lying there in the palm of your hand, squirming for water. Should we presume these odd-looking creatures were designed by a mischievous god who had some time on her hands? Rummaging through a box labeled spare parts she finds a horses head and, feeling a desire for experimentation, places it on top of the pouched torso of a kangaroo. This playful god adds a pair of swiveling chameleon eyes and the prehensile tail of a tree-dwelling monkey for embellishmentthen she stands back to admire her work. Not bad, but how about a suit of magical color-changing armor, a perfect fit, and a crown borrowed from a fairy princess, shaped as intricately and uniquely as a human fingerprint? Shrink it all down to the size of a chess piece and the new creature is complete.

No matter how tempting such a strange tale of creation may be, seahorses are real creatures, a product of natural selection. They inhabit a wide stretch of the oceans and are not, as we might suppose, restricted to warm azure waters that lap on equatorial shores. If you stand with your toes dabbling in shallow sea almost anywhere in the worldexcept for the iciest spots where your feet would freezethere is a chance you might see a seahorse. Not a very great chance, admittedly, but a chance nonetheless.

What is it that makes seahorses seem so special, like miniature dragons of the sea? Where does their peculiar appearance come from, why do they look like nothing else on earth? What goes on during a day in the life of a seahorse? And how did they evolve to be the only species in the world in which males give birth?

As a marine biologist, I tinker with these sorts of questions, the questions that fascinate me and occasionally keep me awake at night and certainly move me to do the things I do.

On an inauspicious day hemmed in beneath low gray skies I stood, aged sixteen, on the shores of a flooded gravel pit in the British Midlands and decided what I wanted to be. I had just returned from my first dive in open watermy first underwater foray away from the sterile chlorination of the swimming pool, a chance to put months of training into practice. The greatest shock on that dive had been the first thirty seconds as the terrifying cold crept in through the cuffs of my inelegant, thick semi-dry suitthere was obviously nothing dry about mine. A single fuzzy notion stammered around my gradually freezing brain: Do people really do this for fun? It wasnt long before my inexperienced feet drifted too close to the squidgy pit bottom, stirring up a turbid brown haze and adding vision to my list of rapidly vanishing senses. Only then was it obvious why my instructor had insisted on tethering me to him with a plastic cord, like a dog on a leash. I couldnt see my hand in front of my face, let alone another diver a few feet away. After relentless, perishing minutes of wishing this whole dreadful business could be over and forgotten, something happened that instantly made it all worthwhile. Through a parting in the murky water I saw a fish. It wasnt a particularly pretty fish, just small and silvery and, frankly, quite normal-looking. But even so, it was a wild fish and I was sharing its three-dimensional aquatic realm. Despite the rowdy bubbling of my human exhalations and my amplified clumsiness in the numbing cold, I caught a brief, glorious glimpse of what it is like to be a fish. All it took was this single unremarkable fish to hook me in, utterly and irretrievably, and transform me into a marine biologist in the making.

Picture, then, what went through my mind eighteen months later when, as a fully qualified diver, I leapt into tropical waters for the first time. The sea off Belize was warm like a bath and so clear I could see the coral reef spread out around me in every direction for thirty meters or more. With childlike glee, I frolicked through a vibrant, kaleidoscopic sweet shop. Electric blue fish darted between glowing lime-green towers of sponges. Shoals of snappers, with banana yellow stripes, spilled over the reef edge into the bottomless cobalt depths. The color blue has never held such meaning to me, a line in my dive logbook reads. For eight blissful weeks I camped on a desert island, learned how to identify corals and fish, and spent hours exploring and studying a submerged wonderland. I met my first sharks and sea turtles, swam with stingrays that were bigger than me and I watched, speechless, as flying fish leapt from their watery realm and skittered across the tops of the waves. That trip confirmed my instinct on seeing that first fish back in the British gravel pit: Marine biology was for me. It was also in Belize that I first became preoccupied with the idea of seeing a particular group of aquatic animals. Of all the hundreds of thousands of fish that live in the seas, I quickly realized it was the seahorses I wanted to see the most. Something about them felt subtly irresistible to me, something to do with their perplexing appearance tangled up in my longing to understand their obscure lives. From then on, no matter where I went diving or what I was supposed to be doing while I was down there, I began to keep an eye out for the silhouette of a down-turned snout or the twitch of a chameleon-like eye. But I was going to have to wait a long time before my first encounter with a wild seahorse.

In the years that followed my induction into the tropics, through countless semesters of university study, summer vacation work, and research jobs around the world, my head filled up with a medley of marine encounters, each one deepening my devotion to the oceans. After finishing high school, I delayed my entry to university for a year, grabbing the opportunities that a gap year would offer me to explore my beloved marine domain. While planning my travels, I watched a TV documentary about whale sharks and was instantly determined to see one for myself. I set off for Australias remote west coast, offering my services as a volunteer with a whale shark research group, and in a rendezvous I will never forget, found myself swimming alongside the undisputed emperor of the fish world. Over there, the boat captain shouted above the puttering of the engine, waving his arm across the choppy Indian Ocean waves. I couldnt see a thing as I jumped in the water and kicked as hard as I could in the vague direction of his gesture. Whale sharks are big, monstrously so, and nothing can prepare you for seeing one up close; being in the water next to one creates a diminutive feeling like no other. It steamed toward me like a train. I wasnt scared it would run me down or eat me; they are, after all, harmless plankton feeders. I was simply staggered that it was getting closer and closer and still there was no end in sight. As its wide square jaw approached, it peered at me with a deep-set piggy eye. Its inky-blue skin, stippled in fist-size white spots, slid past me like an unending conveyor belt, until eventually its scythe like tail fin planed into view; the tail alone was taller than I was, even with my dive fins on. I felt honored and belittled by the brief moments we spent together, before it powered off, too fast for me to keep up.