First published in 2009 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

David Scrivener 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 971 1

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mrs Joyce Tarren for allowing me to buy her late husband's collection of photographs, over 180 of which are reproduced in this book; and to Fred Hams and Andrew Sheppy for help with details of some breed histories.

Contents

Introduction

This is intended to be a companion volume to Rare Poultry Breeds, which should explain any apparent omissions or inconsistencies in the breeds covered. There are references to some rare breeds where they were involved in the development of popular breeds, mainly some now extinct American breeds, which had to be mentioned again in the histories of Plymouth Rocks, Rhode Island Reds and Wyandottes.

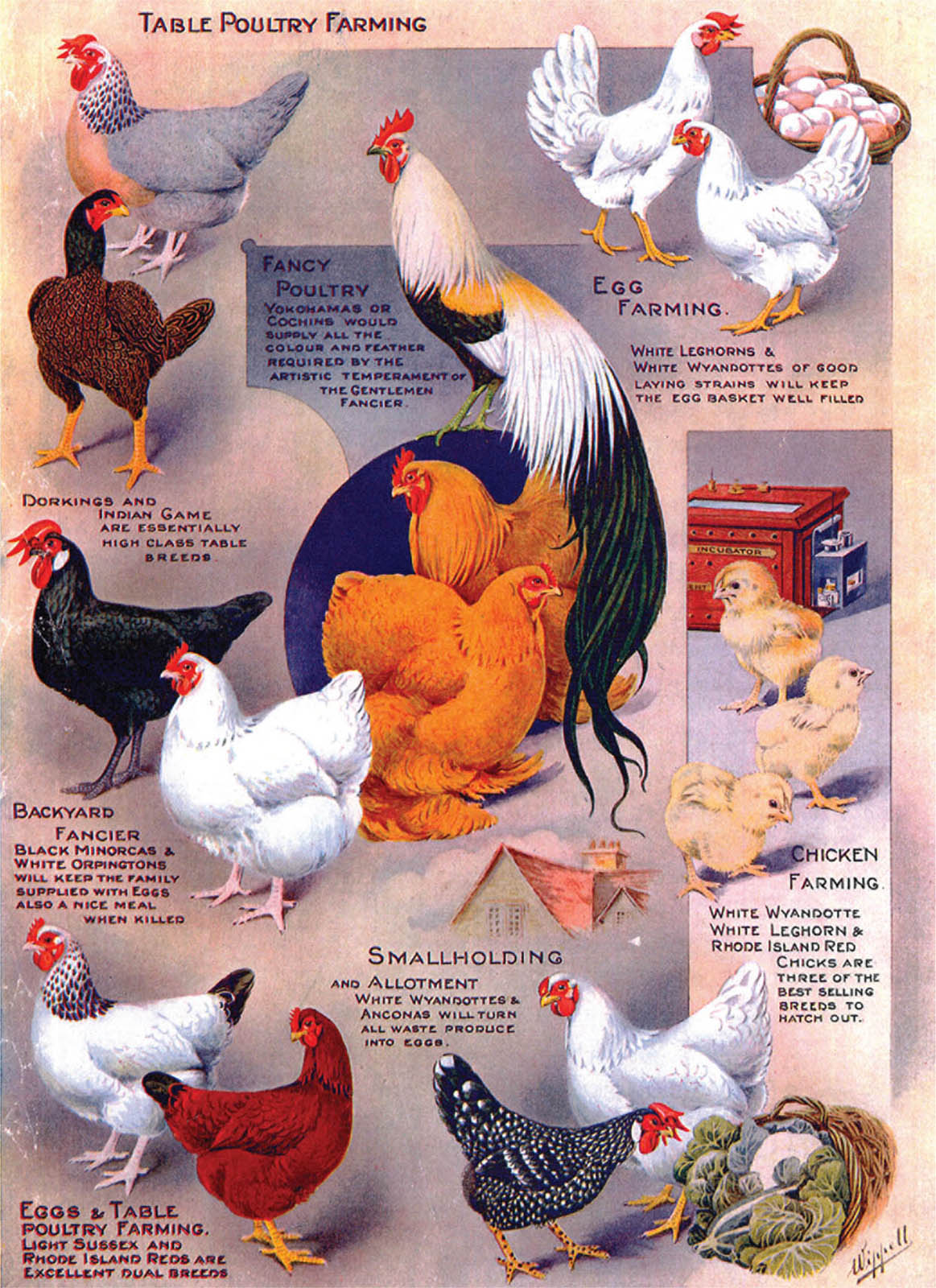

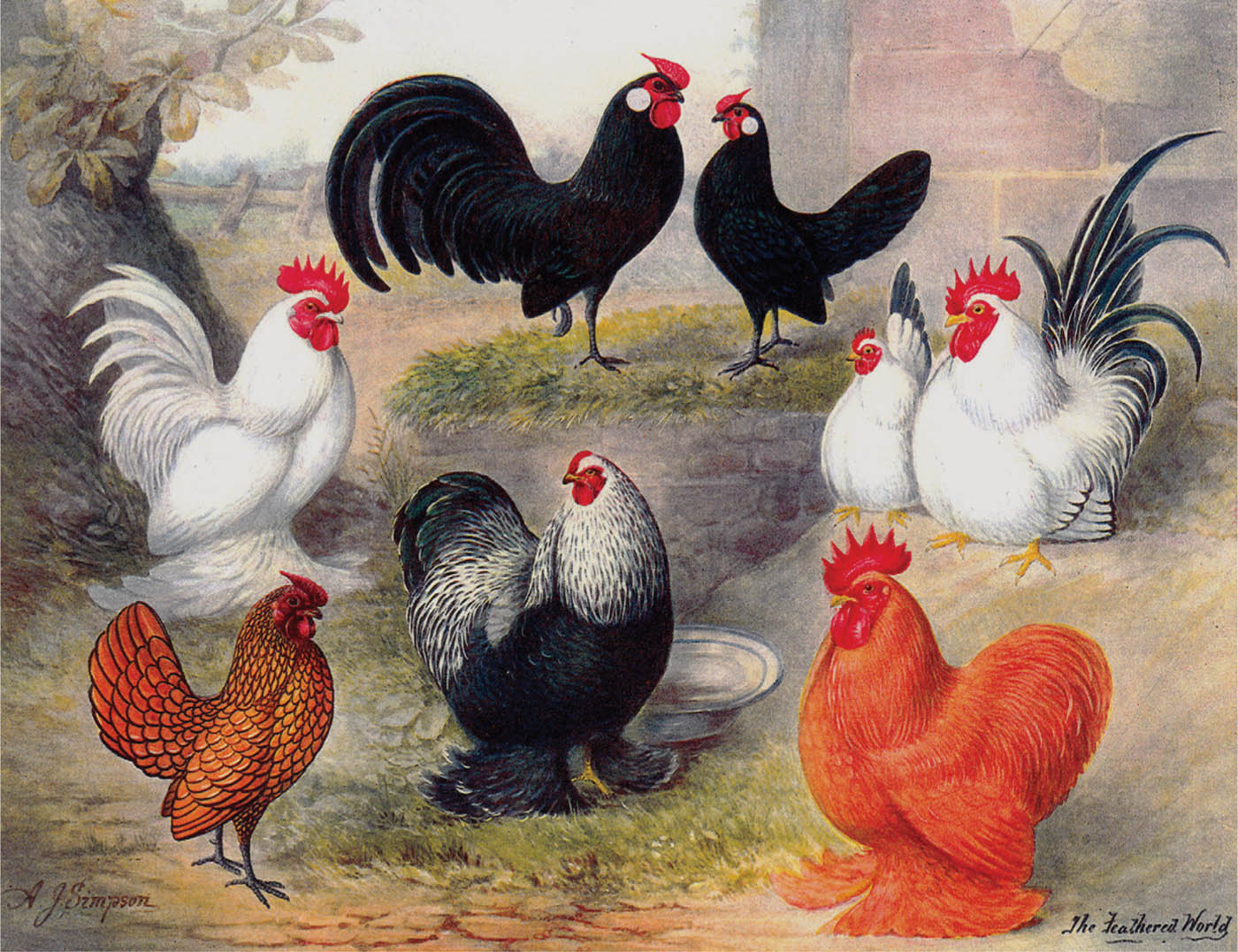

