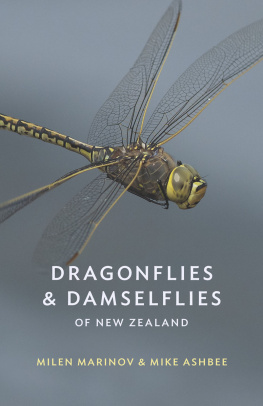

W hat came first, our invention of the dragon, or our discovery of the dragonfly? The concept of a dazzling jewelled creature borne on shining wings, as ferocious as it is beautiful, fits the real insect just as well as it does the mythical beast, if we ignore the small matter of scale. Gram for gram, a dragonfly packs a mighty predatorial punch a powerful and incredibly agile flyer, with colossal eyes that cannot miss the smallest movement, long barbed legs for snatching prey, and (especially in its infancy) an eating apparatus so bizarre that it has inspired some of our most horrifying fictional monsters.

Dragonflies are considered primitive insects from an evolutionary point of view. Unlike butterflies, bees and beetles, they do not pass through a pupa stage on their way to adulthood, but the adult dragonfly just bursts straight out of the skin of the full-grown larva, or nymph as the aquatic young is sometimes known. When the time comes for adult dragonflies to reproduce, they join together and mate via an extraordinarily circuitous process that is unique in the animal world.

Legends frequently link fire-breathing dragons and distressed human damsels, and so it is with their insect namesakes too. The insect order Odonata contains the dragonflies and a similar number of their small relatives, the damselflies. Like dragonflies, damselflies have long, slim bodies and two pairs of filmy wings, but they are lightly built, fragile-looking, graceful creatures. This delicate appearance belies their nature, for the damselflies are also skilled hunters of smaller insects, although they themselves may fall prey to the bigger dragonflies.

Unlike the dragon of legend, which is born into fire, the dragonfly starts its life in water, and its life as a nymph underwater is usually many times longer than its existence as a flying adult will be. Although a big adult dragonfly has the potential to cover hundreds of miles on the wing, it still needs to find fresh water to breed. Therefore, dragonflies are most often seen hunting around or close to water, whether that is a lake, river, heathland ditch, moorland tarn or garden pond. Damselflies, which fly more weakly, rarely stray far from the edge of the water where they spent their infancy. If you want to see plenty of dragonflies and damselflies, wait until spring and head for a watery landscape.

About 40 species of dragonflies and damselflies regularly breed in the UK. New potential colonists appear from time to time, making it difficult to be more precise about this figure, and there have been extinctions of several Odonata species over the last 50 years. Some of our resident dragons and damsels are common and widespread go anywhere where there is fresh water at the right time of year and you are likely to see them. Others are scarce and restricted to just one or a few patches of habitat, so a special trip will be needed. To see the vagrant dragonflies that periodically wander here from overseas, you really just need to be very lucky (and be able to get time off work at very short notice).

Though I have been an ardent nature-lover all my life, my passion for dragonflies and damselflies has been a slow-burner. However, two separate experiences stand out as pivotal in my growing appreciation of them.

A FALLEN DRAGON

The summer of 1995 was glorious week after week of beautiful weather. I remember it better than the others of the 1990s because it was the year I graduated from Sheffield University, and my boyfriend of the time and I spent most of it travelling around the UK in a camper van, looking for butterflies. In between these trips, we stayed with our parents more often with Jamess than mine as his mum and dad had a country house, surrounded by dipping and diving Sussex hillsides, and there was no better way to pass a sunny afternoon than out on their patio, contemplating the stunning view while nursing a cold drink.

We had brought two rescued cats with us from Sheffield. Often, our silver tabby would keep company with us on the patio, and do her best to catch the big dragonflies that were themselves out hunting over the garden, chasing down smaller flying insects. She was a young and athletic cat, and made prodigious leaps at the dragons as they rattled past, but didnt really look close to catching one.

I couldnt tell you now which species these dragons were. I knew they were hawkers, or aeshnas according to the rather quaint terminology of my Readers Digest insect book, because they were very big, never seemed to settle, and wore beads of bright green and blue colour in neat symmetrical patterns down their long, parallel-edged black bodies. They had fighter-jet speed coupled with the agility of a hummingbird, and while you could never hope to touch one in flight they would zoom past your ear with millimetres to spare, the dry hard rattle of the fast-flickering wings making you jump out of your skin if you hadnt seen them coming. Although my interest then was in birds and butterflies, it was impossible not to notice and admire these spectacular dragons.

One day, the cat managed a particularly high and well-timed jump, and somehow brought down one of the hawkers, which she immediately tried to subdue with a bite. James rushed forward, grabbed the cat, and eased the struggling insect clear of fangs and claws. I shut the thwarted cat inside and hurried back out, where James was opening his hand to reveal a very sorry-looking dragon.

Bashed and bitten, its wings were crumpled and its dented body had lost its glittering colour. It was still alive though, its skinny stick-legs supporting most of its weight, and it hung on hard to Jamess hand with six wicked-looking claws. Id never had the chance to look at a dragonfly close-up before, and I was immediately fascinated. I was used to looking at butterflies at point-blank range, but this was something else. While a butterflys coating of fluff softens its features and makes it almost mammal-like, almost cuddly, here the details of the creatures structure were laid bare. It seemed assembled from a great toy box of finely machined parts, individually painted and precision-cut to fit together. From its immense wrap-around eyes to the tidy successive sections of its long, slim body, it was extraordinarily beautiful and utterly alien.

As we examined it, we both noticed at the same moment that something strange was going on. Before our eyes the damaged wings were slowly straightening and stiffening, and the squashed part of its abdomen was puffing up to its correct dimensions. Colour was returning to its body and eyes, and it was standing straighter, its abdomen lifting clear of Jamess fingers. The head suddenly tilted, making us both jump was the dragon looking back at us? The restored wings began to vibrate, blurring away the exquisite tracery of vein-work, and then the dragon lifted off straight up like a jump jet. It flew powerfully away, hardly a trace of a wobble to betray its recent brush with death.

THE ORIGIN OF BEAUTY

I began to notice dragonflies more after that. However, it wasnt until the following year that their smaller cousins, the damselflies, really pushed their way into my consciousness. James and I had moved to a place of our own, in the village of Groombridge in Kent and also in East Sussex. The pretty river Grom bisects the village and marks the county border. We lived in the Sussex half. Several mornings a week I would get up at dawn to patrol my patch a piece of mellow Wealden countryside at once both anonymous and gorgeous and document the birds and (at the right time of year) butterflies I saw in the fields and woods.

Next page