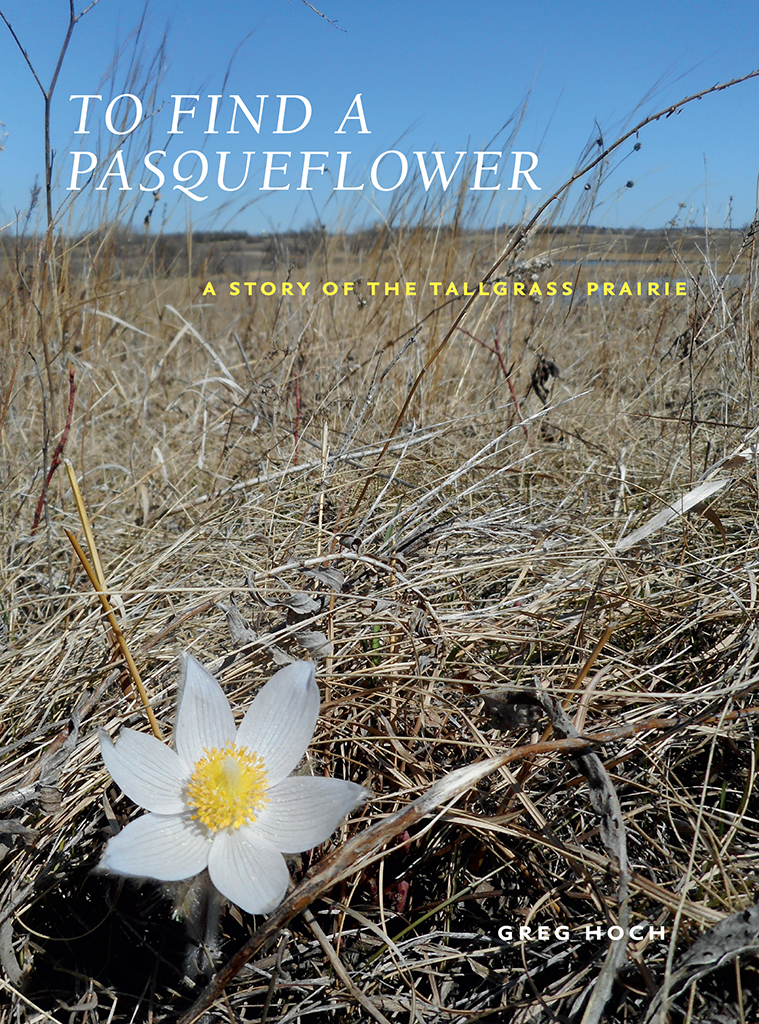

To Find a Pasqueflower

A BUR OAK BOOK

Holly Carver, series editor

TO FIND A PASQUEFLOWER

A STORY OF THE TALLGRASS PRAIRIE

Greg Hoch

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS

IOWA CITY

University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242

Copyright 2022 by the University of Iowa Press

uipress.uiowa.edu

Printed in the United States of America

Design by April Leidig

No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach.

Printed on acid-free paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hoch, Greg, 1971 author.

Title: To Find a Pasqueflower: A Story of the Tallgrass Prairie / by Greg Hoch.

Description: Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2022. | Series: Bur Oak Books | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021032857 (print) | LCCN 2021032858 (ebook) | ISBN 9781609388256 (paperback) | ISBN 9781609388263 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Prairie ecologyGreat Plains. | Prairie ecologyKansas. | PrairiesGreat Plains. | Conservation of natural resourcesGreat Plains.

Classification: LCC QH541.5.P7 C63 2022 (print) | LCC QH541.5.P7 (ebook) | DDC 577.4/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021032857

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021032858

For us of the minority, the opportunity to see geese is more important than television, and the chance to find a pasque-flower is a right as inalienable as free speech.

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

To Pete and To John and Brent

Contents

Acknowledgments

FIRST, I thank Dave for that first visit to Smith Pioneer Cemetery in western Indiana the summer between my freshman and sophomore year. That one trip set my life on a trajectory. And also thanks for the almost daily friendship and mentorship in the three decades since.

