Conor Mihell is an award-winning environmental and adventure travel journalist based in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. He is a frequent contributor to explore , Cottage Life , and the Globe and Mail , and is currently an editor-at-large with Canoe & Kayak magazine. He is also a long-time sea-kayak and canoe guide on Lake Superior and its inflowing rivers, and an instructor of outdoor adventure leadership for regional outfitters and at Sault College of Applied Arts and Technology. Mihell grew up on Lake Superiors north shore. His family heritage in the region dates back nearly two hundred years and includes a Lake Superior lighthouse keeper, postmaster, and Sault Ste. Marie town clerk. The Greatest Lake is his first book. Visit his website at www.conormihell.com .

Acknowledgements

The best thing about fully immersing yourself in an area are the relationships that come with it. For the past ten years, Ive made Lake Superiors north shore my home. Its wild shores, tributary rivers, watershed lakes, and coastal communities are where I endeavour to spend as much time as possible. In my infatuation with this place, Ive got to know some wonderful people. My wife Kim and I met while working together as guides at Naturally Superior Adventures on the shore of Michipicoten Bay. In the ensuing years, Kim has joined me on countless adventures and has always provided loving support for my lifestyle as a vagrant writer.

Also in Michipicoten, my stalwart friend David Wells has offered me years of encouragement, employment, and a place to sleep, eat, and paddle the most important things I know. In the final days of preparing my manuscript, he offered me a desk in his cabin, a small log structure perched on greenstone bedrock with a wall of windows overlooking the lake. It is the most inspiring view in the world.

Thanks to my parents, who shared with me a passion for the creative arts, a sense of curiosity, and always encouraged me to follow my heart. My stepmother, artist Sandra Hodge, kindly volunteered to provide an illustrated map for this book.

Countless friends up and down the north shore have offered me much over the years: Mike and Colleen Petzold of Caribou Expeditions in Goulais River, my surf bud Ray Boucher in Wawa, guiding mentor Tarmo Poldmaa, staunch environmentalists and backcountry skiers Robin MacIntyre and Enn Poldmaa in the Bellevue Valley, Kenny and Shirley Mills in Michipicoten Harbour, and Bruce Lash in Sault Ste. Marie. Master craftsman Torfinn Hansen and his partner, Mary Jo Cullen, were always generous with availing their wonderful cottage whenever I needed a place for an extended stay. Thanks also to Jorma Paloniemi and his partner, Lorraine Wakely, for sharing their tireless and collective sense of all-season adventure.

A few of the stories in this volume were offshoots of work I did for several magazines and newspapers. Tim Shuff, the former editor of Adventure Kayak magazine, made great contributions to my early development as a writer and has become a great friend. I have always enjoyed working with Victoria Foote at ON Nature magazine. Jeff Moags sharp editing with Canoe & Kayak magazine helped me win a Northern Lights Award for travel journalism. Thanks also to Martin Zibauer and Michelle Kelly at Cottage Life for entertaining my ideas from Ontarios frontier. Similarly, Darren and Michelle McChristie have always provided space for my work in producing Superior Outdoors magazine from their home in Thunder Bay. Barry Penhale and Jane Gibson, founders of Natural Heritage Books (an imprint of Dundurn), responded to my proposal for a book project with immediate support.

Thanks also to the Ontario Arts Council for financial support through its Writers Reserve program.

Finally, thanks to all those who stand up for Lake Superior and realize that the joys of its rugged beauty, wild mystique, and sweet-tasting water are both endless and fragile.

