This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published in Great Britain in 2015 by Shire Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA.

E-mail:

www.shirebooks.co.uk

2015 Susannah Robin Parkin.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 803. ISBN-13: 978-0-74781-448-1

PDF e-book ISBN: 978-1-78442-082-6

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78442-081-9

Susannah Robin Parkin has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

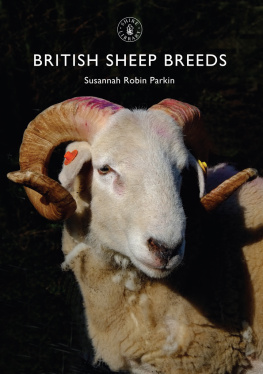

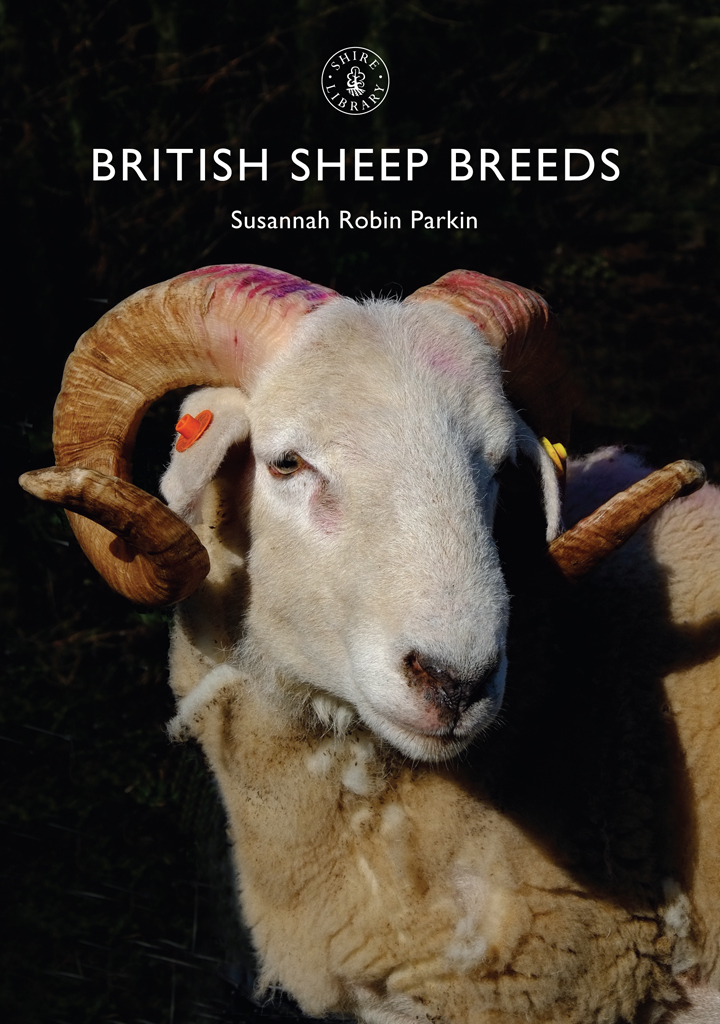

COVER IMAGE

Cover design and photography by Peter Ashley. Front cover: A Wiltshire Horn ram, Welland Colin, with grateful thanks to Mike Adams. The Wiltshire Horn is a very old native breed and, up until the end of the eighteenth century, was the principal breed to be found on the Wiltshire Downs. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, George III distributed Merino sheep throughout Wiltshire on the understanding that they would be crossed with the Wiltshire Horn. However, this was met with resistance from some local breeders and did not occur in all the native flocks. Eventually, this wool-less breed lost popularity in the latter part of the nineteenth century, owing to the contemporary emphasis on wool production.

TITLE PAGE IMAGE

A Romney ewe and her lamb.

CONTENTS PAGE IMAGE

Jacob lambs.

CONTENTS

THE HISTORY OF SHEEP AND SHEEP FARMING

BRITISH SHEEP THROUGH THE CENTURIES

ALTHOUGH IT APPEARS the dog was the first animal to be domesticated, it is thought that sheep followed the domestication process approximately two thousand years later. Domestication of sheep occurred around eleven thousand years ago and throughout history has played an integral role in British farming. Over the centuries sheep farming has faced many challenges, mainly owing to climate change and market demand. However, the evolution and adaptation of sheep breeds have ensured its survival.

