NATURES

METROPOLIS

Chicago and the Great West

WILLIAM CRONON

WWNORTON & COMPANY

New York London

Praise for Natures Metropolis

Natures Metropolis is that rare historical work which treats nature and the moral force we derive from it seriously.... The roots of the modern environmental predicament are plainly visible in the economic dynamism that brought about the rise of Chicago in the mid-nineteenth century, which is a captivating story in its own right.

Verlyn Klinkenborg, The New Yorker

William Cronon challenges many of the conventions of both urban and western history in this pathbreaking book, and does so with unusual intelligence and elegance. More important, he helps lay the groundwork for a vital new field of scholarship: the history of the natural environment and its relationship to human society.

Alan Brinkley, Columbia University

No one has ever written a better book about a city.... No one has written about Chicago with more power, clarity and intelligence than Cronon.... Natures Metropolis is elegant testimony to the proposition that economic, urban, environmental and business history can be as graceful, powerful and fascinating as a novel.

Kenneth T. Jackson, Boston Globe

Natures Metropolis is economics, history, life, business, and national destiny, so brilliantly mingled and united that is is hard to tell what is economics and what is life, where business stops and ecology or national destiny takes over. That is, of course, the way things are; but it takes a master historian-writer to create a tableau so vividly alive, so marvelously interesting.

Robert L. Heilbroner

Tallgrass prairie. Courtesy University of WisconsinMadison, Arboretum.

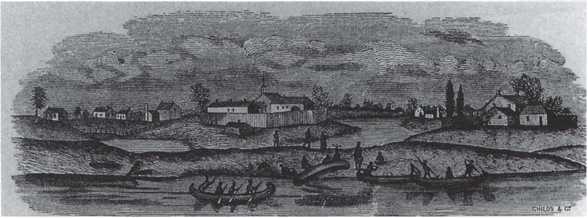

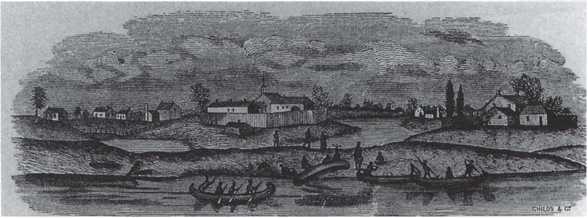

Henry Rowe Schoolcrafts view of Chicago in 1820. The sandbar at the mouth of the river is in the foreground, and Fort Dearborn is on the left bank. The site of the building on the right had been a fur-trading center since the 1770s. Reproduced from Chicago Magazine (1857), authors collection.

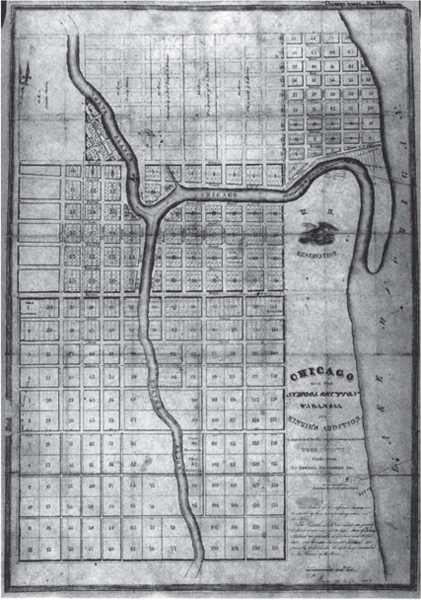

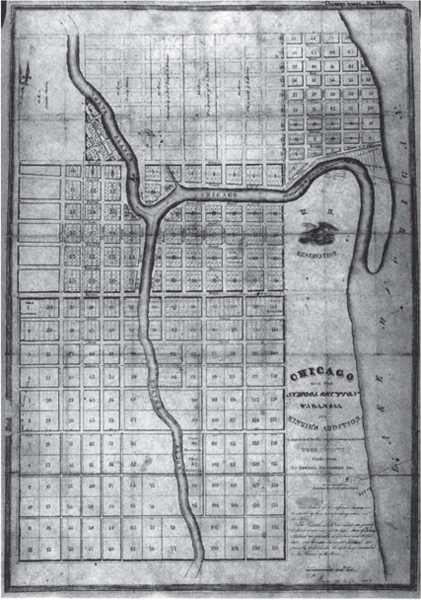

Joshua Hathaways plat map of Chicago in 1834. Despite the urban appearance of this map, most of this land was as yet unoccupied. Note the two branches of the Chicago River, the site of Fort Dearborn, and the sandbar that still blocked the rivers mouth. Courtesy Chicago Historical Society.

