SARAH A. CORBET, ScD

PROF. Richard West, ScD, Frs, Fgs

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT

PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

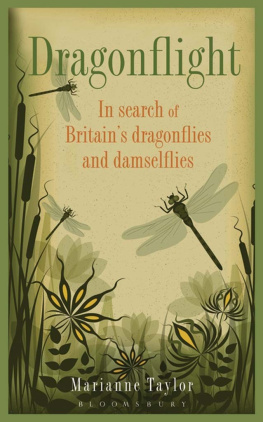

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

Dedicated with affection and gratitude to Sarah Jewell and Ann Brooks

DRAGONFLY

Now lets have another try

To love the giant dragonfly.

Stand beside the peaceful water.

Next thing a whispy, dry clatter

And he whizzes to a dead stop

In mid-air, and his eyes pop.

Snakey stripes, a snakey fright!

Does he sting? Does he bite?

Suddenly hes gone. Suddenly back. A

Scarey jumping cracker

Here! Right here!

An inch from your ear!

Sizzling in the air

And giving you a stare

Out of the huge cockpit of his eyes-!

Now say: What a lovely surprise!

Ted Hughes

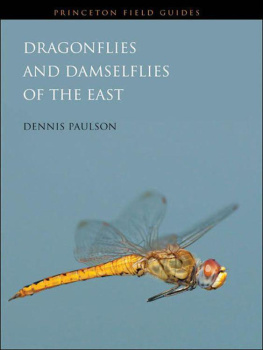

FRONTISPIECE. Sequential digital still photography is a wonderful tool for tracking this male Orthetrum cancellatum as he flies by. The technique can be used to reveal the natural attitude of the wings, abdomen, head and legs while a dragonfly is in flight (Steve Cham).

D RAGONFLIES ARE OF particular interest to naturalists because they are lively, beautiful and interesting, and amenable to study without expensive equipment or laboratory facilities. Furthermore, well illustrated field guides make it relatively easy to recognise the British species. An earlier New Naturalist, published in 1960, did much to bring the interest of dragonfly biology to the attention of naturalists, and to stimulate further research. Since then, dragonflies have become popular among both amateur naturalists and research workers; they have been transformed from an enigmatic group of minority interest to a focus of enthusiastic amateur study and exciting research on diverse aspects of ecology, behaviour and physiology. We now understand much more about what they do, and how and why they do it; so they deserve this completely new New Naturalist. Both of the authors have made major contributions to the study of British dragonflies, and have done much to encourage naturalists to appreciate them. Their book, illustrated with Robert Thompsons magnificent photographs, will enrich the study of dragonflies by the many naturalists who are already committed to this group, and will surely encourage new recruits to take up that interest.

P HILIP CORBET WAS without doubt the worlds foremost odonatologist and one who has had the greatest influence in the burgeoning interest in dragonflies for the past 50 years. With his Reading B.Sc dissertation and Cambridge Ph.D thesis he made the first strides in a monumental research career involving dragonflies.

His varied and distinguished appointments included research positions with the East African High Commission in Uganda; Director to the Research Institute, Canada Department of Agriculture; Professorships with the Universities of Waterloo (Canada) and Canterbury (NZ); Commonwealth Visiting Professor (University of Cambridge); and Professor, University of Dundee from which he retired in 1990 as Professor Emeritus.

Corbets research interests emphasised periodicity, rhythmic behaviour and development in dragonflies and mosquitoes. These have been the co-ordinating strands in studies relating to taxonomy, morphology, life histories, arthropod-borne virus diseases, reproductive physiology, ecology of fishes and crocodiles, and arctic microclimates.

After retirement in 1990 he concentrated on the production of two major books: Dragonflies: Behaviour and Ecology of Odonata, published in 1999 is a definitive synthesis for which he was awarded the Neill Medal for Natural History by the Royal Society of Edinburgh. This masterly volume appeared in Japanese translation in 2006. This fine current New Naturalist with Steve Brooks is a fitting closure to an extraordinary career.

Philip Corbets numerous awards include four higher doctorates: the Gold Medal for Outstanding Achievement from the Entomological Society of Canada, election to Fellowships of three prestigious societies, Honorary memberships to three national dragonfly societies; and he was elected to the Presidency of the Worldwide Dragonfly Association 2001-2003.

Michael J. Parr

Inaugural President,

Worldwide Dragonfly Association.

1998-2001

F EW INSECT GROUPS command more awe or are more immediately recognisable to so many people as the dragonflies. They are a source of beauty and inspiration to all who take time to watch them. Their aerial skills and finely honed hunting abilities on the wing are second to none, yet these creatures retain many attributes that first evolved in recognisable ancestors more than 300 million years ago. Dragonflies tell us a great deal about what insects were like before the origin of flexing wings or complete metamorphosis, characters that foreshadowed the vast number of higher insect species. Dragonflies are superb animals for the study of countless aspects of biology. Their aquatic larvae are important components of freshwater ecosystems and are indicators of water quality. Their territoriality and hunting skills make them excellent subjects for learning about animal behaviour. Their large size permits a much broader range of observations in the field than is possible for most other kinds of insects. Making these spectacular animals accessible to a wider audience is a worthy goal, and one fulfilled admirably by this volume.

There are no contemporary natural historians whom I admire more than Philip Corbet and Steve Brooks, nor any who are in a better position to have prepared this book. We are truly fortunate that they have combined their unmatched knowledge, experience and observational and writing skills to pull together such a wealth of material on British odonates. The book provides a wonderful foundation for anyone discovering the study of odonates for the first time or seeking to expand their knowledge by better understanding the breadth of dragonfly biology. The range of subject matter in this book is impressive, covering such diverse topics as habitats, populations, life history, parasitoids, feeding behaviour, seasonality, flight, sexual behaviour and maturation. This provides a firm foundation for in-depth studies of dragonflies in general and the British fauna in particular.

With this background and the authors sound advice on how to locate, collect, photograph and identify British dragonflies, a spectacular world is opened to the interested observer. This constitutes one of the best introductions to odonatology available and will, I predict, contribute to the widening interest in dragonflies in Britain and the education of a new generation of both professional and amateur odonatologists who delight in the study of these most fascinating of creatures. As our environments continue to change rapidly in the decades ahead, a growing awareness and understanding of our dragonflies will prove essential to science and biological conservation. No one who would truly understand either insect evolution or the function of ecosystems associated with fresh waters can do so by ignoring the Odonata. The growth of expertise on any taxon depends heavily on access to reliable and inspiring literature; the dragonflies will profit immensely from just such a contribution from Corbet and Brooks.