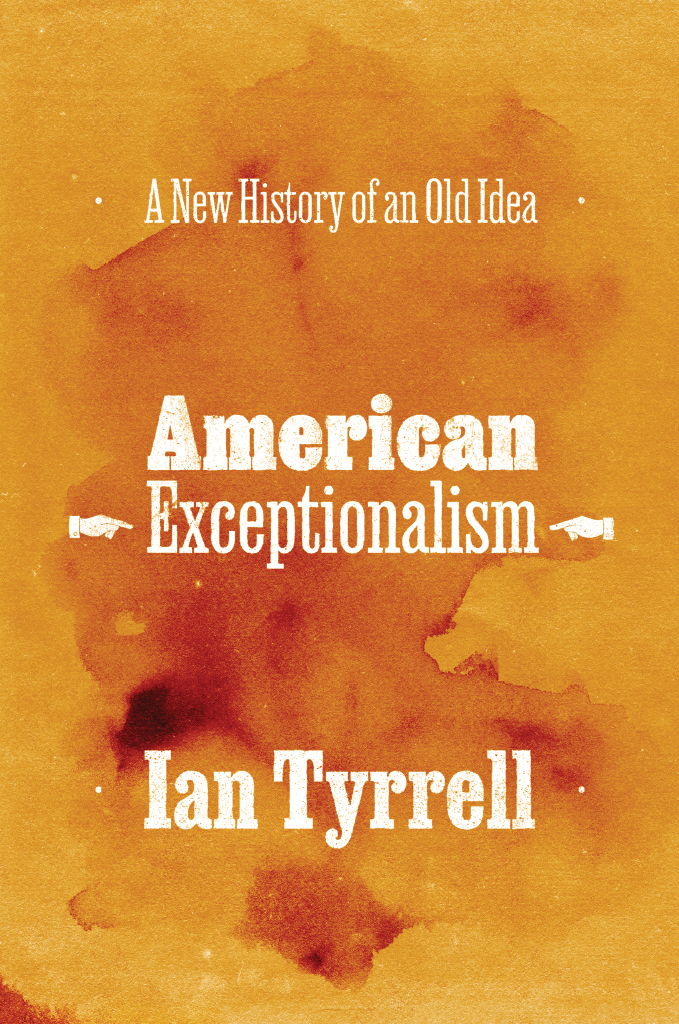

American Exceptionalism

American Exceptionalism

A New History of an Old Idea

IAN TYRRELL

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-81209-0 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-81212-0 (e-book)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226812120.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tyrrell, Ian, author.

Title: American exceptionalism : a new history of an old idea / Ian Tyrrell.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021010982 | ISBN 9780226812090 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226812120 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : ExceptionalismUnited States. | United StatesHistoriography. | United StatesHistoryPhilosophy.

Classification: LCC E 169.1 . T 97 2021 | DDC 973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021010982

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Diane Olive Collins, 19482021

Writer, educator, and so much more

Contents

The Peculiar Tale of American Exceptionalism

American exceptionalism has had a strange history. Little known in public debate as late as 2007, the term exceptionalism proliferated in usage after Barack Obamas election as U.S. president. When Republicans denounced Obama as an enemy of American Exceptionalism, television viewers scurried to their computers and smartphones to find out from the World Wide Web exactly what this obscure term meant. A graph of its usage in the American media shows it soaring from practically nothing in 2007 to a peak in 201112. In the 2012 presidential election, American Exceptionalism became for the first time an entire chapter in the platform of an American political organization, the Republican Party.

The real spark was a Barack Obama news conference in 2009. On his first trip abroad as president, he averred in Istanbul that the United States, especially in foreign policy, had like every other nation made mistakes and exhibited flaws, all admissions that raised American eyebrows. Then, in Strasbourg, France, Obama had the effrontery, in some eyes, to relativize American power and its mission in the world.

Republicans seized on Obamas words to condemn him, and that attack set the stage for the frontal assault on his presidency that culminated in the 2012 election. Ironically, a fuller reading of his Strasbourg conference showed that Obama did subscribe to American exceptionalism. Exceptionalism had morphed into an ideology reflecting and shaping a social and political worldview, and through which public policy would be refracted.

As with many terms and concepts, the election of Donald J. Trump as president in 2016 gave this American exceptionalism a strange turn, with a swag of articles declaring its end or its decline, or its souring, as David Frum wrote in the Atlantic.

Though Trump had borrowed (unacknowledged) the Make America Great Again slogan from the successful 1980 presidential run of Ronald Reagan, it was clear that for Trump, great again meant something other than a singular status in the world. Great did not mean exceptional; it had connotations of scalegreat, greater, greatestor of a numerical grid, whether measured by the size of navies, armaments, gross domestic product, or any other aspect of quantitative national attainment. It did not mean a nation set in a separate category, with unique moral and political ideals. Trump never favored the city upon a hill concept of the United States as a model for the world, as Ronald Reagan did and as Barack Obama concurred. If greatness were to be meaningful as exceptionalism, it must be as a true greatness distinguished by its values from mere quantitative superiority.

The difference between great and exceptional is foundational to the discussion in this book because greatness has a habit of altering over time. The United States is undoubtedly a great power, possibly the greatest yet in world history. But with China challenging American economic hegemony, and many conventional standards of exceptionalism in material life erodedin educational achievement, equality of opportunity, economic growth, and governmental conductsomething other than greatness would be needed to back the exceptionality of the United States. More important, the idea of American exceptionalism posits the United States as exceptional from the start, at a time and in an imperial world when it clearly was not great as a military or economic power.

American exceptionalism seems to many U.S. historians to be a settled question. Some never did support the theory, others no longer do. The rest, perhaps still a majority, probably support it only in carefully qualified and limited intellectual contexts. But Im inclined to think that the skeptics underestimate the resilience and the cultural sway of this concept for the American people. In other words, a gap remains between historical interpretation on the meaning of U.S. history on this issue and the wider publics conflation of patriotism with exceptionalism. It is this idea of American exceptionalism as a discursive practice that concerns me in this book. Just because something cannot be verified as fact or seems old-fashioned as an idea in cutting-edge scholarship doesnt mean its hold is diminished. American exceptionalism is especially important as a contested idea in the current political conjuncture, but I suspect that it will continue to be important for quite some time.

The kerfuffle over the ideological doctrine of exceptionalism during the Obama presidency generated much heat but little enlightenment. Yet the character of the debate did show two distinguishing marks: first, that the widespread and often belligerent use of American Exceptionalism as an ideological ism has been a recent phenomenon; and second, that the idea behind the term was shaped by political forces and subject to conflicting interpretation and shifting meanings. In this book, I capitalize Exceptionalism in the term only in reference to its current ideological and political iteration. Otherwise, I use American exceptionalism to refer to the more general and underlying set of ideas prominent in American society and politics long before the term itself came into being. American exceptionalism as a clearly articulated concept and term dates only from 1929, but it has since the beginning of the twenty-first century been used to describe an idealized version of the American past. But the internal coherence of that belief and its changing valence over time require close inspection.

The idea of the United States as exceptional can be easily found in the early republic, though the term was not invented then. Other formulations were used, such as the model republic or experiment. Applied mostly to the prosperity, wealth, or liberal institutions of the nation, the closest was the old and now unfamiliar English word

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).