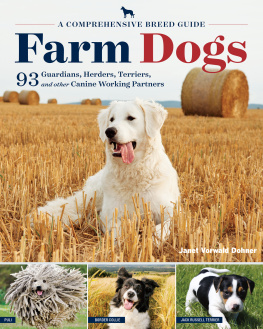

Purebred animals predictably reproduce their breed type, both in appearance and performance, when mated with one another. This predictability of appearance, ability, and function through generations is the essential key to the importance of breeds, because predictability is what allows successive farmers and ranchers to consistently achieve their specific goal in a selected setting.

That setting is the other key principle. A Jersey dairy cow is a good choice for producing rich milk on a dairy farm in a temperate climate, while a Texas Longhorn is a good choice for meat production in a drier region. Your farming goals will be met best when the breed matches the setting.

Goals for raising livestock vary widely and can include almost as many options as there are farmers. This list shows some objectives common to different regions and species, but it is only a sketch of the many opportunities possible.

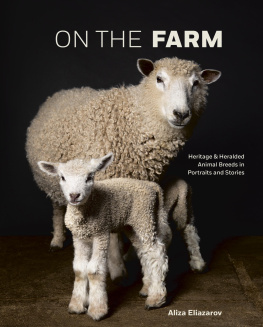

The Origins of Breeds

The fascinating history of heritage breeds goes back at least ten thousand years, to the handful of small areas of the globe where agriculture began and the earliest farmers first domesticated the now-familiar species of farm animals. As human populations grew, farmers spread out into diverse climates and terrains, bringing along their domestic livestock, which provided essential food, power, and fertilizing manure.

The resources of these early farmers were usually limited even hay was a luxury for many. As a matter of necessity, owners quickly learned to keep and breed only those individual animals that thrived and provided a good return for the farmers (often minimal) investment of feed, shelter, and labor. Characterized by limited resources, these farming systems produced breeds of animals that are still productive today as well as uniquely adapted to local conditions, a key feature of heritage breeds.

