Contents

Guide

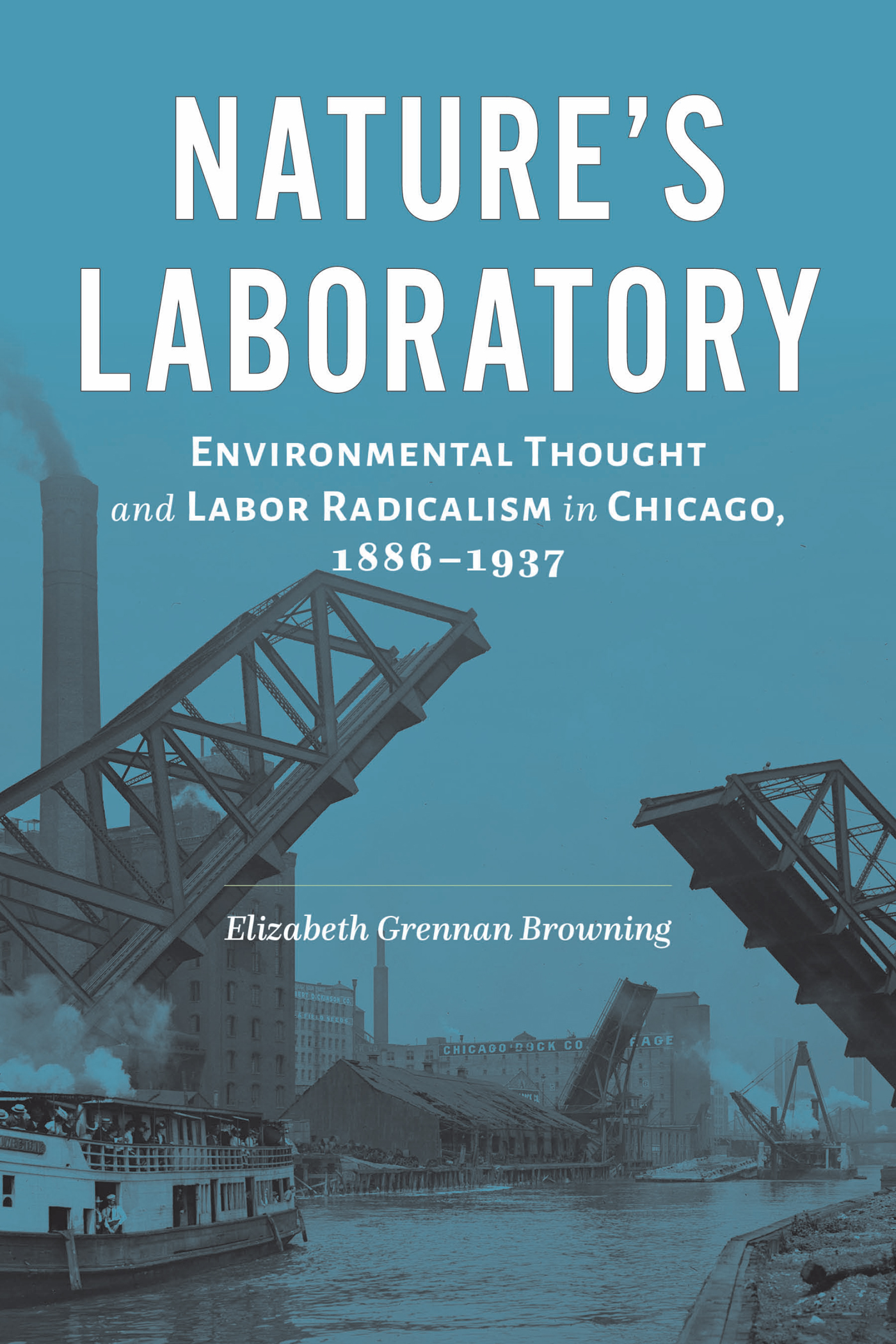

Natures Laboratory

Natures Laboratory

Environmental Thought and Labor Radicalism in Chicago, 18861937

Elizabeth Grennan Browning

Johns Hopkins University Press

Baltimore

2022 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4214-4521-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4214-4522-9 (ebook)

