ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER R. BROWNING

R EMEMBERING S URVIVAL

INSIDE A NAZI SLAVE-LABOR CAMP

CHRISTOPHER R. BROWNING

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2010 by Christopher R. Browning

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Browning, Christopher R.

Remembering survival: inside a Nazi slave-labor camp/

Christopher R. Browning.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07019-4

1. World War, 19391945Concentration campsPolandStarachowice.

2. Forced laborPolandStarachowiceHistory20th century.

3. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)PolandStarachowice. 4. JewsPoland StarachowiceHistory20th century. 5. NazisPolandStarachowice History20th century. 6. Wierzbnik (Starachowice, Poland)History 20th century. 7. Starachowice (Poland)History20th century. 8. Holocaust survivors PolandStarachowiceBiography. 9. Wierzbnik (Starachowice, Poland)Biography.

10. Starachowice (Poland)Biography. I. Title.

D805.P7B76 2010

940.53'1853845dc22

2009034202

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

F OR J ENNI

CONTENTS

PART I

T HE J EWS OF W IERZBNIK

PART II

T HE D ESTRUCTION OF THE W IERZBNIK G HETTO

PART III

T ERROR AND TYPHUS: F ALL 1942 S PRING 1943

PART IV

S TABILIZATION

PART V

C ONSOLIDATION , E SCAPE , E VACUATION

PART VI

A FTERMATH

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Illustrations follow chapter 17.