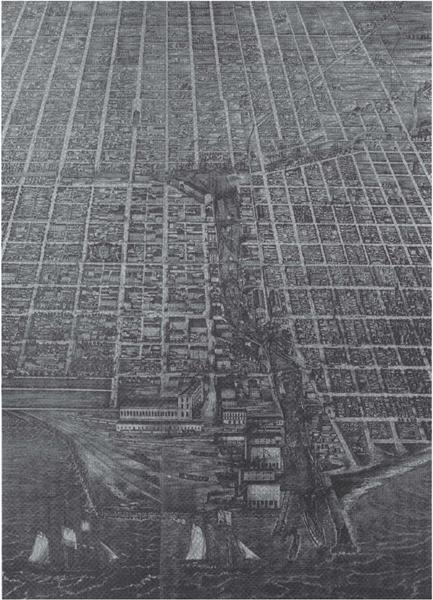

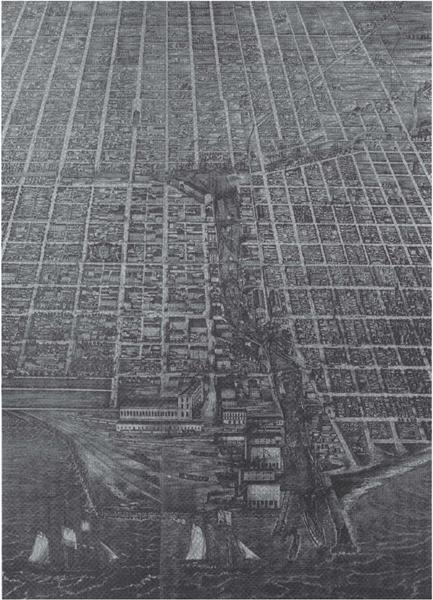

James Palmatarys birds-eye view of Chicago in 1857. This detail from the famous birds-eye shows the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad, in the left foreground, leading to two large grain elevators at the mouth of the Chicago River. Ships line the main branch of the river, loading and unloading in the warehouse and business district, which is clearly visible as the line of larger buildings on the south bank. Courtesy Chicago Historical Society.

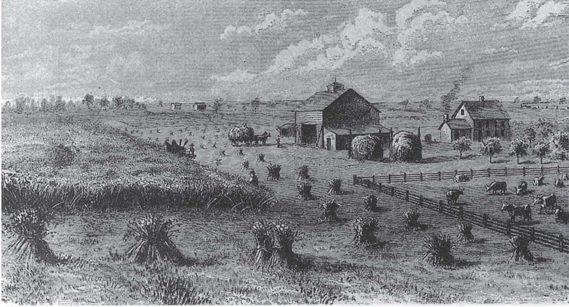

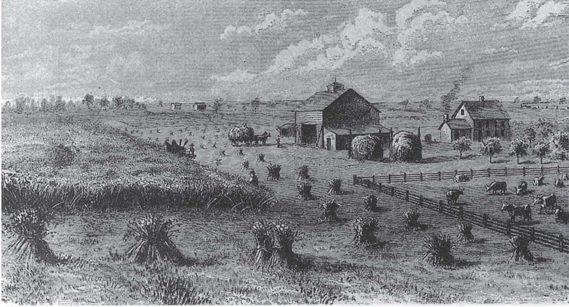

A one-family Dakota wheat farm in the 1880s. A farmer is at work on a reaping machine at the edge of the uncut grain, and carefully gathered piles of wheat sit drying in the field. Grazing animals in the pasture to the right are prevented from eating the cash crop by a wooden post-and-rail fence. Note the train on the right horizona familiar icon of the transportation revolution that had helped call this scene into being. Reproduced from William M. Thayer, Marvels of the New West (1887), authors collection.

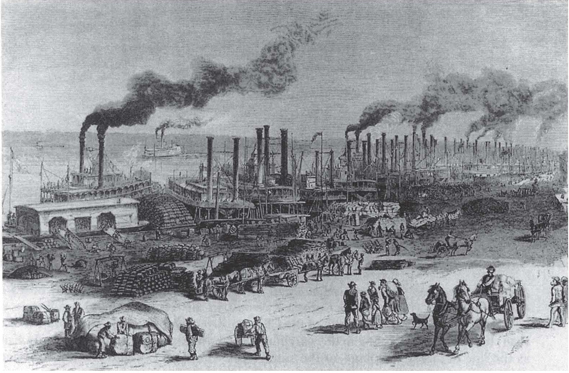

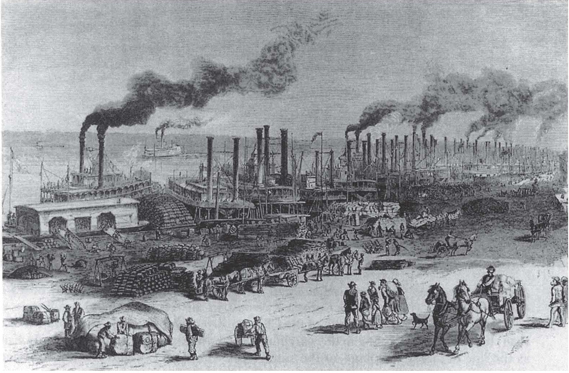

The St. Louis levee in the heyday of water transportation. Dozens of steamboats line the riverbank, and the shore is abustle with activity as laborers and merchants move goods from one place to another. Note the sacks of grain that have been taken from the flatboat at the left and are about to be loadedall by handonto the steamboat behind. Reproduced from Harpers Weekly, October 14, 1871, courtesy Yale University Library.