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Chicago has always signified a larger-than-life aura within my orbit of life. That the Windy City encompassed many diverse and complex worlds was one of my earliest understandings of American urban landscapes and ultimately led me down a path of exploring urban environmental history. The story goes that when my mother was growing up on the South Side, my grandmother recommended that she read Herbert Asburys Gem of the Prairie: An Informal History of the Chicago Underworld to better understand the citys history. My grandmother worked at a number of administrative posts across the city, including at the Chicago Stockyards and the Chicago Board of Trade. My grandfather worked for the Chicago Park District, spending much of his time maintaining Marquette Park. Never having had the opportunity to meet them, I often contemplate what rich stories about Chicago they would have shared with me. As I reflect on the many individuals who have made my journey in writing this book possible, I am indebted to these two and to my mothers storytelling for making clear to me what a remarkable place the City of Lake and Prairie is.

This book has taken shape throughout my time within a number of remarkable communities of historical scholarship. At the University of California, Davis, Louis Warren, Ari Kelman, Diana Davis, and Lisa Materson guided my research and exemplified what brilliant historical scholarship, writing, and teaching entail. I am beyond grateful for their wisdom, mentorship, generosity, kindness, and friendship over the years. In my time at UC Davis, this book project benefited from conversations with James Housefield, Sally McKee, Ian Campbell, Jonathan London, Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, Kathryn Olmsted, Lorena Oropeza, Eric Rauchway, Rachel St John, Julie Sze, Alan Taylor, Cecilia Tsu, Clarence Walker, and Mike Ziser. My thanks also go to Carrie Alexander, Rebecca Egli, Ross Eikenbary, Nancy Gallman, Daniel Goldstein, Beth Hopkins, Griselda Jarquin, Javiiicob Lee, Jessica Mayhew, Molly McCarthy, Nancy McTygue, Antonia Mehnert, Sophie Moore, Loren Michael Mortimer, Nicole Naar, Tom ODonnell, Nick Perrone, Stacy Roberts, Jordan Scavo, Jennifer Sedell, Nari Senanayake, Beth Slutsky, Tuyen Tran, Grace Woods, and those who participated in the Mellon Environments and Societies colloquium series. I am particularly grateful for the brilliance, thoughtfulness, and good humor of Shelley Brooks, Lindsay Chervinsky, Cori Knudten, and Mary E. Mendoza.

This project would not have been possible without the generous support of the UC Davis Department of History, including the Reed Smith Dissertation Year Fellowship, and grants from the UC Davis Environments and Societies Mellon Research Initiative, Russell J. and Dorothy S. Bilinski Educational Foundation, UC Davis Institute for Social Sciences, UC Davis Graduate Studies, and Phi Beta Kappa Northern California Association.

The Newberry Library was a wonderful home for my Chicago-based research. A National Endowment for the Humanities seminar, Making Modernism, provided the opportunity for early archival explorations that significantly shaped the direction of the book project. Liesl Olson helped me build a foundation for understanding the richness and complexity of Chicago history and was a phenomenal mentor throughout the seminar and beyond. Thanks also to Paul Durica, Jacqueline Goldsby, Neil Harris, Bill Savage, Carl S. Smith, and Timothy Spears. I had the opportunity to return to the Newberry with a short-term fellowship sponsored by the Society of Mayflower Descendants in the State of Illinois. Brad Hunt generously introduced me to many Chicago scholars and shared his expertise on the citys history. I am grateful to Erik Gellman, Rima Lunin Schultz, Elizabeth Tandy Shermer, Ellen Skerrett, and Katherine Turk for welcoming me and sharing resources that led to new research trajectories for my project. The staff of the Newberry went above and beyond to assist my research. I owe special thanks to Martha Briggs, Kristin Emery, Patrick Morris, Matthew Rutherford, and Jessica Weller. The University of Chicagos Robert L. Platzman Memorial Fellowship gave me the wonderful opportunity to delve into the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Centers wealth of Chicago resources and benefit from the staffs expertise. Special thanks to Daniel Meyer and Diana Rose Harper. At the Hull-House Museum, Lisa Junkin Lopez offered research advice and insight about the field of public history. I thank the archivists, librarians, and curators at the Art Institute of Chicagos Ryerson and Burnham Archives, the Chicago History Museum, the Harvard Business School Baker Library (special thanks to Melissa Murphy), the Harvard Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, the ixUniversity of Illinois at Chicago Special Collections Department, and the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature.

