Also by Paula Young Lee:

Deer Hunting in Paris: A Memoir of God, Guns, and Game Meat

Game: A Global History

Gorgeous Beasts: Animal Bodies in Historical Perspective

Meat, Modernity, and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse

Copyright 2014 by Paula Young Lee

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-661-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62914-999-8

Printed in the United States of America

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

Is venison safe to eat? Why does it taste gamy? What can be done to make venison better? For as long as humans have been eating venison, which is a very long time indeed, these questions have been asked and answered in a bewildering number of ways. There are a few reasons why the answers are so inconsistent, but it starts with the fact that people havent always been talking about the same thing.

Prior to the Industrial Age, venison referred to the meat of any traditional game animals taken by hunting. In Europe and England, traditional game animals were chiefly members of the Cervidae familya group that still includes deer but also elk, caribou, moose, and reindeeras well as bears and wild pigs. The term venison existed in opposition to cattle, which referred to livestock mammals in general, like cows, sheep, goats, and pigs. In other words, venison did not necessarily come from a deer, moose, or any other cervid. To be venison, it had to meet two criteria. 1) It had to come from a traditional game animal living in the wild, and 2) it had to have been taken by hunting and not by snaring, trapping, or some other means.

Todays consumers prefer not to think about the animals life or the means of its taking. Instead, the animal has one name, and its meat has another. So, cows become beef, calves become veal, pigs become pork, sheep become mutton, and deer become venison. It makes no sense to say that pork comes from a cow. Or that mutton comes from a pig. There is a logic to the pattern, and that logic affirms: if X animal, then Y meat. If deer, then venison. The deer no longer has to be wild, and it does not have to be hunted, for its meat to be called venison.

There are two kinds of (deer) venison: venison that is wild, and venison that is farmed. The farmed kind, which is sold in stores, is becoming more widely available to middle class consumers. The wild version is now generally lower in culinary status because its perceived to be gamy and possibly unsafe. This perception is nearly unique to the United States; everywhere else, wild venison is coveted as a culinary delicacy. In part, this is because the United States is the only country where hunting wasnt historically restricted to the nobility or the landed gentry. During the Depression, game meat became sustenance for the impoverished, and anecdotal stories still abound of deer being poached to feed the family. Eight decades later, it is still largely coded as meat for the poor, even as it has been gaining popularity among middle-class locavores and slow food advocates as an organic, nutrient-rich, additive-free meat. For a small group at the very highest end of the economic spectrum, the opportunity to sample true game meat is a sought-after gastronomic experience.

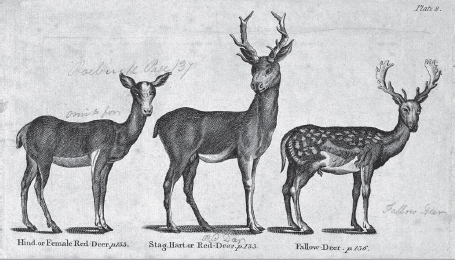

It is certainly true that venison can be gamy to the point of inedibility. It can also be delicious, but its precisely this unpredictability that distinguishes wild from farmed venison. Wild deer are highly varied in size and habitat, and each species requires different approaches in the kitchen. In the United States, the kinds of deer that can be legally hunted include the robust American whitetail, the blacktail, and the mule deer. In the United Kingdom, deer can refer to the small roe deer, the majestic red deer, the fallow deer, the Sika deer, the Chinese Water deer, and the Muntjaca miniature deer that regularly appears on lists of the Worlds Strangest Animals because it has fangs and barks like a dog. The red deer is the largest and most prestigious quarry, with the fallow deer a close second.

There are more kinds of deer than these nine, but they are among the most common species and subspecies that can be legally hunted in Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States. To be successful, game cooks must start by identifying the precise deer theyre handling. For example, the pale and delicate venison of the roe deer requires swift cooking and light sauces compared to the red deer. To handle roe deer as if it is red deer will result in dry and rubbery venison. However, the red deer is the more traditional quarry in Europe and the United Kingdom, making it what the old world culinary imagination casts as real venison. Much in the same way, in the United States, real venison defaults to whitetail. Thus, when Walt Disney made the animated American film Bambi , 1942, the title character was a whitetail deer. However, in the original European novel Bambi , 1923, the title character was a red deer. Disney made the change in order to avoid confusing American viewers, because there are no red deer in the United States. To American eyes, the red deer looked like a mutant. It was literally an alien species.

At the time, knowing the difference between a whitetail and a red deer was common knowledge, as there were many more hunters and cooks that would have prepared venison regularly. But matters changed quickly. Following the end of the Second World War, an extended period of prosperity meant that consumers no longer needed to know how to grow, fish, and hunt for food, let alone how to cook game meat so it tasted good. Seven decades later, only 6 percent of the American population still hunts, meaning that 94 percent of the general public has forgotten how to discern differences among deer species, which mush together into one big-eyed, black-nosed, long-legged symptom of natures bounty.

After Thomas Bewick, A hind and a stag of the family of Red-Deer and a Fallow-deer. Wood-engraving, 18th century. Credit: Wellcome Institute.

Bambis metamorphosis from red deer into white deer is just one example of a largely unnoticed cultural shift changing how we view wildlife. In this case, a new generation of diners is amazed by the fact that European aristocrats and American settlers used to choke down venison every night for supper. Was venison better in the good old days? Or have palates changed?

CONSIDER THE WHITETAIL

Because its geographically widespread across the North American continent and also easy to identify, the whitetail has become the iconic symbol of American wildlife. Like all members of the Cervidae family, the whitetail deer ( Odocoileus virginianus ) is a hooved herbivore. A male whitetail is a buck. A female is a doe. A juvenile is a fawn. Though it can graze (head down), it prefers to browse for food (head up), favoring berries, leafy bushes, and tree buds. Large bodied with slim legs, the adult whitetail ranges in size from 90-pound does to 300-pound bucks. Its pelt is brown with a white belly, and its most distinctive characteristic is the white underside of its tail, which it raises like a warning flag to alert other members of the herd. Fawns are reddish-brown and spotted. Mature bucks have pronged antlers, which they drop every year following the mating season, called the rut.