Breeds Grow from Community

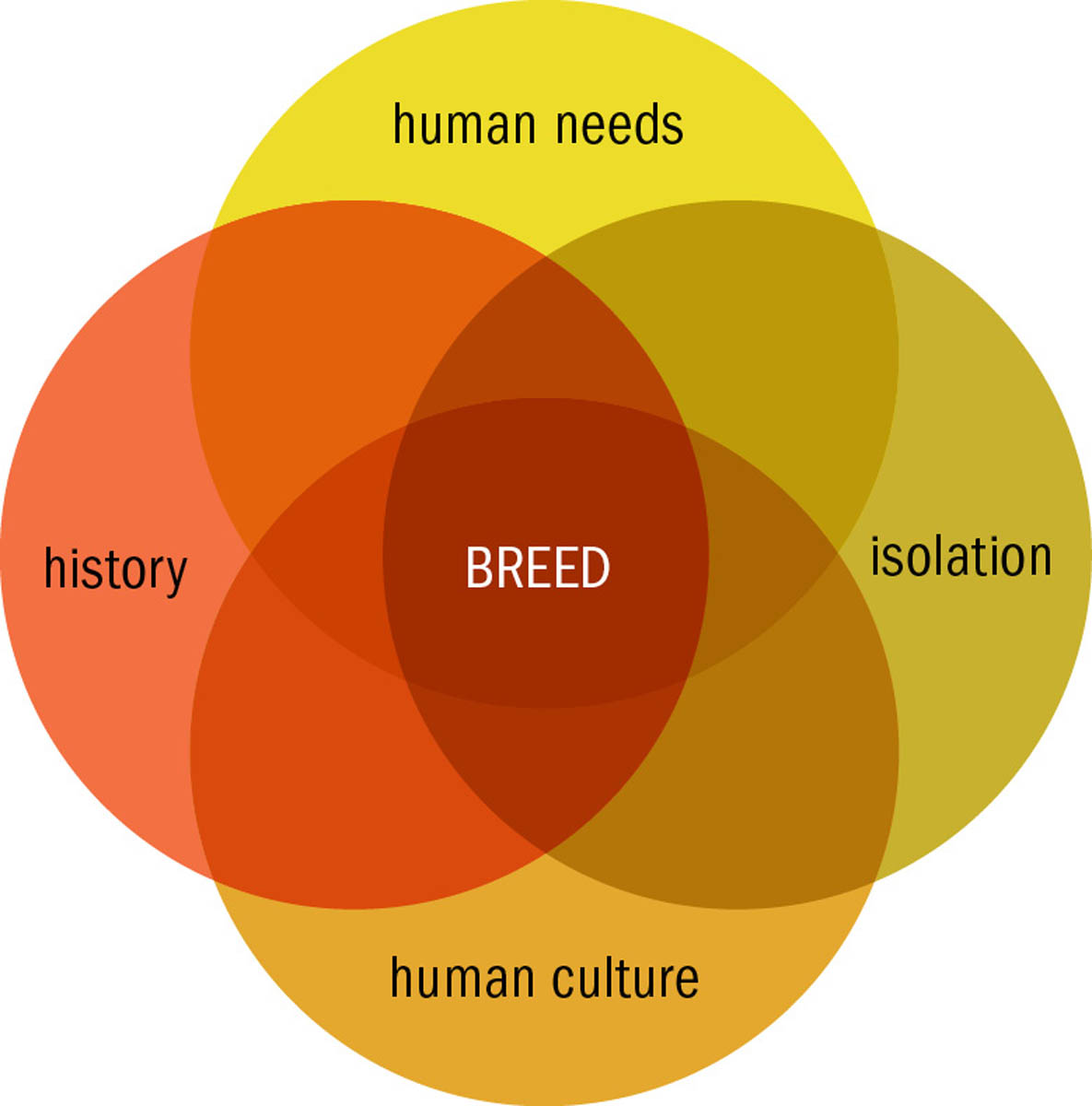

Breed development is an intricate story of the strong and specific connections among animals, land, culture, and the needs of the people who use them. Each time a group of farmers migrated to a new environment, they chose breeding animals for their abilities both to survive and to produce. Every new settlement began with a different set of founding animals, and each had its own combination of climate challenges, terrain issues, and human demands. Each combination of environment, original animal genetics, and human selection produced its own final genetic packages: that is, its own heritage breeds.

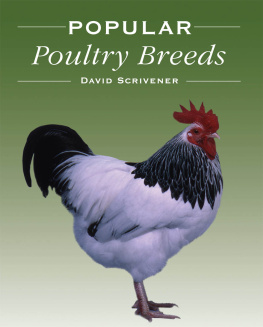

The result? Over the entire globe, human communities in a wide variety of environments tested, molded, and perfected thousands of breeds of chickens, goats, sheep, cattle, horses, and other traditional farm animals. This long history of partnership between animals and people often goes even deeper: many heritage breeds also reflect the cultural approaches to survival of various ethnic groups, specifically the different ways in which each group adapted to and used its environment.

Breeds are influenced by several cultural factors.

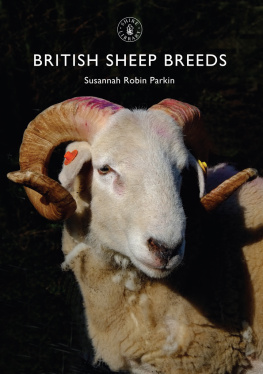

Breeds Reflect Their Environment and Their Owners Needs

Navajo-Churro sheep are survivors. Descended from sheep brought to the New World centuries ago by the Spanish conquistadors, the breed was founded on those few individual sheep that were able to thrive in the harsh desert environment where few other sheep would even survive. Through the generations, the sheeps Navajo and Hispanic herders selected the hardiest, most productive animals for breeding to create todays resilient and productive Navajo-Churro breed. In return, the sheep have faithfully served their owners for several centuries by producing wool and meat. They also came to occupy an important place in Navajo culture and unique roles in Navajo ceremonies.

The distinctive wool has a long outer layer of coarse strong fibers and a softer, short inner layer of very fine fibers. Local Navajo and Hispanic spinners and weavers use it to produce intricate and beautiful rugs that are significant cultural expressions of the two communities most connected with the sheeps history and use. Demand for this unique wool makes the breed important to the health of the local economy and now assures the breeds survival into the future.

The final success or failure of breed survival often depends on animals living on real farms managed by real farmers, who need an economic return from their animals in order to make a living. Successful farmers make for successful breed conservation.

Terms to Know

Genetic diversity. Variation within a breed. Some diversity is obvious, such as color. Less visible traits include disease resistance, foraging ability, and agreeable behavior.

Uniformity. Lack of variation within a breed. Holsteins are fairly uniform for high levels of fluid milk production, and Texas Longhorns for survival in arid regions. On the positive side, farmers can accurately predict performance. The negative side emerges if goals change or the environment changes, because uniform populations may not have the genetic code for adaptation to new challenges.