My research benefited from the insights of scholars who commented on my work at conferences for the American Society for Environmental History, the Modern Language Association, and the Urban History Association. I especially thank Carl Abbott for directing me to many important sources. Thanks also to Florence Boos, Allen Dieterich-Ward, Andrew Hurley, Benjamin Heber Johnson, Samuel Kling, Eleanor Mahoney, Jason Martinek, Timothy Neary, Garrett Nelson, and Jon Teaford. Wendy Pollack helped inspire me on my path toward becoming a historian through our work at the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law. My thanks also to Jon Garthoff and Mark Sheldon for helping me find my way to environmental history.

In my four years of postdoctoral research at Indiana Universitys Environmental Resilience Institute (ERI), the Indiana UniversityBloomington Department of History, and the Integrated Program in the Environment (IPE), I have gained a deep appreciation for the importance of environmental history in cross-disciplinary efforts to address global societys most pressing socioenvironmental problems. My time within the ERI community has forever shaped my vision of environmental historians role within public deliberations about environmental change. Eric Sandweiss was tremendously kind in introducing me to countless fascinating Indiana environmental histories and sharing his expertise in urbanism, cultural landscape studies, and public history. The ERI fellows introduced me to the joys of interdisciplinary scholarship on environmental resilience and provided new insights on the history of ecologyI cant thank them enough for their camaraderie: Jason Bertram, Lingxi Chenyang, Adam Fudickar, Matt Houser, Alex Jahn, Ranjan Muthukrishnan, Tara Smiley, Abigail Sullivan, Pascal Title, Luis Inaraja Vera, and Maria Whiteman. ERI has become an important voice in the field of environmental resilience and implementation science on account of the remarkable leadership provided by Eva Allen, Gabe Filippelli, Ellen Ketterson, Janet McCabe, Sarah Mincey, David Polly, and Jim Shanahan. At ERI I was fortunate to also learn from the expertise of Shahzeen Attari, Angela Babb, John Baeten, Ana Bento, Eduardo Brondizio, Analena Bruce, Suzannah Evans Comfort, James Farmer, Rob Fishman, Beth Gazley, Nathan Geiger, Stacey Giroux, Michael Hamburger, Sarah Hatcher, Rachel Irvine, Jason Kelly, Ben Kravitz, Liz Kryder-Reid, Jen Lau, Rebecca Lave, Jay Lennon, Kirstin Maxwell, Kirstin Milks, Kim Novick, Heather Reynolds, Byron Santangelo, Adam Scribner, Matt Sieber, Marta Venier, and Landon Yoder. Abby Henkel, Jonathan Hines, Joe Lange, Julie McLenachen, Yoanna Sayili, and Vanessa Worthy have my sincere thanks for always knowing the answers. Betsy Stirratt, Linda Tien, and their phenomenal team at the Grunwald Gallery braved the rails of the Monon in what were some of the most enjoyable months in my time at IU. I am grateful for the generous support of Indiana Universitys Prepared for Environmental Change Grand Challenge. At the Indiana UniversityBloomington Department of History, my thanks for insightful questions and insights from Judith Allen, Keith Barton, Jim Capshew, Kalani Craig, Nick Cullather, Konstantin Dierks, Colin Elliott, Anne Gray Fischer, Wendy Gamber, Janine Giordano Drake, Sara Gregg, Peter Guardino, Carl Ipsen, Ben Irvin, Tina Irvine, Sarah Knott, Lara Kriegel, Scott Libson, Ed Linenthal, Pedro Machado, Jim Madison, Michael McGerr, Michelle Moyd, David Nichols, Scott OBryan, Robert Pergher, Nick Roberts, Julia Roos, Tatiana Saburova, Jonathan Schlesinger, Leah Shopkow, Rebecca Spang, David Thelen, Carl Weinberg, and Ellen Wu. Sarah Mincey has been incredibly generous in welcoming me into the world of IPE and has inspired me with her tireless efforts to promote interdisciplinary research and prepare the next generation of leaders in environmental resilience. To the educators and staff of the Campus Children Center, thank you for all of your support and care throughout my familys time in Bloomington.