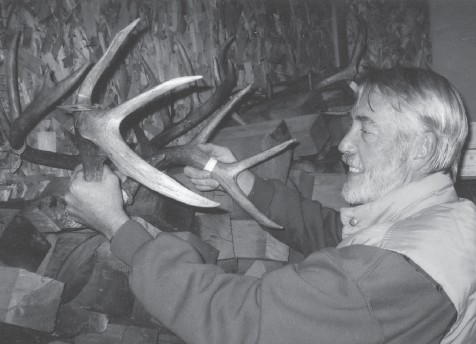

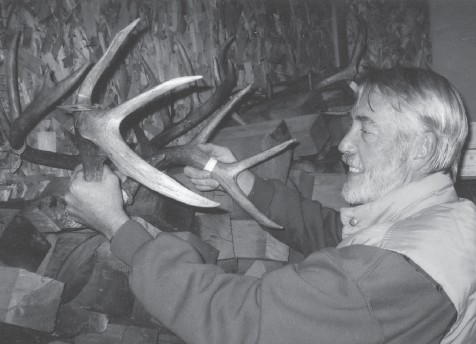

This book combines my own experience as a deer hunter with the expertise of many people who know a lot more than I do about much of what youll read here. These people include old friends plus several new acquaintances that I probably never would have known had they not willingly shared time and stories with me. Some of them volunteered as photographers too, and in several cases where we took pictures of each other doing things with deer, I used the best pictures of me, and the worst ones of them. Joe Siperek welcomed me into his professional venison-processing operation, explained everything, and photographed me performing the five steps of skinning a deer. Thats where I was when country neighbor Chris Young brought in the buck that appears on page . Similarly, Len Nagel, taxidermist and proprietor of the Antler Barn (an incredible collection of two thousand sets of antlers), enlightened me on the expanding antler market and guided me through the intricacies of deer taxidermy. Nagels wife, Barbara, kindly posed for the camera in her deer hide car coat and sent food home with me. Evelyn Maryanski of Blue Mountain Taxidermy let me photograph her caping a huge buck and helped me better understand the skills underlying her art. Betsi Hook jumped enthusiastically into the gory abyss to demonstrate the gutting of a deer for my camera. Dave Savko, who has forgotten more about venison cooking than I can claim to have ever known, contributed not just recipes but provided insights that influenced this book and the way I now cook venison.

Without the thoughtful and cooperative assistance of certain hunting partners, past and presentespecially my son Nathan, also Bill Sheesley, Skip Sheesley, Steve Hook, Ted Wilson, and several others, who each were deputized at various moments to either stand still and be photographed or do the photography (Um, move a little to the left...)I wouldnt have been able to illustrate this book with the authentic actions of real deer hunters.

After the Hunt: What Now?

BEYOND THE KILL

The deer has fallen. That is the point at which this book begins. After the killing shot is fired, the echoes and images of that brief, violent moment quickly drift away, carrying with them the fatigue from the long hours of careful stalking and patient waiting. Silence fills the air. The hunt is over. The whitetail buck lies crumpled upon the earth, its mute form a testimony to the finality of the ultimate act of hunting. We are both elated and sad.

There is a philosophic conflict in our mixed emotions. Abiding by the standards of the sporting ethic, we agree that the act of killing to acquire a game animal is only one of the many reasons for engaging in the sport of hunting in this modern age. Yet, for how long would we continue to hunt if that one reason, the kill, were to be repeatedly denied us through poor luck and circumstance? One year? Ten years? A lifetime? The answer is personal, of course. We should each ask ourselves just how important the kill really is, for in our answer will be a measure of our commitment to the sporting aspect of hunting. If we must always succeed in killing something, then we have failed in our sport.

Unlike small game hunting, in which an empty bag is of no more economic consequence than the cost of a pound or two of meat, deer hunting provides the possibility of a grand prize for success. Frankly, a whitetail deer is worth a lot of money. The value of a deer is roughly equivalent to the cost of a decent deer rifle or shotgun and a pocketful of ammunition. Add a second deer and you can then cover the cost of boots, hunting clothes, a knife, and maybe even a tankful of gas. But, if we continue to think in these mercenary terms, as though deer hunting were a business enterprise, we will quickly lose our enjoyment of hunting. If we instead consider the value of a fallen deer from the point of view of a wise consumer, we can actually increase our overall appreciation of hunting. Particularly if we do our own butchering, preserving, tanning, and handicrafts, using with the skills of our own hands the carcass of a fallen deer, we can further justify our desire to succeed in dropping a deer because we will have extended the sport beyond the kill itself. And, in the future, our enjoyment of the sport will not culminate and then fade at the moment of the kill. If we are able to realize that within us is a responsibility to use a deer to the fullest advantage and value, we will have enhanced not only the worth of a deer, but our own worth as well.

The author is a meat-hunter, but he has a sincere respect for trophy hunters.

THE WHITETAIL DEER: A RENEWABLE RESOURCE

The whitetail deer is definitely not on the endangered species list. Far from it, in fact. The whitetail is so ecologically adaptable that the real problem is keeping deer populations down within controllable limits. We think of deer as creatures of the forest, and they are, but it is more accurate to think of deer as dwellers on the edges of the forest. Large tracts of mature woodlands offer very sparse food supplies to deer, whereas the bushy, brushy low growth of edge-type cover provides a cornucopia of foods that deer can easily obtain. Ironically, it was the white mans axe and the spread of civilization across America that improved, rather than destroyed, the whitetail habitat. As the land was settled and the forests were cleared to provide acreage for crops and farms, more edge cover was created and the deer population began to grow.

The whitetail deer became a major source of protein for the new and growing cities, serving as a temporary substitute for domesticated farm animals while American agriculture of the 19th century evolved from subsistence farming into more efficient and productive operations capable of feeding a growing nation. However, this uncontrolled market hunting eventually offset the original increase in the deer population that had begun over a century earlier. Finally, between 1890 and 1920, most states enacted laws to protect the whitetail deer, and it was during this same time that scientific principles of game management were first applied. Today, the various state game and conservation agencies can predict within a few percentage points what the annual harvest will be, and they have the necessary tools to help make these predictions come true, such as doe permit systems, the setting of seasons, and game law enforcement. Scientific management of deer herd size is directed towards achieving stable, rather than just large, populations of whitetails. As a rule of thumb, the optimum deer population that can be maintained per square mile of deer habitat is about twenty deer. Too many deer can deplete the supply of browse faster than it can recover through natural growth. A smaller, well-fed deer herd can easily survive a harsh winter, but an overcrowded and undernourished deer herd faces the gruesome prospect of wholesale death from disease and starvation.

Hunting is the only means we have for preventing catastrophic swings in the deer population from too high to too low. Ironically, without hunting, the whitetail deer species conceivably could become endangered in localized areas. In the absence of natural predators (chiefly the cougar and the wolf) and without the culling of the herd as was done by the Indians, there have been no other feasible means of controlling deer populations other than by hunting. The recent emergence of the coyote in the midwestern and northeastern USA might alter that dynamicbut the outcome has not yet been projected.