Since prehistoric times sheep have provided mankind with fibre, pelts, meat and milk. This versatility combined with their behavioural characteristics is probably the major reason this species was so adaptable to domestication. Their origins can be traced to the wild Mouflon in Mesopotamia, a breed that is said to be the forebear of all sheep.

When the Romans first arrived in Britain in 55 BC, the sheep they found were a small primitive breed that had been introduced into Europe in the early Neolithic era (80006000 BC) these subsequently became confined mainly to the island of Soay (pronounced so-ay), from which the breed takes its name, and where the crofters traditionally made its fine wool into clothing. The Romans also brought their own long-woolled breed of sheep into Britain. Their sheep were small, hornless and white-faced, and their fleece was lustrous and wavy (crimp). It was these traits that the Britons favoured, so farmers cross-bred the Roman sheep with the indigenous Soay and the development of the early native breeds began.

There is little information about the arrival of sheep similar to the Soay between about 4000 BC and the eighteenth century AD. However, it is acknowledged that traders, raiders, invaders and voyagers transported sheep, and thus the distribution of domesticated sheep began. These travellers introduced the northern European short-tailed breeds such as Boreray, Castlemilk Moorit, Manx Loaghtan, North Ronaldsay and Shetland. Travellers from the south of Europe, the Romans, contributed to the ancestors of the English longwools and the Down breeds such as Dorset Down, Hampshire Down, Oxford Down, Cambridge Down, Shropshire and Suffolk. These breeds were introduced in the first century AD, initially by trading and then through invasion.

After the departure of the Romans in AD 410, the Vikings invaded Britain between the eighth and tenth centuries, bringing with them their own sheep. The Viking breeds developed into the Blackface, Swaledale and Herdwick and it is from these three groups of primitive strains that the diverse variety of British breeds originated.

From the twelfth century until the seventeenth, Britains textile industry flourished, sheep providing the wool for the cloth. During this period farmers had already started selective breeding to improve wool quality.

During the reign of Elizabeth I (15581603) the wool trade was the primary source of tax revenue and until the eighteenth century wool (rather than meat or milk) continued to provide the main source of income for the sheep farmer. It was the Industrial Revolution at the end of eighteenth century, accompanied by a population increase, which changed the course of sheep production. An era of high-production farming developed in which meat became the main commodity, milk and wool becoming by-products. Selective breeding became more widely practised and characteristics different from those desired in Roman times prevailed.

TEXTILES HAVE BEEN made by the tribes of northern Europe since 10,000 BC and, even before the arrival of the Romans and their sheep, Britain had a reputable wool industry. Great Britain became famous for textiles such as worsted, Scottish tweed and Axminster carpets. Many of the original British breeds had enormous influence, particularly in New Zealand, where the foundation flocks originated from Britain.

During the Middle Ages the Spaniards bred their native sheep with sheep from the East, which were further improved by cross breeding with the Roman sheep that were introduced during their invasion. The result was a superior fleeced Merino which was worth much more than the courser British fleece.

The history of the Merino is fascinating. During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries a powerful organisation known as the Spanish Mesta bred Merino sheep, which grazed on the southern plains in winter and the northern highlands in summer a system called transhumance. Merino wool, renowned to this day for its exceptionally high quality, was a very profitable commodity and the breeders gained many privileges from the kings of Castile. Furthermore, exportation of Merinos without royal permission was prohibited and was punishable by death, which safeguarded almost total dominance of the breed until the mid-eighteenth century. The British king, George III, an enthusiast farmer, was one of many sheep breeders who believed they could improve the wool still further by cross- breeding the Merino with indigenous breeds such as the Wiltshire Horn. In 1789, he managed to smuggle some Merino sheep into Britain, which grazed the grounds at Kew. It became increasingly difficult for the Spanish Crown to uphold the law, and eventually the export ban was lifted by the end of the eighteenth century Merino cross-breeding was at its height of popularity with British sheep breeders. Consequently, Merino bloodlines have been inherited by many native British breeds.