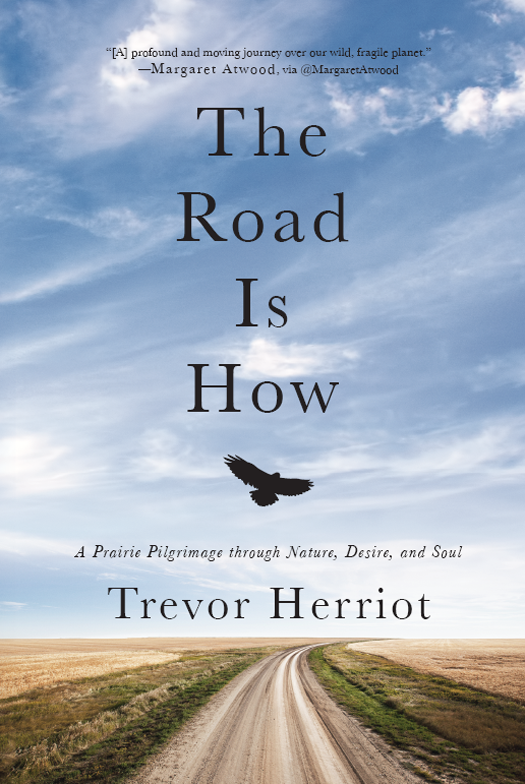

The

Road

Is

How

A Prairie Pilgrimage through Nature, Desire, and Soul

Trevor Herriot

For Olive Jeanne

To compare life to a road can indeed be fruitful in many ways, but we must consider how life is unlike a road. In a physical sense a road is an external actuality, no matter whether anyone is walking on it or not, no matter how the individual travels on itthe road is the road. But in the spiritual sense, the road comes into existence only when we walk on it. That is, the road is how it is walked.

Sren Kierkegaard, Provocations

A YOUNG MAN WALKS FOR A YOUNG MANS REASONS . In the summer of 1691, twenty-three-year-old Henry Kelsey, looking for beaver and friendly Indians who might be persuaded to trap them, left his canoe on the Saskatchewan River and began walking south through muskeg and bog. Within three days, he stepped out of aspen forest and onto the northern edge of the Great Plains. Historians say he was the first European to walk on the Canadian prairie. First to sit with its hunting people, to see its buffalo and grizzly bears, and to ramble through its unploughed world of grass.

Three hundred and some years latergrass ploughed up, buffalo and grizzly goneyoung men go to the mountains to walk. The cultivated plains, the fields and road allowances where GPS-guided machines seed, supplement, and harvest the soil quarter mile by quarter mile, seldom feel the footsteps of any man, young or old. Such a subdued and woebegone landscape will never make the roster of great places to walk. Looking back on it now, the thought that no one walks this land anymore may have been what first made me want to try.

French existentialist and playwright Gabriel Marcel once suggested that instead of Homo sapiens we might call ourselves Homo viator, man the pilgrim, the wayfarer. We are the oddball creatures who will walk two hundred miles along a river to find the headwaters, across a continent to honour a dying friend, or to the sea to scrape salt from the sand and found a nation. Most of us try simpler journeys, but the seeking is the same: a search for heart, a steadfast spirit, peace of mind, a soul worthy of an altar, or an altar worthy of the soul.

We are fond of our big brains but sometimes forget the wayfarer in us whose restless seeking may well have mapped our course as the hominid who wants to know things. Our intricate neural networks may have developed as our ancestors found food and fostered social linkages, but it all started with our feet following ever more complex pathways across the surface of the earth. To remember our wayfaring origins is to wield a metaphysics of hope against the dogma that we are aimless wanderers in a world whose chaotic surface is the sum total of reality. The wayfaring animal suspects there is something else going on and walks with an eye out for signs and symbols. Moving through the ever-patient land, we hope to connect mind to body to earth, begin the descent from outward to inward, and find a way for even our neuroses and distractions to belong. Spiritual writers say that when you take your consciousness down to the territory where your soul waits for you to wake up, it can be like finding a small door in your house you never knew about. You cant open it yourself, but just knowing its there is reassuring, because from the other side comes the scent of a wind that holds everything together in its wide embracethe broken and the whole, shame and forgiveness, despair and gratitude.

In the first days of September, as school and work rang bells to end another summer, I left home and headed east of the city to find that door. Events at the other end of summer had me looking for a better foothold, trying to understand a new feeling of being off balance, of questioning everything I once held as certainty.

There were many questions obsessing me, but none more vexing than the matter of what to do with desire. I used to be happy with the standard explanation: when your eye is drawn by the arc of a womans foot swinging from a sidewalk through a doorway and the pang hits you, its nothing more than hormones, a physical response programmed by selfish genes looking for more opportunities to join in the random sorting out of traits that may or may not be well adapted to the unfolding universe in which they operate. But the more I observe that call and response, the more I wonder. Dismissing the desire inside ussexual and otherwiseas nothing more than biological programming is about as satisfactory as explaining music by referring to sexual and social bonding. I have every respect for evolutionary biology but have trouble seeing Verdi, Mozart, and Chopin as elaborate forms of courtship adaptation, like deer antlers. Never mind music, are we certain we know what antlers are for?

The obsessing over imponderables seemed to start early in the summer when I realized Id become even crankier than usual with my family and the rest of humanity. If you have spent any time defending wild places and animals, you may know what I mean. Helpless to stop it, you watch a favourite stretch of valley vivisectioned by ranchette development, or a wood once filled with warblers and thrushes knocked down to grow soybeans. Each year, more shorelines, pastures, meadows, woodlots, marshes, and hedgerows slide into the jaws of that monstrosity we prefer to think of as the demon spawn of corporate and private greedother peoples, of course, not ours. What is wrong with them? we ask, turning our eyes toward the heavens, or toward Ronald Wright, Jared Diamond, or anyone with an answer. For a time, there is some comfort in that generalizing inquiry, the soothing intellectual grasp on reality that comes from holding on to something as big as a civilization and then pronouncing it innately flawed. But it eventually grows out to a bitterness that wont go away until you grab the other end of the truth and look at the particular by asking instead, What is wrong with me?

I knew I was sunk when I could no longer separate my own motivations from those belonging to the technologists, political leaders, and corporate decision-makers I like to blame. From the right distance, all egocentric, manipulative behaviour begins to look the same, whether you are bulldozing a woodlot or trying to get your wife to make dinner when you think it should be made.

Perhaps worse, for all of my time with birds and the prairie, I was beginning to feel that something was missing in the way I encountered and imagined the other creatures in this windblown land. It was as though my years as the know-it-all naturalist had rendered me deaf to the very spirits that might be able to help me grow up or heal or whatever it is I am supposed to do at this stage of life.

With luck, I might have twenty or thirty years left to find the gentleness and sensitivity that will let me listen more deeply, respond more gracefully. But winter would be here soon. I wanted to go now, to walk out of the city and into the land, following a descent that began three months earlier with a single step off the roof of our house.