Acknowledgments

The editors are grateful for the support that they have received in completing this project. We thank Martin Melosi and Joel Tarr, both for their editorship of this series, the History of the Urban Environment, and for their leadership in founding and strengthening the field of urban environmental history. We also benefited from the guidance of Sandy Crooms at the University of Pittsburgh Press. We appreciate the efforts of the editorial and design staff at the press as well as the insights offered by the anonymous peer reviewers.

The American Society for Environmental History and its former executive director, Lisa Mighetto, generously offered us meeting space during the 2017 conference in Chicago, allowing us to workshop the individual papers and engage in meaningful collaboration with our contributors; we are grateful. During this same conference, the Newberry Library hosted an open session exploring environmentalism and environmental justice in Chicago; we thank the Library and the noncontributor participants, Jerry Adelmann and Kim Wasserman. We also appreciate our collaborators for their innovative, deeply researched essays and their efforts to meet various deadlines.

We are grateful to the editor and publishers of the Journal of Historical Geography for allowing us to include a revised version of Craig E. Coltens article, Chicagos Waste Lands: Refuse Disposal and Urban Growth, 18401990, from its 1994 issue. We also share our appreciation of the editor and publisher of Environmental Justice for permission to add a revised version of Sylvia Hood Washingtons article, Mrs. Block Beautiful: African American Women and the Birth of the Urban Conservation Movement, Chicago, Illinois, 19171954, from its 2008 issue. Our collection of essays is all the stronger for the participation of these noted scholars.

We also want to thank our colleagues at North Central College and the University of Oklahoma. We are indebted to the Faculty Developmentand Research Committee at North Central College and the provost, vice president of Research, and History Department at the University of Oklahoma for their financial assistance in publishing this volume. We thank Curt Foxley for the index.

Finally, we want to celebrate our families and friends for their unwavering support and enthusiasm for our efforts.

INTRODUCTION

WILLIAM C. BARNETT

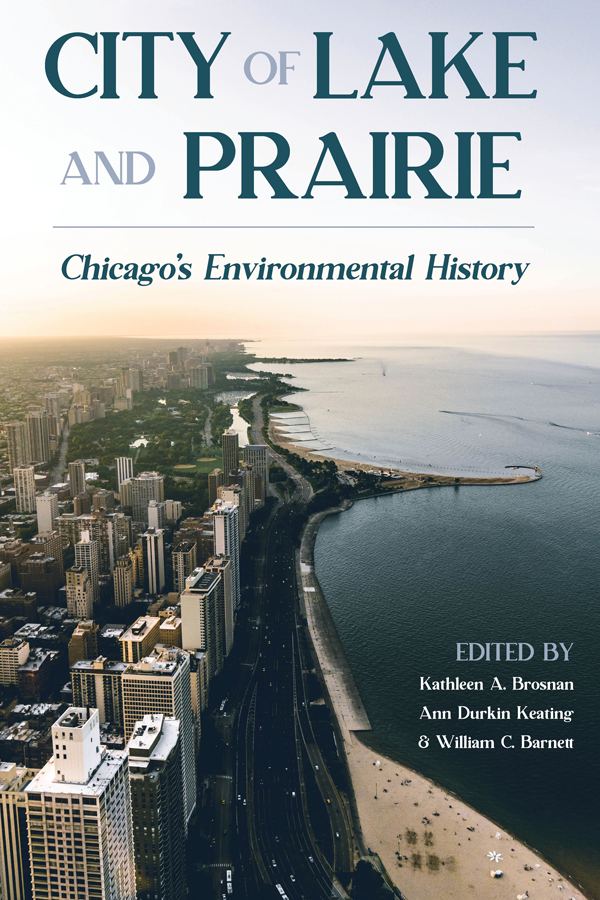

Humans have been altering the natural world of prairies and wetlands along Lake Michigan ever since they first built communities here. From the opening chapter on native peoples expanding the tallgrass prairie to the closing chapter on twenty-first century efforts to restore the damaged Calumet ecosystem, this volume provides rich stories of people transforming this region. Many of these groups believed they were improving their community and its use of nature, even as they reversed their predecessors efforts. First, native peoples expanded the tallgrass prairies, then early farmers plowed up those prairie lands, and later industrialists and suburban developers built where farms once stood. Assertions that these transformations represented progress, however, have been called into question in recent decades because of increased understanding of ecology and, later, of growing awareness of environmental justice, sustainability, and climate change. This trio of emerging concepts points the way to new types of human transformations that can improve built environments and restore natural landscapes by balancing economic prosperity with the health of ecosystems and human communities. People will continue to remake Chicago, but this constant process of urban transformation can yield healthier environmental relationships. To achieve this goal, it is critical to examine the history of the intricate and constantly evolving system of man-made and natural components thatpeople have woven together to build the city of Chicago on this dramatically altered landscape of lake and prairie.

Chicago residents and visitors to the city each have their own unique understanding and personal map of the complex web of interconnected neighborhoods along the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan. And all of these maps are in motion, as Chicago is in an ongoing process of transformation and reinvention, one that is surpassed by few American cities. Longtime residents have multiple layers to their understanding of Chicagos urban geography, with memories of the built environments of their early years lying beneath a contemporary map that accounts for urban redevelopment. Historians and geographers possess an ability to dig deeper into the citys past, researching and writing about the ways that previous generations reshaped the urban environment, and revealing broad patterns such as industrial booms, transportation shifts, or one immigrant group replacing another. Chicago has been reconfigured by American migrants moving west, by ongoing waves of European immigrants, by African Americans migrating from the rural South to the urban North, and by more recent newcomers from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Each group fought to make a place for itself, providing labor and ideas to fuel the citys economy, creating new communities and businesses, and reshaping neighborhoods. Todays Chicago is the result of the struggles and contributions of countless men and women, and the citys environmental history is a complex story of a landscape transformed by its people.

Visitors and newcomers to Chicago soon become familiar with a few neighborhoods, but most have difficulty creating their own maps that reflect the complexity of this sprawling city. Outsiders typically start not with a micro-level understanding that emerges from childhood, but instead with a macro-level perspective that is less detailed but can show how Chicago differs from other cities. For the first-time visitor flying into OHare or Midway airports, the view from an airplane window is arrestingthe topography is as flat as a table, with a cluster of skyscrapers rising from the lakeshore, and development radiating across the landscape. Especially at night, with the lake in darkness and streets lit up, the traveler looks down on a built environment that appears to be a perfect Cartesian grid, with straight lines extending north, south, and west, as regular as graph paper. Immigrant communities cannot be identified, and lines drawn onto the landscape by ethnicity, religion, class, and race are not visible. This flat plane can be viewed as a blank slate, a vast canvas on which to plan, build, and then rebuild a city. In the nineteenth century boosters such as land speculator Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard and first Chicago mayor William Butler Ogden inscribed canals, railroads,and industrial facilities onto the prairies and wetlands, and twentieth-century city planners and political leaders such as the architect Daniel Burnham and Mayors Richard J. and Richard M. Daley sketched out new visions for the booming metropolitan region. For better and for worse, a myriad other Chicagoans have also left their marks on the constantly evolving urban landscape.