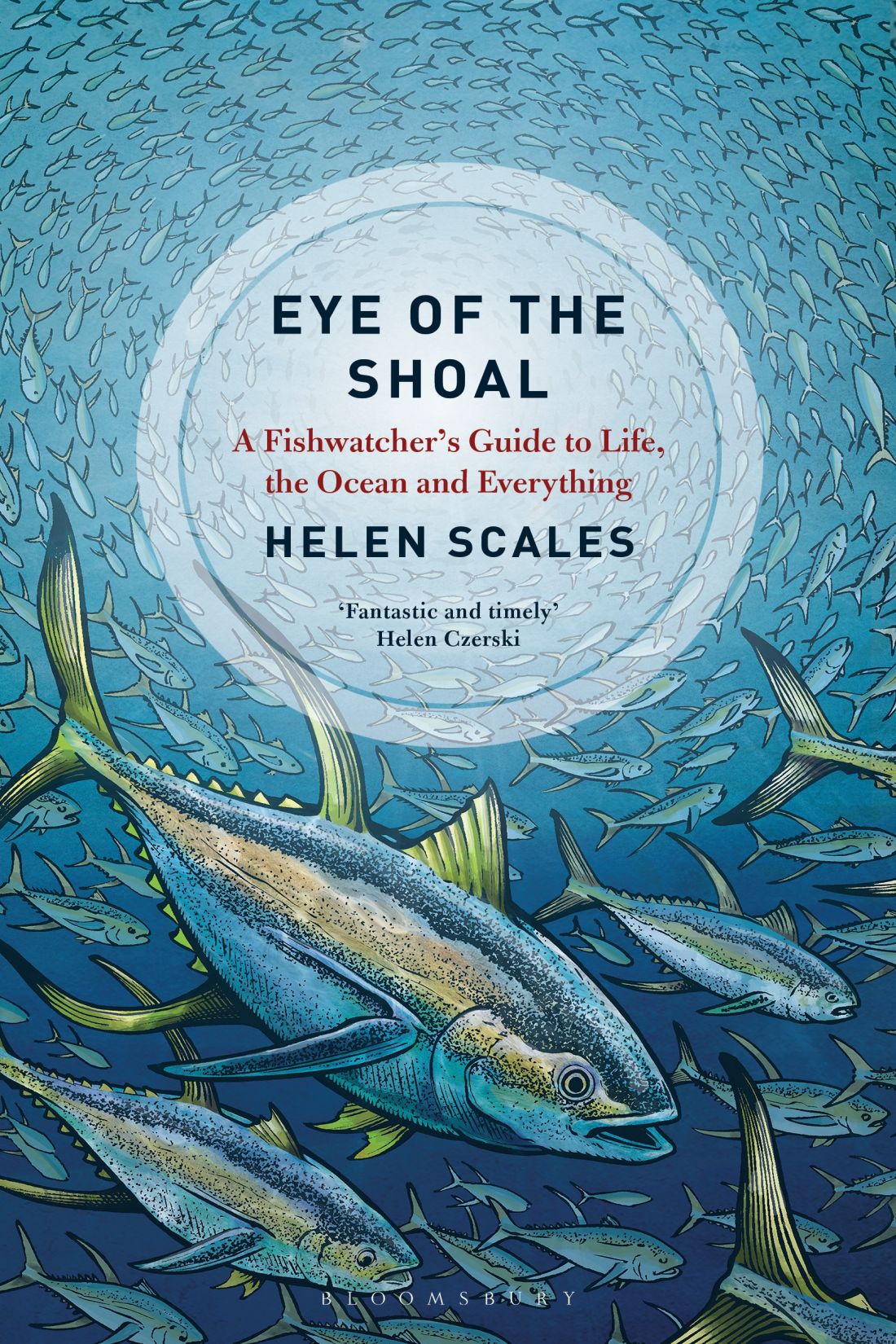

Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

p53: The Gene that Cracked the Cancer Code by Sue Armstrong

Atoms Under the Floorboards by Chris Woodford

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

Chilled by Tom Jackson

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Breaking the Chains of Gravity by Amy Shira Teitel

Suspicious Minds by Rob Brotherton

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Electronic Dreams by Tom Lean

Sorting the Beef from the Bull by Richard Evershed and Nicola Temple

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Furry Logic by Matin Durrani and Liz Kalaugher

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

My European Family by Karin Bojs

4th Rock from the Sun by Nicky Jenner

Patient H69 by Vanessa Potter

Catching Breath by Kathryn Lougheed

PIG/PORK by Pa Spry-Marqus

The Planet Factory by Elizabeth Tasker

Wonders Beyond Numbers by Johnny Ball

Immune by Catherine Carver

I, Mammal by Liam Drew

Reinventing the Wheel by Bronwen and Francis Percival

Making the Monster by Kathryn Harkup

Best Before by Nicola Temple

Catching Stardust by Natalie Starkey

Seeds of Science by Mark Lynas

Outnumbered by David Sumpter

For Celia and Peter, Katie and Maddie,

with memories of Ningaloo.