Afterword

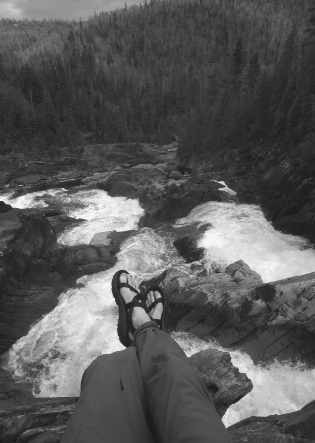

Almost a decade has passed since the late May evening when my friend David Wells and I sat on the sweeping sand and gravel beach facing Lake Superior at the mouth of the Dog River, thirty kilometres west of Wawa, and wondered what this place would be like in fifty years. Would it be covered in Club Medtype hotels and swarming with tourists? Might we be watching the trickling outflow of a massive hydroelectric dam, its turbines whirring under the force of Denison Falls, the 150-foot cataract just upstream? Or could it be developed for cottages, with personal watercrafts and powerboats buzzing offshore? The best option we could come up with is that the place would be deserted, like it was on that spring day.

Im happy to report that the better part of a decade into our thought experiment, Dog River remains much the same. Spring still arrives with the contours of the beach reshaped by autumn gales and winter ice; you can still scoop drinking water right off the beach; and, if you tune your entire body just right, you can still feel the earth-shaking power of Denison Falls upstream. In fact, Im even happier to say that there are good odds the place will remain the same for another generation to enjoy because it is now protected by a provincial park.

Meanwhile, back down the coast in Michipicoten, talk of a proposed aggregate quarry that wouldve blasted shoreline rock and shattered Wellss outfitting business and ecotourism lodge has been silenced by a global economic crisis and, perhaps, the undercurrents of a newfound awareness of the intrinsic role Lake Superior plays in northeastern Ontarios economy and psyche. Its telling that in the summer of 2011, over a quarter of the population of job-strapped Wawa some five hundred residents signed a petition against a multi-year plan to study area bedrock as a deep repository for spent nuclear fuel bundles. Even if the waste dump never came to fruition, the studies alone wouldve injected millions of dollars into the local economy. But many locals wanted none of it. At the top of their reasons for opposing the idea were concerns over the threat of radiation escaping from the so-called deep geological vaults and contaminating the big Great Lake on Wawas doorstep.

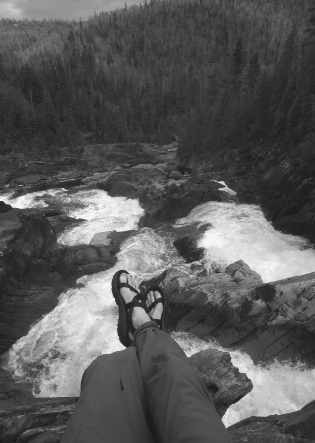

The view from the top of Denison Falls on the Dog River. This remote, fifty-metre-tall waterfall located a few kilometres inland from Lake Superior was a favourite of Bill Mason, a famous Canadian canoeist, filmmaker, artist, and author. Masons efforts to raise awareness of Canadas endangered rivers saved many wild waterways from the threat of hydroelectric development. Though its contained within a provincial waterway park, Denison Falls is still listed as a potential source of thirty-five-and-a-half megawatts of hydroelectricity by the Ontario Power Authority.

There are similar tide shifts up and down the shore. In Marathon, citizens have rallied behind developing a new platinum, copper, and nickel mine with an environmental conscience; Terrace Bay has, for the most part, cleaned up the awful legacy of Kimberly Clarks pulp mill and embraced the image of a clean Lake Superior as a town motto, with two Slate Island woodland caribou emblazoned on its town coat of arms; and down the road in Rossport, Nipigon, and Red Rock, Parks Canadas recently formed Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area is being heralded as a tourism-based initiative that balances economic benefits with the permanent protection of the regions natural heritage.

Of course, there are always threats. The impacts of climate change are being manifested on Lake Superiors water column and coastline with alarming alacrity. As water temperatures have increased, corresponding changes have been observed in the lakeshores unique communities of vegetation wispy and cactus-like glacial throwbacks that have persisted since the last ice age due to the lakes perennially cool waters. But Lake Superior isnt so cold anymore. Botanists are now witnessing these species demise, as well as the die-off of a unique subspecies of white birch tree that grows old and tall in the wet, fog-drenched hills surrounding Lake Superior.