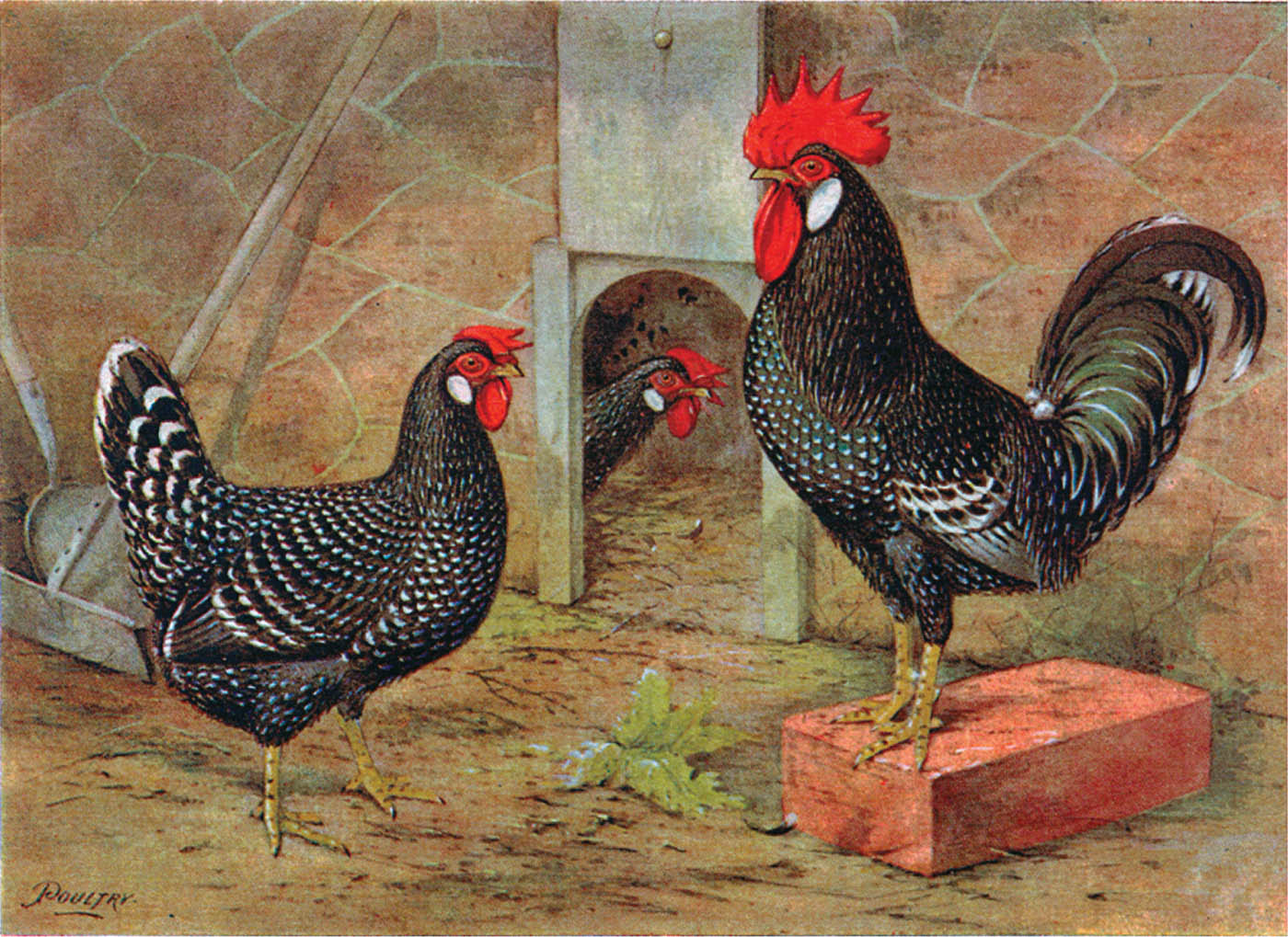

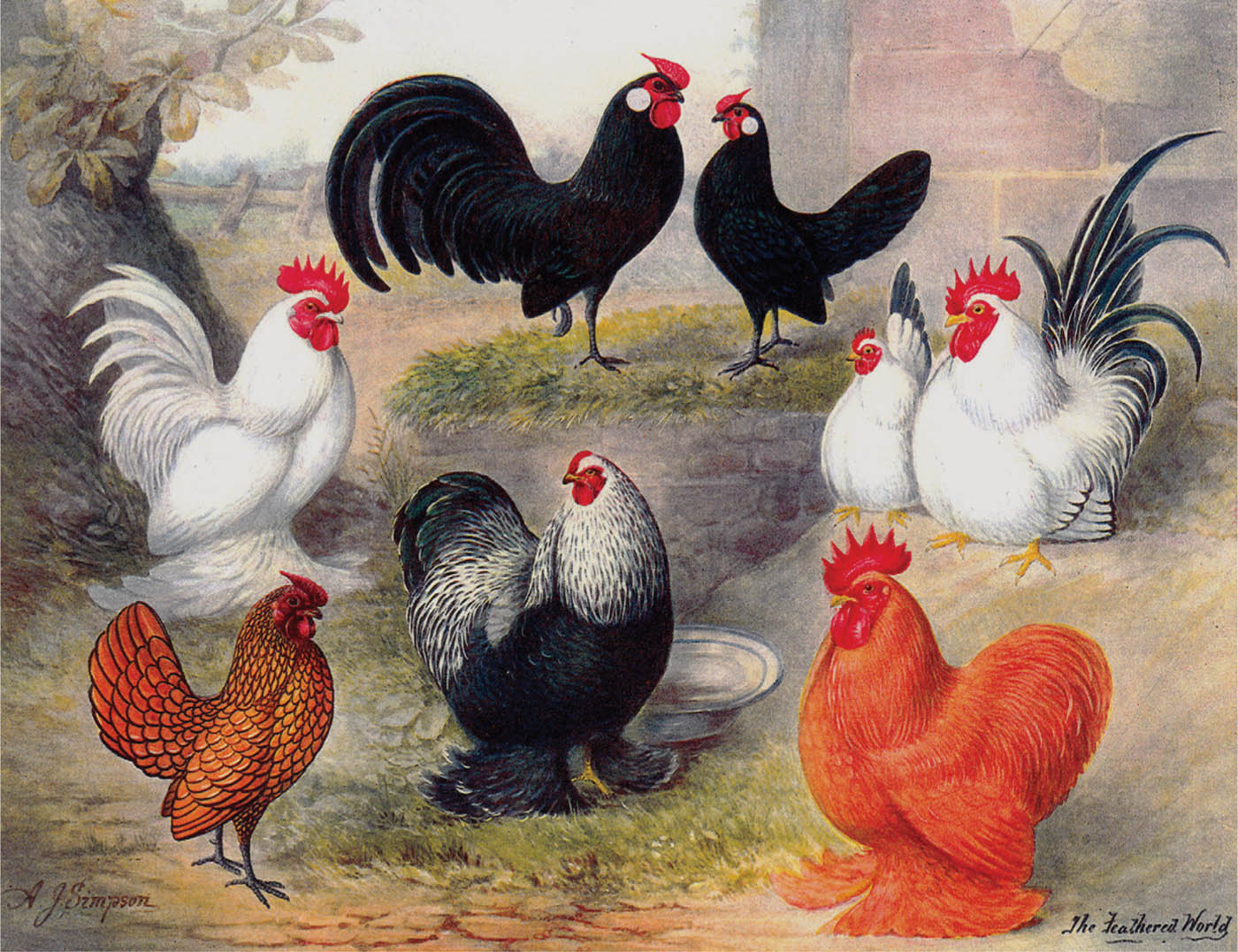

Bantams. Like many of the illustrations in this book, this picture comes from a print that was originally a free gift with a magazine, in this case Feathered World magazine, 2 March 1928. Artist: A.J. Simpson

Fortunately a lot of detailed information was documented, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, on the origins of the breeds covered in this book. In most cases it has been possible to give names and details of key individuals. In the case of some very ancient breeds, Dorkings for example, although their early history was never recorded, changes made to them in the Victorian era are known. Poultry shows, and the publication of detailed breed standards for show judges to go with them, stimulated most breeders to selectively breed for specific plumage patterns, comb shapes and so on, more than they had before.