Contents

Daylight fades, and a shoal of fish settles down for the night in a quiet pool in the Amazon rainforest. The fish are small, no bigger than your thumb to the knuckle, with forked tails, a golden body stripe and a red streak above each eye. They hide among the submerged, mouldering leaves that fell from the canopy high above, and theyve all been tricked by a subtle message: this is not a fish . A leaf drifts towards the shoal. Like all the other leaves, its brown and blotched; it even has a stalk at one end, where it was once apparently attached to a tree. But then, in an instant, jaws fling open and a huge mouth gulps and swallows a member of the oblivious shoal. Half a second later the Amazon Leaf-fish is once again a leaf.

Elsewhere in Amazonia, a male Splash Tetra with large pearly scales and red-tipped fins hangs patiently under a promising frond of vegetation, waiting for a female to show up and, hopefully, choose him as a mate. If she does, the pair will leap from the water and stick themselves to a leaf, clinging with suckers on their fins. The female will lay eggs, a dozen or so at a time, and the male will fertilise them with a squirt of sperm. Then they will both tumble back into the water. Splash Tetras keep doing this, jumping and falling again and again, until theyve laid and fertilised at least 200 eggs in a dense clutch. Then the exhausted female will swim off, leaving her babies stuck to their leaf, out of reach of most aquatic egg-eaters and under the watchful eye of their father. Its up to him to make sure the growing babies dont dry out and once every minute he splashes them with a swish of his tail. Light bends as it crosses the boundary between air and water and this unwitting physicist adjusts his water jet accordingly, aiming just away from where he sees the eggs to make sure he hits his target. After two days the eggs will hatch, and the fry will drop into the water and swim away.

If theyre unlucky, the new hatchlings might be spotted by a hungry Four-eyed Fish, Anableps . In reality, these hunters only have two eyes, perched high on their head like a frogs, but each is divided horizontally with two separate corneas and pupils. A single lens is flattened, like a human eye, on top and curved underneath, like in most other fishs eyes. With pale, elongated bodies Anableps spend their time lying just below the surface, gazing into two worlds. The lower half of each eye focuses down through the water to watch for other predators, while the upper halves stick out to scan the air and the waters edge for insects, or young tetras, that might fall in and become a meal for Anableps .

These Amazonian oddities are not the only unusual fish, picked from an otherwise monotonous crowd. The worlds waters fresh and salty, shallow and deep are teeming with remarkable species.

In East Africa, in Lake Tanganyika, female cichlids use their mouths as brood chambers. When a pair meets to spawn, the female lays eggs, the male adds his sperm, then the female sucks the whole lot into her mouth where the fertilised eggs will hatch and grow until theyre ready for the outside world. Unless, that is, theres a Cuckoo Catfish nearby. These whiskery, white fish covered in black spots have behaviour just as duplicitous as their feathered namesakes. They swoop in while cichlids are laying eggs and add their own to the mix. Inside the duped females mouth, the catfish hatch and make more space for themselves by eating all the young cichlids.

Further offshore from continental Africa, on the island of Madagascar, in deep, underground caves live gobies, less than a centimetre (half an inch) long, pallid pink and with no eyes. Similar pale, eyeless gobies live nearly 7,000km (4,350 miles) away on the other side of the Indian Ocean, underground in a desert in Western Australia. Recent genetic studies revealed these two groups are closely related; they are evolutionary sisters. For these cave-dwelling fish, long-distance dispersal is really not an option. Theyre confined to their caves and cant risk emerging into daylight; they have no eyes to spot predators and no skin pigments to protect them from ultraviolet rays. The only likely explanation for their disconnected geographies is the movement of continents. A common ancestor to these two groups lived on an ancient, southern supercontinent. Then a split formed between Australia and Madagascar and for the last 100 million years or so the two cave systems, and their divided fish, have been slowly drifting apart.

And in the oceans twilight zone 1,000m (3,300ft) down, where sunshine runs out, live some of the strangest, not to mention the most abundant fish of all. There swim small sharks with glowing spines on their back, probably to warn intruders not to take a bite; others have a pocket on each side of their head that holds glowing slime (and no one really knows why). This is also the territory of bristlemouth fish and lanternfish, sharp-toothed creatures that would fit in the palm of your hand. They illuminate their bellies with blue light and disguise their silhouettes from predators passing below, and some of them talk to each other with coded flashes of light, like fireflies. Deep-sea surveys show these two fish groups reign over the twilight zone. Together there are thought to be hundreds of trillions, maybe even thousands of trillions of bristlemouths and lanternfish alive today, far more than any other vertebrates (followed by 24 billion domestic chickens). Between dusk and dawn, great herds of lanternfish and bristlemouths leave the twilight zone and swim hundreds of metres towards the surface following their food, the wriggling masses of plankton that rise each night. Its the greatest animal migration on the planet and it takes place like clockwork on a daily basis, up and down again, all across the oceans.