This book is the culmination of thousands of conversations with hundreds of people over the last thirty years. Ive tried to capture as much of that as possible. However, there are far too many to try to name individually and not leave just as many out. I thank everyone at Konza Prairiefaculty, post-docs, staff, fellow graduate students, and everyone else. My years there built on and helped refine the interest that developed in Indiana. Next, I thank everyone in the conservation community in Minnesota. Everyone. That includes friends and colleagues at the Department of Natural Resources, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy, The Prairie Enthusiasts, and all the other agencies and organizations that work across Minnesota and across the Midwest to benefit prairies and grasslands.

Earlier versions of several of these chapters appeared in the magazine Upland Almanac.

Last, I thank everyone at the University of Iowa Press who helped make this book possible: Allison, Meredith, Karen, and especially Holly.

Disclaimer

THOSE WHO CLAIM to understand the tallgrass prairie often speak loudly and use strong declarative sentences. Its usually pretty easy to tune them out. There are also those who understand that the prairie is so complex that no one person will ever comprehend all of it or even fully grasp the small segment of the prairie they have spent their life studying, formally or informally. These people speak softly and end many of their comments with question marks. They can be fascinating to converse with. In Coda: Wilderness Letter, one of the foundational essays of the conservation movement, Wallace Stegner (1969) quotes Sherwood Anderson, who wrote about the prairies: I can remember old fellows in my home town speaking freely of an evening on the big empty plains. It had taken the shrillness out of them. They had learned the trick of quiet. The people who best understand the prairie understand quiet and the art of listening.

This book is a summary of my conversations with many people much smarter and more experienced than I, as well as my own education, research, experiences, and observations. It is a reflection of my own interest in and passion for the prairie.

None of the statements that I make in this book is carved in stone and almost everything is debatable. In fact, many of the topics I cover, such as the very nature of what a plant community is, have been vigorously debated for many decades. There are no final answers to these questions or any winners in the debates. I dont ask any reader to agree with everything in this book. I do hope this book sparks thought and discussion. What I am trying to portray is the ever-changing nature of scientific perspective as it studies a dynamic ecosystem, the tallgrass prairie.

I rely heavily on the long-term data set from Konza Prairie in eastern Kansas in this book, simply because it is one of the few long-term prairie data sets out there. Cedar Creek, just south of my current home in Minnesota, is another valuable source of information. Both are founding members of the National Science Foundations Long-Term Ecological Research program. I stand by the validity of my graphs and think I crunched the numbers correctly, but they were designed to be descriptive, not definitive. They would not stand up to the statistical rigor and peer-review process of a research journal. However, that isnt the intent of this book.

The modern Midwest is a human-dominated ecosystem. Humans have largely destroyed or replaced a diverse mix of grasses and wildflowers with monocultures of corn or beans. Even before the plow, humans played a large role in structuring the very nature of the tallgrass prairie.

Over my writing desk at home is a watercolor of prairie-chickens titled Prairie Foghorn by Ross Hier, my friend and favorite artist. Next to that is the following quote from Edward Abbey from his book The Journey Home (1977). Although written about Abbeys southwestern deserts, the idea translates to other ecosystems such as the tallgrass prairie. The moral I labor toward is that a landscape as splendid as that of the Colorado Plateau can best be understood and given human significance by poets who have their feet planted in concreteconcrete dataand by scientists whose heads and hearts have not lost the capacity for wonder. Any good poet in our age at least, must begin with the scientific view of the world; and any scientist worth listening to must be something of a poet, must possess the ability to communicate to the rest of us his sense of love and wonder at what his work discovers. This book is one persons attempt to communicate the science as he understands it as well as his love and wonder for the tallgrass prairie.

Introduction

Grass is the forgiveness of Natureher constant benediction.... Forests decay, harvests perish, flowers vanish, but grass is immortal.Ingalls 1905

You must not be in the prairie; but the prairie must be in you. That alone will do as qualification for a biographer of the prairie.... He who tells the prairie mystery must wear the prairie in his heart.Quayle 1905

Prairie, to most Americans, is a flat place once dotted with covered wagons.Leopold 1942a

Newcomers to the prairie are at first disconcerted by its nakedness. Later they will wish it were not so private.