Contents

Guide

Narratives of Annihilation, Confinement, and Survival

Culture & Conflict

Edited by

Isabel Capeloa Gil, Catherine Nesci and

Paulo de Medeiros

Editorial Board

Arjun Appadurai Claudia Benthien Elisabeth Bronfen Joyce Goggin Bishnupriya Ghosh Lawrence Grossberg Andreas Huyssen Ansgar Nnning Naomi Segal Mrcio Seligmann-Silva Antnio Sousa Ribeiro Roberto Vecchi Samuel Weber Liliane Weissberg Christoph Wulf Longxi Zhang

Volume 79

ISBN 978-3-11-062824-1

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063113-5

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063098-5

ISSN 2194-7104

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019931984

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

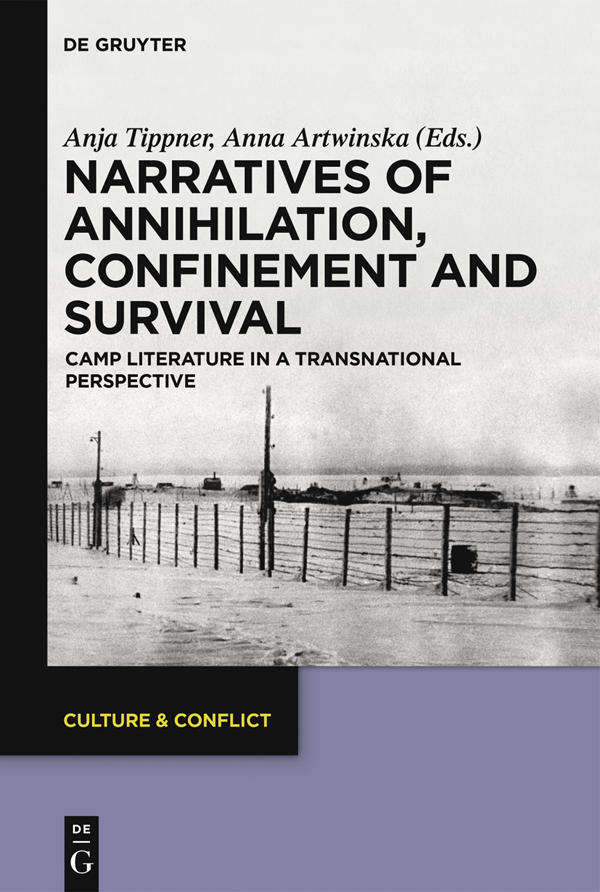

Cover image: Gulag Vorkuta, 1946. Sputnik / akg-image

www.degruyter.com

Anja Tippner and Anna Artwiska

Introduction: Camp Narratives in a Comparative Transnational Perspective

The English historian Eric Hobsbawm coined the phrase age of extremes to describe the twentieth century. In his opinion, the years between 1914 and 1989 were marked by terrible catastrophes, man-made disasters, wars, and genocidal atrocities in an unprecedented way that called for new forms of documentation, representation, and cultural remembrance. The post-war cultural history of many European countries, and especially the period since 1989, can be understood as an intellectual and emotional struggle with the traumatic events of the Second World War, the Holocaust, Hiroshima, and the Gulag, as well as other effects of totalitarian rule. Historian Hayden White characterized the two world wars, the Holocaust, and Stalinism as modernist events, that is as events that cannot be

forgotten and put out of mind or, conversely, adequately remembered, which is to say, clearly and unambiguously identified as to their meaning and contextualized in the group memory in such a way as to reduce the shadow they cast over the groups capacities to go into its present and envision a future free of their debilitating effects.

(

The complicated and sometimes contradictory process of remembering these events often centers around accounts of camp experiences, since these occupy a singular place among the atrocities defining this century.

At this point in history, we are in possession of a vast archive of texts that deal with the effects of political violence and camp experiences in the twentieth century and that are devoted to conceptualizing the experiences of camp survivors. For a long time, literary criticism has largely focused on testimonial and fictional accounts of the Holocaust and Nazi concentration camps, and less on camp narratives that deal with Soviet and other socialist camps. The primacy of Holocaust camp narratives is understandable, given the importance of the Holocaust for the development of a transnational European memory. However, its predominance belies the fact that socialist labor and penal camps were transnational sites of terror in their own right and have also become transnational lieux de mmoire . After a period that was dominated mainly by acts of witnessing and This volume intends to fill this gap by providing a theoretical frame as well as an overview of several important European camp literatures and, last but not least, case studies of iconic camp narratives.

The concept of camp narratives rather than Holocaust narratives or Gulag narratives is based on the assumption that despite their obvious political and ideological differences, literary accounts of camp experiences share common traits, aesthetically as well as thematically. This book presents readings of camp literature that deal with extreme experiences, thus underscoring the similarity between the literature of Soviet Gulag, the literature of the Holocaust, and literature about other camp and prison experiences. As some of the contributors to this volume have noted, these similarities have not been lost on the survivors themselves. In many ways, literature about Nazi concentration camps serves as a point of reference for camp narratives in the same way that the Holocaust serves as a point of reference for other genocidal actions: The emergence of Holocaust memory on a global scale has contributed to the articulation of other histories. Ultimately, memory is not a zero-sum game. ( they are predominantly judged by these poetics.

One of the goals of this volume is to point out the ways comparison is used in depicting camp experiences and how the similarities between different types , Matt F. Oja urged us to view camp experiences in a broader perspective:

What we really need to define is not camp literature, but the camp experience. []. The definition must surely be universally applicable. [] this experience need not literally involve a camp of the Stalinist or Nazi model; it may be set in a prison, a bamboo cage, the basement of city hall, or anywhere else.

(: 273)

The question of comparison is a difficult albeit a necessary one. As Neil Levi and Michael Rothberg lucidly observed in their discussion of the uniqueness of the Holocaust and the Nazi camp system, there is a need to compare in order to fully fathom the depth of a historical event (Levi and Rothberg 2003: 441442). We understand comparisons in this way, namely as a tool enabling us to put historical experiences into perspective. In doing so, we also acknowledge the assessments and insights of survivors and witnesses, such as Primo Levi, Margarethe Buber-Neumann, and Julius Margolin, who were comparing both types of camps in the first place. Thus, comparison here is not meant to parallelize different camps and the systems that produced them, ) Comparing thus is not a form of equalizing the political systems that established the camps, but rather sheds light on the similarities as well as differences in experiencing these camps.

A reference point for the comparative analysis of camp literature delivered here can be found in comparative genocide studies, which make extensive comparisons between different catastrophes, using the Holocaust as a paradigm in a non-competitive comparative history (: 380)

***

This volume presents essays on camp narratives by international scholars. It deals with camp narratives that relate to different types of totalitarian experience in Europe. The overall aim is to identify patterns in camp writing. In various ways, the essays in this volume discuss how to think about camp experiences and what representations of the camps look like within different national literatures in Europe. This approach is, by necessity, comparative, in as much as it is concerned with specific cases and their historical, political, and aesthetic contexts. The essays look for common patterns of camp writing regardless of the political circumstances that produced them. order to show the ubiquity of the topic as well as the transmission of forms. Looking at different texts from a variety of literatures, however, patterns emerge in the representation of camp experiences. It is surely no coincidence that almost all contributors refer to the seminal texts by Primo Levi, Varlam Shalamov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and Imre Kertsz in order to conceptualize camp experiences. To a greater extent than critics thus far have realized, these texts are cross-referenced among different camp narratives.