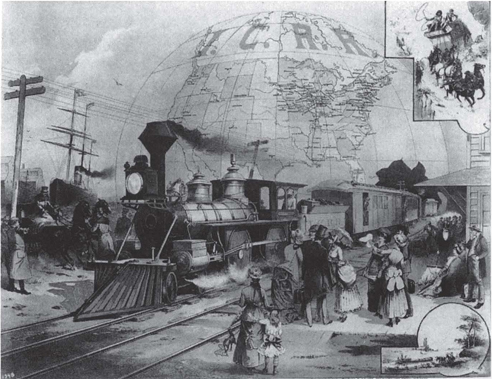

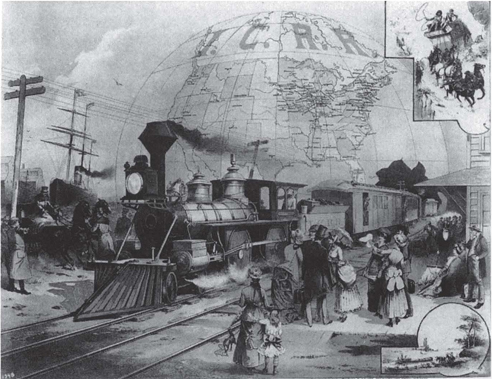

The Worlds Railroad Scene. When the Illinois Central Railroad sought to convey a sense of its own importance with this 1882 lithograph, it superimposed its routes on a globe-scale map of the United States. In the foreground, wondering observers watch as a train leaves the station. Note the telegraph lines, steamship, and grain elevator at left, and the inset images of old-fashioned road and water transportation in the upper right and lower right. Courtesy Library of Congress.

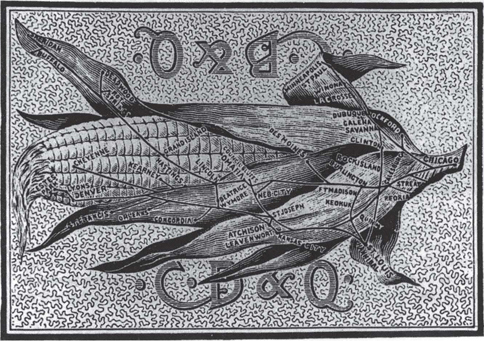

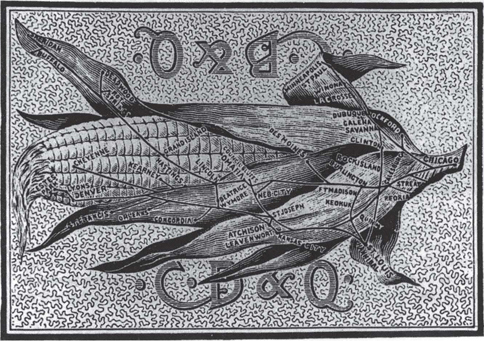

The Great West as Chicagos corncob. In 1891, the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad distributed a deck of playing cards to favored customers, backed with this imagewhich speaks for itselfl Reproduced from authors collection.

