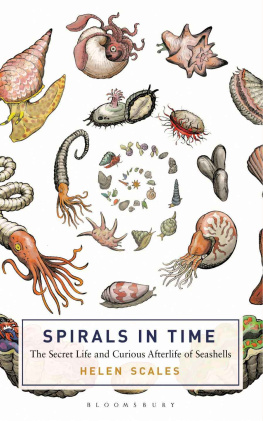

SPIRALS IN TIME

Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

p : The Gene that Cracked the Cancer Code by Sue Armstrong

Atoms under the Floorboards by Chris Woodford

SPIRALS IN TIME

The Secret Life and Curious Afterlife of Seashells

Helen Scales

Bloomsbury Sigma

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

London | New York |

WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2015

Copyright Helen Scales, 2015

Helen Scales has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Photo credits (t = top, b = bottom, l = left, r = right, c = centre)

P. 50 Christian Delbert/Shutterstock. Colour section, P. 1: Alex Mustard/naturepl.com (t); optionm/shutterstock (cr); David Wrobel/Getty Images (br); IDiveDeep/Shutterstock (bl). P. 2: aquapix/Shutterstock (t); Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images (br); orlandin/Shutterstock (bl); Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images (cl). P. 3: Andy Woolmer (tl, tr); Borut Furlan/Getty Images (b). P. 4: All photos by Helen Scales with kind permission of Fatou Janha and the TRY Womens Oyster Association. P. 5: Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Digitised by Smithsonian Libraries, www.biodiversitylibrary.org (tl); Mark Webster/Getty Images (tr); University of Portsmouth (cr); Stuart Westmorland/Getty Images (b). P. 6: Georgette Douwma/naturepl.com (t); HNC Photo/Shutterstock (cr); Alexis Rosenfeld/Science Photo Library (b); D. Parer & E. Parer-Cook/Minden Pictures/Getty Images (cl); P. 7: Helen Scales with kind permission of Archeotur, SantAntioco (tl, tr, cr); Reinhard Dirscherl/Getty Images (b); Courtesy of Archeotur, SantAntioco (cl). P. 8: Laurent Charles, Our Planet Reviewed MNHN-PNI-IRD Expedition (t); Brian J. Skerry/Getty Images (br, bl); Ulf Riebesell, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, Kiel (cr).

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organisation acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN (hardback) 978-1-4729-1136-0

ISBN (trade paperback) 978-1-4729-1670-9

ISBN (paperback) 978-1-4729-1138-4

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-4729-1137-7

For Katie and Ruth

Contents

N ever go anywhere without your seashell. At least that was the rule that Triton lived by. He was a merman top half human, bottom half fish and a demigod in Greek mythology, not a fully fledged deity. Nevertheless, he did his best to dash around playing his trumpet, which was fashioned from a large shell with the end cut off; he used the trumpets ear-splitting roar to scare off raging giants and command the seas. Triton was often outshone by his famous parents Poseidon and Amphitrite, the god and goddess of the sea, not to mention his extended family. Poseidon fathered a prodigious and eclectic assortment of offspring: there was a man-eating cyclops, a sea monster that stirred up island-swallowing whirlpools, a talking stallion, and a sea-nymph who could control violent waves and married a giant with a thousand hands and fifty heads.

Then there was Triton with his shell. His special power was perhaps not as flashy as those of some of his siblings and in-laws, but he was still someone not to mess with. One story tells of Misenus, a mortal from the city of Troy, who thought himself a gifted trumpeter and rashly challenged Triton to a musical contest. Outraged by all the boasting, the demigod shoved Misenus in the sea and drowned him. It seems Triton was a bit sensitive about his seashell trumpet.

Beyond myths and stories, seashells have always been highly valued and revered in the real, human world. Since prehistoric times, we have found shells, picked them up and looked at them in wonder. People have contemplated the seashells beautiful shapes and the mysterious ocean realm they come from, and turned them into great treasures. For centuries, the wail of conch trumpets has echoed across the peaks of the Himalayas, calling Tibetan Buddhist monks to prayer. The conch shells inhabit the Indian Ocean and have been carried hundreds of miles inland, high into the mountains, where they are carved with intricate designs, decorated with jewels and precious metals and adorned with colourful ribbons. Standing on the rooftops of monasteries, monks play shell music into the skies to ward off approaching storms and drive away evil spirits.

Sadly, though, in more recent times, people have begun to lose this sense of awe in seashells. Their magnificence is fading and being replaced instead by inelegant clutter. I brooded on this while hunting around the internet for the words seashell and figurine. A cavalcade of aquatic kitsch unfolded across my screen, and one image in particular stuck in my mind: a little seashell man. His body was a large cowrie shell, his head a slightly smaller one the opening gave him a goofy, crinkled smile and glued on top was a cockleshell hat. His arms and legs were made from four twisted turret shells that poked out at odd angles, and he sat on an elephant made from a dead starfish with one leg raised as a trunk and clam shells for ears (not to worry, though Im sure its what the starfish would have wanted). Another spectacle of shellcraft dreck available to buy at optimistically high prices was a series of ceramic human heads covered in dreadful jumbles of seashells along with strings of pearls, craggy antlers of dead coral and glittering rhinestone seahorses; these unfortunate mannequins looked like mermaids whod fallen into Poseidons treasure chest and come out much the worse for wear.

I encountered yet more seashell trinkets in a rather unexpected place. At Londons Natural History Museum I was invited to go behind the scenes to the basement rooms, where their phenomenal shell collection is kept. They have millions of specimens, catalogued and neatly arranged species by species, but as I walked in the first thing I saw was a glass-fronted cupboard housing a miscellany of altogether more peculiar objects. The curators call this their cabinet of horrors. It contains the various shell paraphernalia theyve been given over the years; some are real shells, others are plastic replicas. Among the gubbins there are ornamental ships with sails made from scallops, and a telephone shaped like a conch shell, taking the phrase a word in your shell-like to its logical conclusion after the Victorians noted that human ears have a spiralling shape similar to shells. Theres a tiny shell-covered piano, and a stack of cowrie shells, each with plastic eyes and a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles that transforms them into studious turtles. Gluing a pair of wobbly eyes on a cowrie is harmless enough, I suppose, but its a far cry from the men and women who buried their dead with shells in a sign of great respect and mourning. Im not saying we should go back to placing shells in graves, but youve got to admit that its funny how things change.

Next page