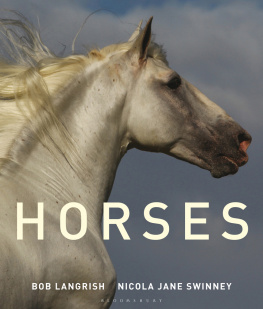

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Copyright 2014 in text: Nicola Jane Swinney

Copyright 2014 in photographs: Bob Langrish

Copyright 2014 Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The rights of Nicola Jane Swinney and Bob Langrish to be identified as the author and photographer of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

ISBN 978-1-4729-1083-7

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown in managed sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable. The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulation of the country of origin.

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here.

Note on measurements

Imperial measurements are traditionally used in the equestrian world, with races, for example, always being expressed in miles, yards and furlongs. Horses are traditionally measured as hands high (hh) at the shoulder, with a hand being 4 inches.

Introduction

In his iconic poem In Praise of the Horse, Ronald Duncan says about the horse that All our history is his industry. The phrase perfectly sums up our eternal relationship with equines; throughout human history, worldwide, the horse has been there with us at work, at war and at leisure. While the dog is universally known as mans best friend, perhaps the horse better deserves this epithet. This book profiles more than 70 of the worlds horse breeds, describing their history, development, characteristics and relationship with humans.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE HORSE

It is now widely accepted that the first ancestor of todays horse, Equus, was Hyracotherium, also known as Eohippus, or Dawn Horse. Dating back to the Eocene epoch 5634 million years ago, this creature bore little resemblance to the modern equine. Living in the forests of North America, it was somewhat doglike, with a short neck, arched back, short legs and long tail. It had four toes on each front foot and three behind, and walked on pads like a dog.

Hyracotherium was a grazer living on fruits and soft foliage, and was a successful forest dweller, changing little for around 20 million years. Then the climate of North America changed, becoming drier. The vast tracts of forest shrank and grasses evolved. Hyracotherium grew taller and leggier so that it could run faster in the open, where it was at its most vulnerable, and its teeth became tougher to enable it to grind down grasses. At this stage it became known as Mesohippus.

It should be noted that the evolution from Hyracothium to the modern Equus is not a progression along a neat straight line, even though it is often depicted as such. Rather, Equus is but a branch of the evolutionary tree. For example, after Mesohippus came Miohippus, a change that occurred quite suddenly in evolutionary terms. Miohippus was larger than its older cousin, with a longer skull, its ankle joints altered and its teeth changed. Fossil evidence shows that these two animals overlapped, rather than Mesohippus gradually morphing into Miohippus.

Later transformations saw the horse begin to walk on tiptoe, using its middle toe rather than its pads to enable it to run fast; its leg bones fused and its musculature strengthened to make it a swift runner. Around 17 million years ago came Merychippus the horse with a new look. Standing at around 10hh (or 40 inches high) and as such being the tallest equid yet, Merychippus was the first animal to closely resemble the modern Equus.

Merychippus underwent rapid transformation and is thought to have developed up to 19 different strains, separated into three groups: three-toed grazers known as hipparions, a line of small horses known as protohippines and a line of true equines. This last was a large horse-type species with small side toes, and it gave rise to at least two separate groups. Both groups lost their side toes and developed side ligaments around the fetlock that helped to stabilize the central toe, enabling them to move at speed.

The one-toed horses included Pliohippus, which until recently was thought to be a direct ancestor of Equus. However, differences in its skull formation and its teeth prove otherwise, although they were obviously related. The second group is Astrohippus, which is considered to be a descendant of Pliohippus. There is a third, recently discovered strain called Dinohippus, around 12 million years old, which bore a compelling resemblance to Equus, although its exact ancestor is unknown. Dinohippus was the most common strain in North America.

Ten million years ago there was an explosion of diversity within the horse family, both in types and in numbers, which has never since been equalled. Our horse, of the genus Equus, developed around four million years ago, and the three-toed hipparion died out altogether. Until about a million years ago, there were Equus horses in vast migrating herds all over Africa, Asia, Europe, and North and South America, but as the Ice Age began the horses of the Americas died out, although the cause of this extinction is unknown.

MODERN HORSES

Przewalskis Horse, discovered in the 19th century, is our closest link with primitive equines. It has the so-called primitive features of black points, upright mane and dorsal stripe down its back.

The modern horse, a subspecies of the genus Equus (Equus ferus caballus) and a member of the family Equidae, is a perissodactyl a hoofed mammal that bears its weight on its middle toe. Other perissodactyls are the tapir and rhinoceros.

Although there are no longer the numbers or the enormous herds of wild horses that there once were, the sheer diversity of type and breed is astonishing. is an Equus subspecies (E. f. przewalskii). It is our one remaining link to the primitive equines that roamed the vast tracts of Asia, yet its origins remain a mystery. It is almost as far from the beautiful Arab as two members of the same genus can possibly be. The huge Forest Horse of Europe, also known as the Diluvial Horse, is no more. However, its echo can be seen in the mighty Shire, the worlds biggest equine breed. The tiny Shetland of Scotland and the sturdy Exmoor, Britains feral pony, portray the primitive traits of the ancient Equus, while the Americas, which lost their indigenous horses thousands of years ago, now have an equine cornucopia.