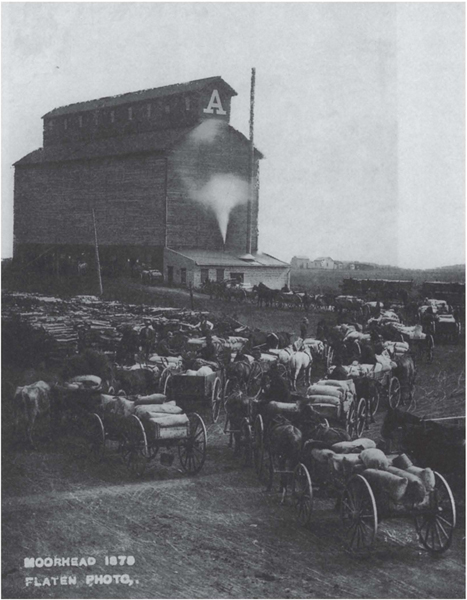

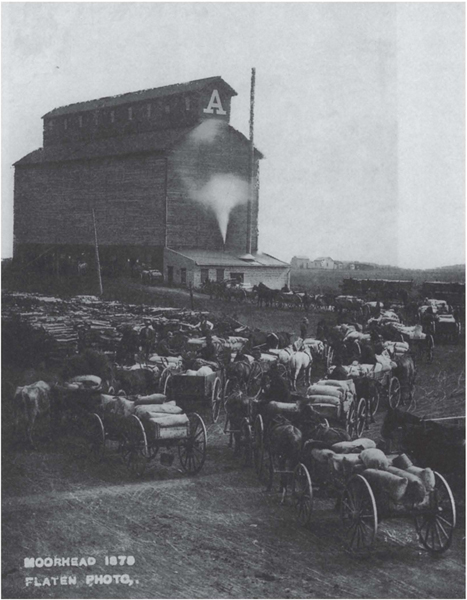

Wheat arriving at a Moorhead, Minnesota, elevator in 1879. Farmers brought their crops to country elevators like this one in wagons filled with burlap sacks. For grain to move through the elevator and into waiting railroad cars, its owners had to pour it from the sacks and mix it in common bins, an act that had far-reaching implications for the agricultural economy. Note the large heap of fuelwood in the left foreground to power the elevators steam engine. Courtesy Clay County Historical Society, Moorhead, Minnesota.

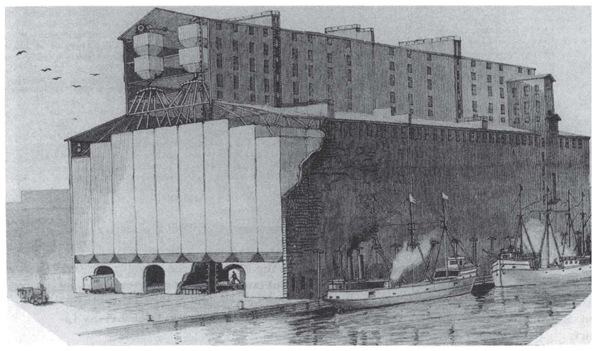

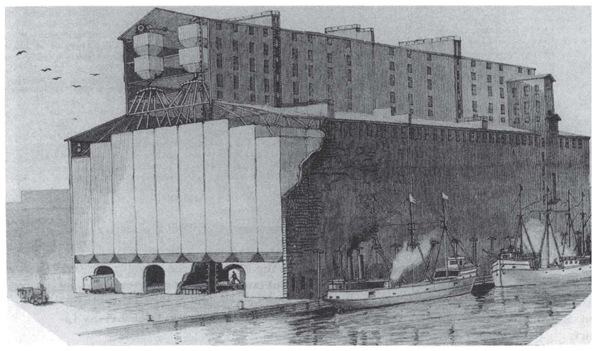

Cutaway diagram of Chicagos Armour Elevator A and B in 1891. Grain was transported to the top of the elevator in buckets attached to an endless belt. There it was weighed in a pair of hoppers before falling down one of several chutes into a bin specially designated for its grade. It was finally carried by gravity to the holds of lake vessels waiting on the Chicago River. Reproduced from Scientific American, October 24, 1891, courtesy Yale University Library.

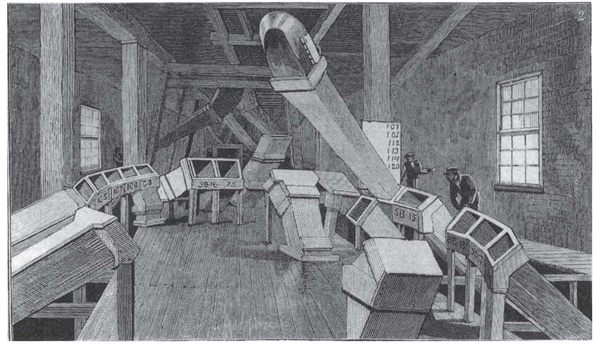

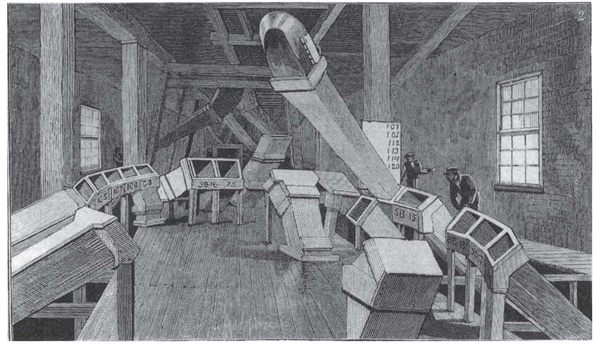

Detail of the chute sorting mechanism atop Armour Elevator A and B. Each bin in the elevator corresponded to a particular grade of grain. The rotating chute from the weighing hopper allowed workers to send grain into the appropriate bin. Shippers got receipts that entitled them to withdraw from the elevator an equal quantity of the same grade of grain they had put inbut they could not get back their own r-rain. Reproduced from

Next page