MAPS

O CCUPIED P OLAND , 19391944

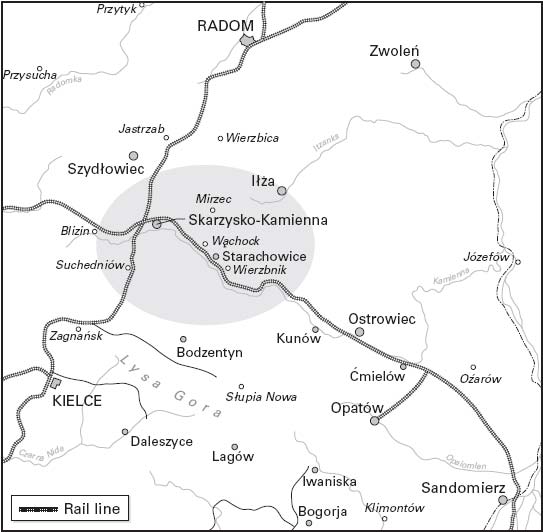

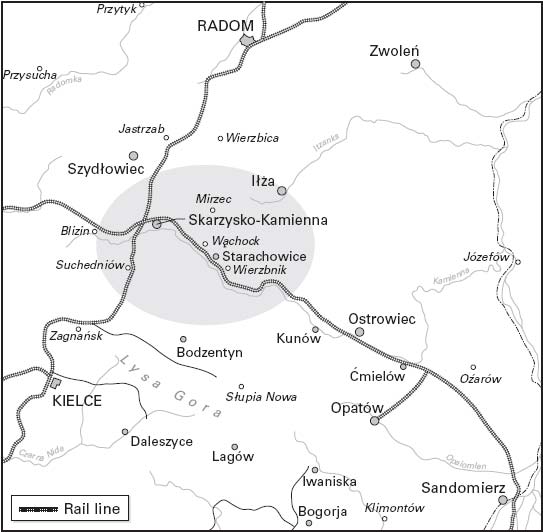

W EIRZBNIK -S TARACHOWICE : T HE S URROUNDING R EGION

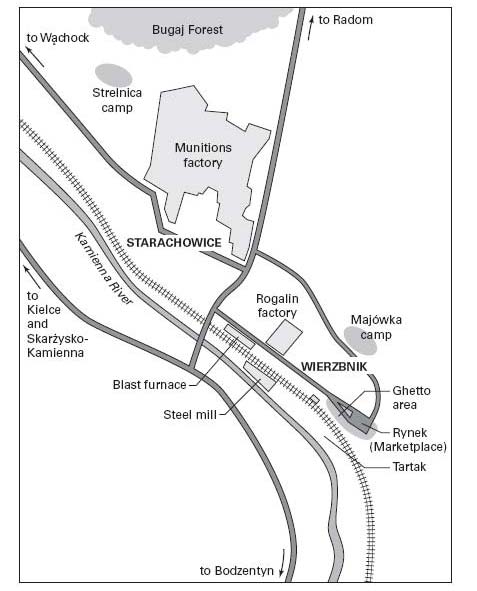

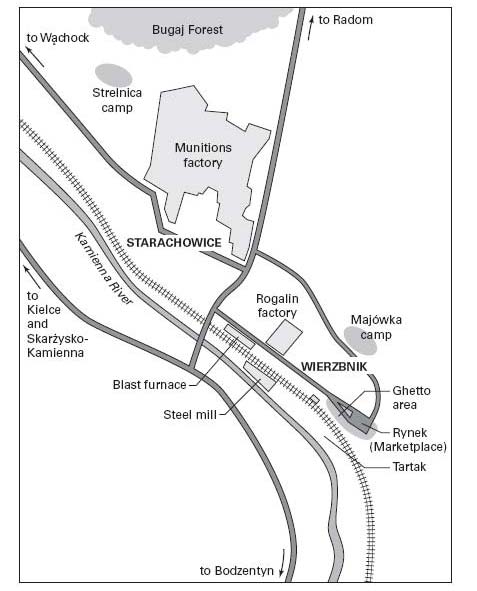

W EIRZBNIK -S TARACHOWICE : G HETTO , F ACTORIES, AND C AMPS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book could not have been written without the assistance and support of many people. First of all, I am indebted to the staffs of many archives, who helped in assembling and providing access to the sources on which this study is based: the Central Agency for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes in Ludwigsburg, Germany; the Visual History Archive of the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation Institute; the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Yad Vashem; the Fortunoff Archive in the Sterling Library at Yale University; the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City; the National Archives, Washington, DC; the Holocaust Survivor Oral Testimonies collection of the University of MichiganDearborn, the Bundesarchiv Berlin, and the Starachowice branch of the Archivum Pa nstwowe w Kielcach. The Visual History Archive was exceptionally helpful in providing early access to its collection of videotaped testimonies, and Yaacov Lozo wick at the Yad Vashem Archives patiently answered many requests for copies of materials.

nstwowe w Kielcach. The Visual History Archive was exceptionally helpful in providing early access to its collection of videotaped testimonies, and Yaacov Lozo wick at the Yad Vashem Archives patiently answered many requests for copies of materials.

Numerous individuals provided me with important sources. Rachell Eisenberg sent me a copy of her sister Goldie Kalibs memoirs, and Phillip Eisenberg shared with me a copy of his fathers account. Tova Pagi sent me a copy of her childhood memoirs, and Silvio Gryc sent me the relevant translated chapter from the Moskowicz memoirs.

Some of the sources were available only in languages I do not read. These were made accessible to me by indispensable translations from Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew by Ella Benson, Sylvia Noll, Barbara Kalabinski, Andrew Kos, and Nadav Davidai.

Indispensable financial support and release time for research and writing was provided to me as an Ina Levine Invited Scholar at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in 20023 and a fellow of the National Humanities Center in 20067. Both the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the USHMM and the National Humanities Center offer ideal environments for scholarship, and my year at each will always remain a cherished memory. My earlier academic home, Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington, provided the initial help in developing this topic, and the Institute for Arts and Humanities at my current academic home, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, allowed me to keep the momentum going at a crucial juncture.

The intellectual stimulus and support of colleagues is of course one of the great joys of the profession, and I have received much from many. In particular, Frank Bialystok, Nechama Tec, Sidney Bolkovsky, Douglas Greenberg, Sarah Bender, and Dick de Mildt have provided very important concrete assistance as well. Patrick Montague and Anita and Maciej Franciewicz made my visit to Wierzbnik-Starachowice both a memorable and a fruitful experience. Two of my graduate students, Michael Meng and Eric Steinhart, took time off from their own research to make archival forays on my behalf and procure vital documentation at key moments. Ewa Wymark has been generous in sharing various leads she has uncovered in her own research.

Above all, I am grateful to the fifteen survivors of the Starachowice factory slave-labor camps who agreed to meet with me and provided many hours of interviews, and especially to Howard Chandler, who helped arrange many of these interviews. As will be evident to an attentive reader of the footnotes, the magnitude of my debt to these interviewees is incalculable. Over the course of my research, I had assembled the written, transcribed, and/or taped accounts of 292 different survivor witnesses, and I initially conceived of these interviews as a useful supplement. In the course of my writing, however, it soon became apparent that their importance to my project was exponentially greater than I had originally expected, and the book would have been greatly impoverished without them. Given that different people experience the same events from different vantage points and remember the same events in different ways, the accounts of multiple witnesses invariably differ in both minor and major ways. Thus I fear that each of my invaluable interviewees will be somewhat disappointed when I have not accepted everything as they remember it. I hope for their understanding and remain deeply in their debt.

A NOTE ON NAMES

Dilemmas and choices abound concerning the use and spelling of names in this book. The first was which name to use in which circumstance, because many survivors went by different names in the period before 1945 and then subsequently in their new countries. In Israel and North America, where most of the survivors settled, their names were routinely hebraicized or anglicized. In the footnotes, I have used the names current at the time the testimonies were given, for this is how the testimonies are identified in the archival collections or court records. In some cases, the same person gave two different testimonies and listed his or her name somewhat differently each time, such as Abraham in one and Avraham in the other, or Najman in one and Naiman in the other.

nstwowe w Kielcach. The Visual History Archive was exceptionally helpful in providing early access to its collection of videotaped testimonies, and Yaacov Lozo wick at the Yad Vashem Archives patiently answered many requests for copies of materials.

nstwowe w Kielcach. The Visual History Archive was exceptionally helpful in providing early access to its collection of videotaped testimonies, and Yaacov Lozo wick at the Yad Vashem Archives patiently answered many requests for copies of materials.