In addition to the historical content, there are also some details of the main difficulties in breeding perfect specimens, and how to overcome them. Another of the authors books, Exhibition Poultry Keeping (also published by the Crowood Press) covers breeding and showing techniques, including double mating in much greater detail. It did not seem sensible to duplicate too much.

Most of the breeds included in Popular Poultry Breeds are also kept by many hundreds, in some cases thousands, of hobbyists all over the world. In some cases their breed standards are noticeably different from one country to another. These differences have been fully covered, and it is hoped that breeders in one country will be interested by the fact that their champion birds would not even be recognized by breeders and judges elsewhere.

CHAPTER 1

Ancona

Ancona is a city on the east coast of Italy, from which the first recorded shipments of chickens arrived in England in about 1850. Among the first importers and subsequent exhibitors were Mr Simons and Mr John Taylor. The latter, who lived at Cressy House, Shepherds Bush, London, was also a leading early breeder of Andalusians. For most of the century-and-a-half since then, Anconas have been universally recognized as a single plumage colour breed, black with small white tipping. This was not the case in the first few decades of the changes from simply being local laying hens to being an internationally recognized proper breed. Readers should be aware that in the 1850s, although some birds had already been taken from the west-coast port of Livorno to the USA, the Leghorn breed had not yet been properly established. In addition to the expected ancestors of the present Ancona breed (birds with variations of black-and-white mottling from neat spotting to random markings like the later Exchequer Leghorns), there were also Black-Red/Partridge and Cuckoo barred Anconas. The then local name for black-and-white plumaged birds was Marchegiana, the name of a nearby district. However, even these varied, some coloured as Spangled OEG or a white-spotted variation of Duckwing Game.

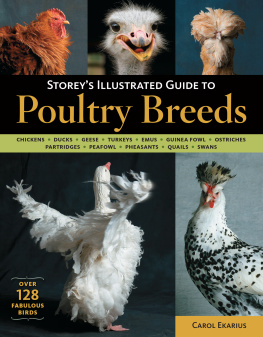

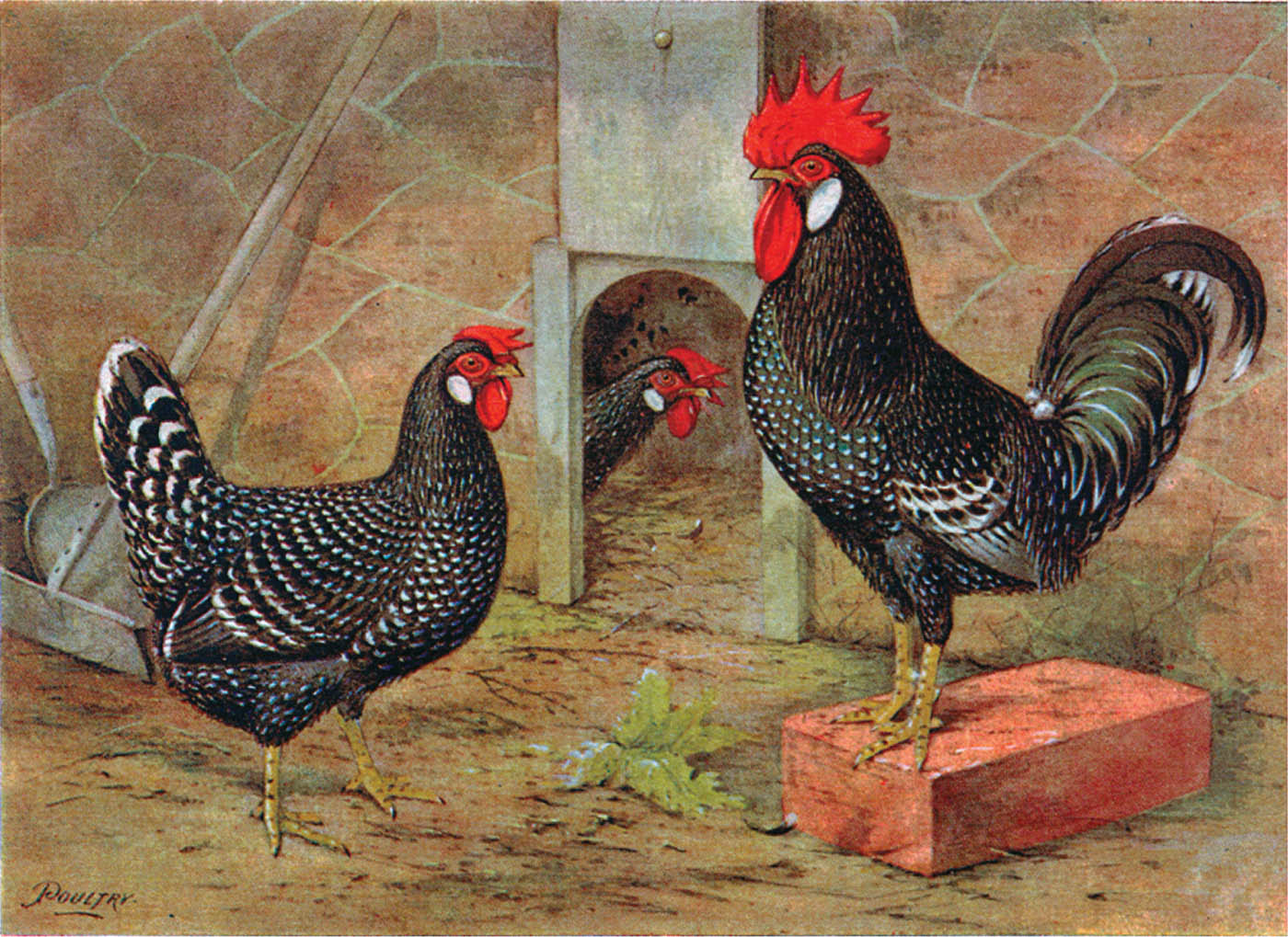

Anconas. Originally a free gift with Poultry magazine, circa 1912. Artist: J.W. Ludlow

Although they were good layers, their varied appearance led many authorities in the world of poultry keepers to write them off as mongrels for many years. This attitude started to change when Mr A.W. Geffcken of Southampton obtained a fresh importation of more uniformly coloured Anconas in 1886. These were all black with white spots, although the white markings were not yet as neat and tidy as they would become. They also had the present shank/foot colour of yellow with black spots. Over the following decade Mr Geffcken, and subsequently his customers, spread them around the country. Mrs Constance Bourley of Frankley Rectory near Birmingham was a particularly enthusiastic Ancona breeder of this period, who was quoted in the livestock Journal Almanack of 1895 and in Wrights Book of Poultry praising their hardiness, activity and laying ability on her wet, windswept hilltop farm. She said most other breeds she had tried had sickened and died there, with the survivors laying very few eggs. In contrast, Anconas kept themselves warm by foraging around the fields, even when there was snow on the ground. No doubt she would have been one of the founder members when the Ancona Club was formed in 1898. Some Ancona Club members concentrated on tidying up their plumage markings, in response to the very generous show prize money and high sale prices of potential winners then. However, Ancona Club members were aware of the dangers of separate exhibition and utility types developing, as happened with some other breeds. The Club agreed a joint breed standard with the National Utility Poultry Society in 1926 to avoid this.

Mrs Bourleys praises of Anconas as active layers in free range conditions were confirmed by hundreds of other small scale poultry keepers through to the 1950s, but they were also rather wild and nervous. These were valuable survival instincts in free range flocks, which could get safely up a tree when foxes were on the prowl, but less welcome with larger scale commercial egg producers. Several such producers gave up Anconas during the 1920s because they could not be tamed when kept in laying flocks of 100 to 1000 in deep litter houses, with or without outside runs (normal commercial conditions then), without birds being lost by panicking. A Mr Messenger reported in 1921 that fifteen glass windows were smashed by a flock of 150 Anconas over a three-week period, despite their attendant being a quiet and elderly man with a lifetime of chicken-keeping experience.

Most Anconas have always been single-combed, but a rose-combed variety was bred by crossing with Hamburghs and Wyandottes, the latter type predominating. These first appeared about 19025. Eventually, say by 1930, the only difference was the comb; but up to about 1920 rose-combed Anconas were noticeably heavier and more docile than single-combed Anconas. They were made to cope with cold climates, as large single-combed chickens can suffer from frostbite. There was a separate Rosecomb Ancona Club in the UK, 192326.